The 10 Strangest Animal Stories of 2019

The animal kingdom is full of cannibals, zombies and party animals.

A wild, wild world

Ants that eat ants, cockatoos that head-bang, and clams that eat their way through stone — one thing's for sure, the animal kingdom can be really wild. This year, scientists stumbled upon all sorts of creatures performing bizarre and mesmerizing behaviors. Here are 10 of the weirdest animal stories we heard this year.

Cannibalistic ants

Ants trapped in an abandoned nuclear bunker in western Poland devoured their dead to survive, according to a study published in November. In 2015, Researchers first stumbled on the cannibalistic ant colony scuttling across the floor of a Soviet military bunker near the German border. Several thousand worker ants had fallen through a pipe in the bunker's ceiling and were unable to clamber back out. On inspection of dead ant carcasses found on the floor, scientists discovered that gnaw marks coated many of the insects' abdomens. But this gruesome tale does have a somewhat happy ending: The researchers installed a ramp for the ants to escape, and when the team returned a year later, most of the ants had left the bunker.

Seagulls don't like being stared at

How can beachgoers keep pesky seagulls from swiping their snacks? Apparently, simply staring at the birds might do the trick, according to a study published in August. Researchers tempted herring gulls in coastal Cornwall with bags of fried potatoes and tested how the birds behaved when they were watched and when they were ignored. Gulls became more cautious about inspecting food when placed under human surveillance, and many of the birds lost interest in the fare altogether. In contrast, when the team ignored the gulls, the birds always pecked at the bag of tasty taters.

Zombie ants

Ants infected by a particular fungus begin to wander around aimlessly, and eventually crawl atop a shrub to die — apparently all under the influence of mind-control, according to a study published in July. The Ophiocordyceps kimflemingiae fungus takes hold of hapless carpenter ants and somehow directs them to bite down hard on a nearby surface, usually the top of a plant. The ant maintains its literal death-grip post mortem, at which point the fungus emerges from the insects' lifeless body and seeks out a new host. Scientists found no evidence that the fungus fiddles with ants' brain cells, but they did identify mysterious particles that may cause the insects' mouth muscles to contract.

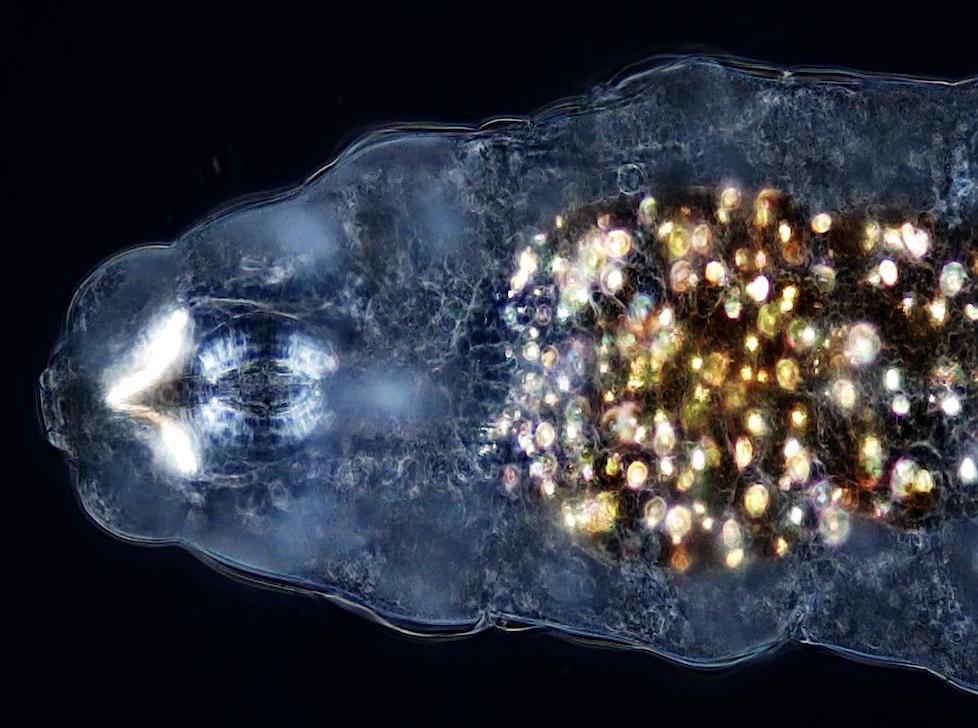

Tardigrades can eat their own mouths

Tardigrades, everyone's favorite near-microscopic invertebrates on six legs, may be able to swallow their own mouths. This year, biologist Rafael Martín-Ledo scooped a tardigrade from the Saja river in northern Spain and discovered strange crystals in the water bear's stomach. Martín-Ledo suspected that the glittering chunks might be bits of aragonite, a mineral made of carbon and calcium that form tardigrades' food-piercing stylets on either side of their mouths. The tiny animals occasionally molt and regrow each stylet, so its conceivable that pieces of their mouth bits sometimes end up in their pudgy bellies.

Head-banging cockatoo

A sulphur-crested cockatoo named Snowball inspired a scientific study of avian dance. Snowball went viral on YouTube when he burst into spontaneous dance to a backtrack of the Backstreet Boys. Intrigued, a team of scientists played other songs for the cockatoo and found that he consistently synchronized his movements to the beat. Snowball even came up with brand new dance moves, improvising different movements to go with specific tunes. The researchers suggested that Snowball's dance moves indicate that humans and birds may share certain musical, social and cognitive abilities.

Cicadas high on fungus

Cicadas infected with a particular fungus develop a drug-like energy rush, engage in a raucous orgy and then literally lose their butts. According to a recent study, the Massopora fungus contains a cocktail of chemicals, including traces of amphetamines and hallucinogens, that send cicadas into a sex-fueled frenzy. Males will even try to copulate with each other and imitate female behavior to attract a mate under the influence of the fungus. The fungus spreads through these sexual exchanges, and also gets released by infected insects in a dramatic spray of disintegrating body parts. "That's why we call them 'flying salt shakers of death," co-author Matt Kasson told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

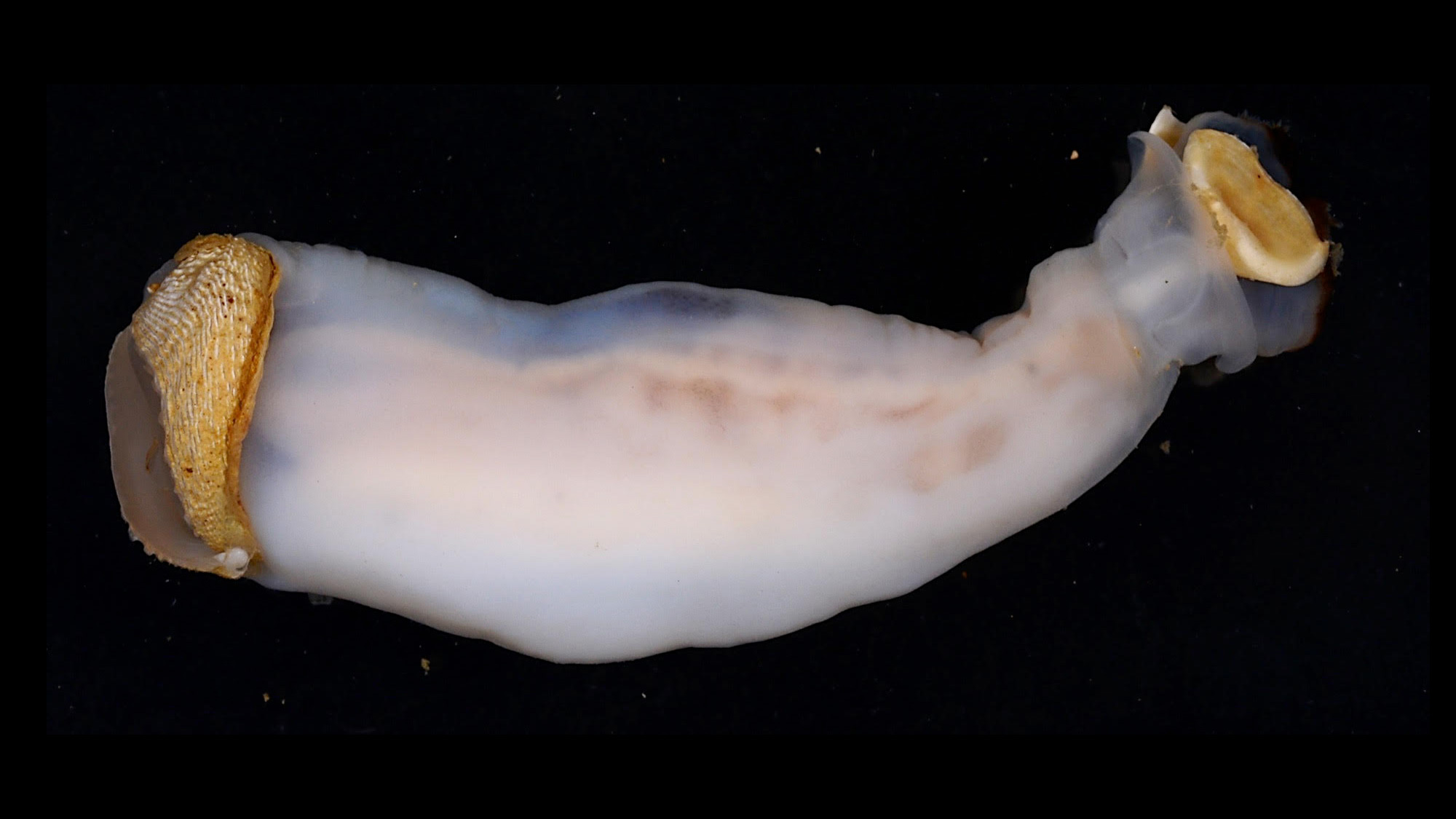

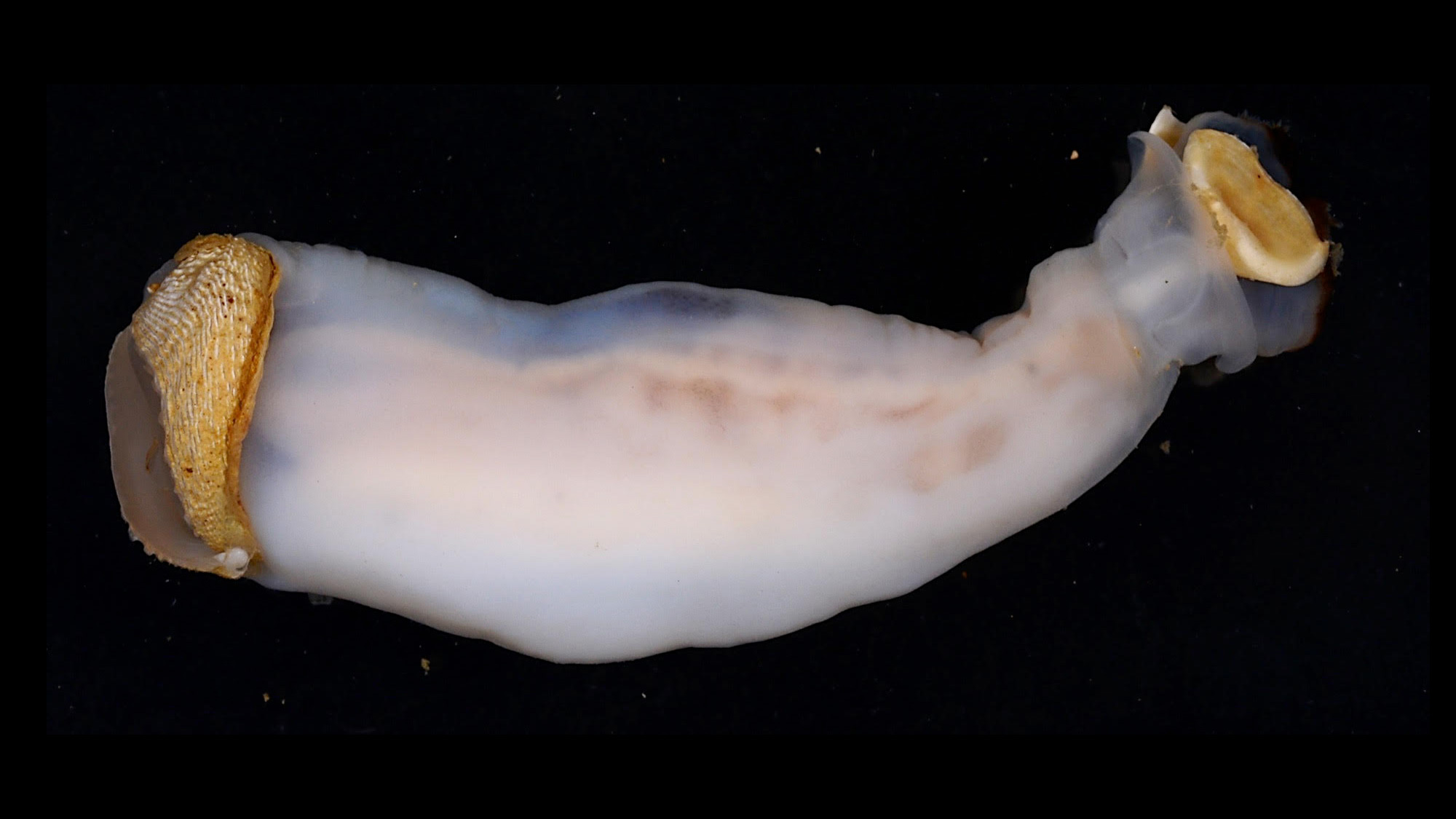

Clam eats rocks for breakfast

This year, scientists discovered an odd-looking clam called a shipworm, whose relatives often nosh on the hulls of wooden vessels. But the team was surprised to find that this particular shipworm has a different favorite snack: rocks. The newfound clam cannot bore into wood like other shipworms do, but instead uses shovel-like projections to dig into rock. The creature crunches up the rock with its shells, gobbles it up and expels the digested minerals as a fine sand. The researchers don't think that the clam gains any nutrients from its gravely diet, but only eats rock to build bigger burrows.

Python vomits up another python

As an Australian man moved a gigantic python away from his house, the animal puked up its last meal — which happened to be another python. The consumed python appeared even fatter than the one that ate it, but measured about the same length, about 11.5- to 13-feet (3.5 to 4 meters) long. One python was able to consume the other by forcing its prey's spinal column into a wave-shape. The "folding" action squashes the animal to fit in the predator snake's stomach, similar to how people squish bulky clothes into small suitcases.

Mice attacked an adult albatross

Invasive house mice took on a full-grown albatross on the World Heritage Site of Gough Island in the South Atlantic. The rodents often kill seabird chicks and eat the birds alive, but no one had never witnessed mice attacking adult albatrosses. Albatrosses lay only one egg every other year, so every loss of an egg, chick or adult matters for population numbers. To protect the species and other birds on the island, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds is working with the government of Tristan da Chunha, a territory of Great Britain, to eradicate the invasive rodents.

Komodo dragons don't need males to reproduce

Female Komodo dragons can produce babies without first receiving sperm from a male, scientists discovered this year. One of the reptiles, named Flora, at London's Chester Zoo, laid eight eggs this year after undergoing parthenogenesis, a "virgin conception." This form of reproduction has been observed in 70 species of vertebrates, including snakes and lizards, but never before in a Komodo dragon. Following parthenogenesis, the unfertilized eggs develop to maturity and produce male offspring, meaning an isolated female Komodo dragon could theoretically start a whole new colony on her own.

- 10 Times Nature Was Totally Metal in 2019

- The 10 Biggest Archaeology Discoveries of 2019

- 9 Epic Space Discoveries You Probably Missed in 2019

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.