Scientists Narrow Search for the 'God Particle'

Scientists are inching closer to a glimpse of the theorized 'God particle' — the mother of all particles — researchers from Fermilab announced today at the International Conference on High Energy Physics (ICHEP) in Paris.

The work is part of the quest to discover the Higgs boson particle, theorized to give mass to all other particles and hopefully answer questions about the makeup of the universe. Scientists at Fermilab have significantly narrowed the possible sizes, or the mass range, of the Higgs boson particle, trimming the possibilities by a quarter.

Searches by previous experiments and constraints due to the Standard Model of Particles and Forces, the theory that explains why particles have mass, indicate that the Higgs particle should have a mass between 114 and 185 GeV/c2 (GeV/c2 is a measure of mass and stands for gigaelectronvolts divided by the speed of light squared — 100 GeV/c2 is equivalent to 107 times the mass of a proton).

The Fermilab experiments now exclude a Higgs particle with a mass between 158 and 175 GeV/c2.

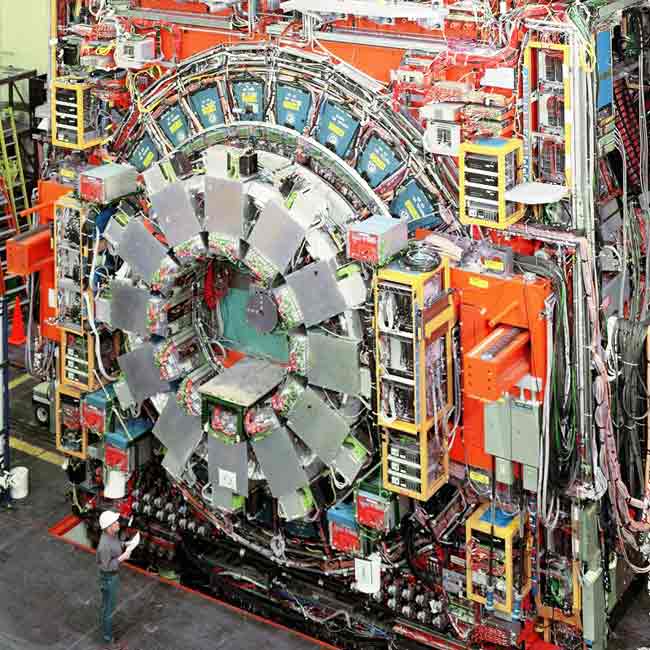

The work is the result of more than 500,000 billion collisions between protons and antiprotons — building blocks of larger molecules — that the researchers have studied since 2001. The collisions took place in Fermilab's Tevatron collider, which shoots two beams of particles around a 3.90-mile (6.28-kilometer) circle in opposite directions until they smash into each other, spewing out loads of energy and hopefully some new and exciting particles.

"Our latest result is based on about twice as much data as a year and a half ago," said Stefan Soeldner-Rembold of the University of Manchester in England. "As we continue to collect and analyze data, the experiments will either exclude the Standard Model Higgs boson in the entire allowed mass range or we'll go on to see first hints of its existence.

"There is less and less room for the Higgs boson to hide now."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These data, along with the work at the mother of all atom smashers, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), help scientists narrow the window on where to look for the Higgs boson. Data from the first three months of LHC's operation was also announced at the conference.

"There are important pieces missing in our understanding of the basic building blocks of the universe, and these results are an important step in learning how our universe works and why it exists," said John Womersley of the Science and Technology Facilities Council in England, which funded the work.

The Higgs boson particle was originally proposed by British theoretical physicist Professor Peter Higgs as a solution to one of the most basic puzzles in particle physics — why some particles possess mass and others do not. Since then scientists could only speculate about the existence of the Higgs particle, but thanks to current research and experiments being carried out at the LHC at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Switzerland and the Tevatron Collider at Fermilab near Chicago, a glimpse of the Higgs boson particle could soon be a closer reality.

Despite having the biggest atom smasher ever built, some scientists want to go even bigger. To better simulate the moments after the Big Bang, the theorized creation of the universe nearly 14 billion years ago, scientists are proposing a $12.85 billion, 31-mile (50-km) tunnel called the International Linear Collider.

A competing project, called the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC), has been proposed at CERN, home to the LHC. The IHC plan is thought to be more technologically advanced, but Jean-Pierre Delahaye, CLIC study leader at CERN, told the Associated Press that their machine could be up to 10 times more powerful.

The bigger the atom smasher, the more force the particles can collide with one another and the closer the results will be to simulating the theoretical Big Bang.