Russian Spies Hid Secret Codes in Online Photos

The alleged Russian spies recently arrested by the FBI are accused of encoding messages into otherwise innocuous pictures, marking the first confirmed use of this high-tech form of data concealment in real life, experts say.

The accused spies posted the seemingly mundane photos on publicly accessible websites, but then extracted coded messages from the computer data of the pictures, according to the criminal complaint filed by the FBI. Although computer scientists have theorized about the existence of this communication technique for over a decade, this is the first publicly acknowledged use of the technique.

“There have been occasional claims in the press about al Qaeda using it, but never with any evidence or even attributed to specific government officials,” said Steven Bellovin, a professor in the Columbia University department of computer science. “Here, we have court papers filed by the FBI under penalty of perjury that says these folks were doing it. The threat, in other words, is no longer hypothetical.”

How it works

Although the exact details of what the supposed Russian agents embedded in the pictures, and how they did it, remains classified, the basic technique involves changing the numeric code that computers assign to colors, explained Tal Malkin, an assistant professor in Columbia University’s cryptography laboratory.

To generate the picture on a computer screen, the computer assigns every pixel three numeric values that correspond to the amount of red, green or blue in the color the pixel displays. By changing those values ever so slightly, the spies could hide the 1’s and 0’s of computer language in the picture’s pixel numbers, but without altering the picture’s appearance to the human eye, Bellovin said.

In doing so, the alleged spies were practicing a modern form of "steganography," which refers to the science of concealing messages within images. Early examples include Ancient Greek messages tattooed into the shaved scalps of slaves, and then hidden underneath the re-grown head of hair, according to the classical author Herodotus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The point of standard encryption is to hide the content of the message," Malkin said. "But even if you are detected sending a message no one can read, you will still be suspected by the authorities for sending a coded message.”

“With steganography, you try to hide the fact that communication is going on at all.”

The computerized, picture based, steganography alleged in the FBI criminal complaint dates back to the 1990s, Malkin said. But back then, it was only a theory.

Roots in porn?

After 9/11, rumors began circulating that al Qaeda hid messages inside of pornographic images, Malkin said, although those rumors were never confirmed.

Digital image steganography does have some drawbacks, though. Namely, the spies would need large files to hide even a small amount of information, significantly limiting the size of each message and expanding the time it takes to assemble each one, Malkin said.

But overall, this method provides excellent concealment for hidden messages. First off, the authorities don’t know to analyze a normal looking picture for secret data, said Malkin. And second, with so many pictures on the Internet, the photos containing hidden messages can hide with the safety of numbers.

“The first requirement for a spy's communications is that they not be noticed. In that sense, these methods are excellent,” Bellovin said. “I'm sure there are many billions of pictures on the Internet, and running a steganographic analysis program on all of them is impossible.”

And now, with this first case proving that Internet images with steganographically embedded messages are more than just theory or a rumor, the FBI can only wonder what other messages remain concealed amongst those billions of images.

Lava bursts through Grindavík's defense barriers as new volcanic eruption begins on Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula

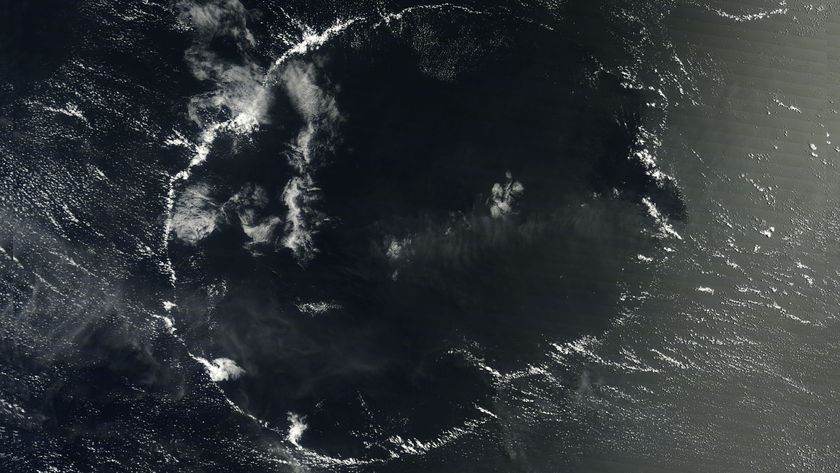

Giant, near-perfect cloud ring appears in the middle of the Pacific Ocean — Earth from space

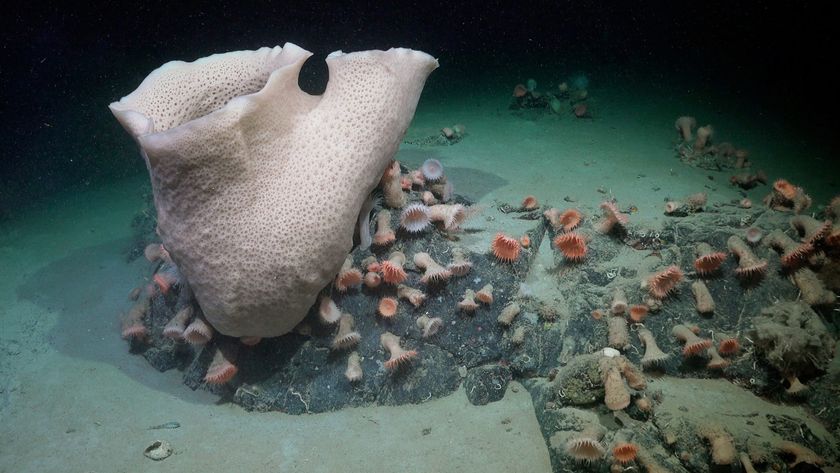

'We didn't expect to find such a beautiful, thriving ecosystem': Hidden world of life discovered beneath Antarctic iceberg