Stuxnet Cyberattack on Iran Arms Hackers with New Ideas

Stuxnet, the sophisticated new piece of malware targeting Iranian nuclear facilities, might seem like more of a problem for intelligence services or computer science professors than for the average computer user. But by unleashing the program into the wild, whichever country or organization that created Stuxnet could also be giving criminal hackers a blueprint for producing ever more dangerous computer viruses and worms, experts say.

Security analysts say they have already seen some of Stuxnet’s tricks in malware designed for the more tawdry purpose of personal theft, even though Stuxnet itself is harmless to home computers.

As a result, many experts worry that as nation-states escalate their use of offensive cyberweapons, their advanced technology will leak out of the cloak-and-dagger world and into the criminal underground.

“Stuxnet heralds a new sophistication and a new range of targets that will gradually change the nature of criminal cyber-attacks as much as it will change the nature of national security cyber- attacks,” said Scott Borg, director and chief economist of the U.S. Cyber Consequences Unit, a nonprofit founded by the U.S. government that now independently consults with the government and businesses.

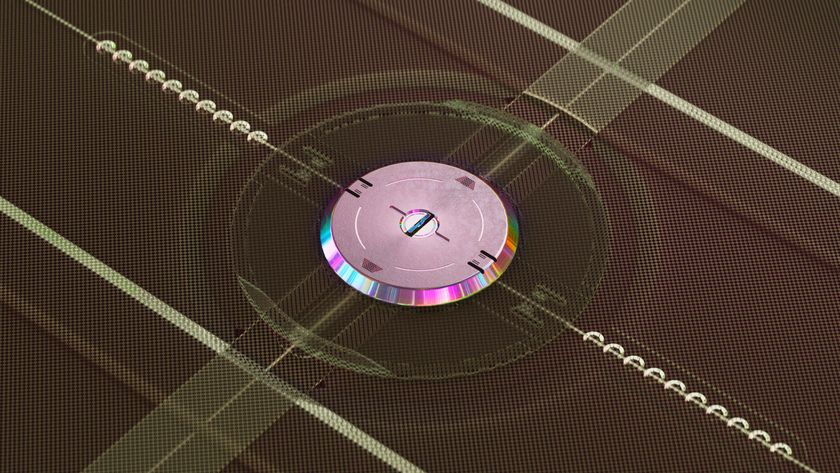

Stuxnet targets a specific piece of industrial equipment made by the German company Seimens, and thus poses no threat to most computers. But it does use previously undiscovered flaws in Windows to access that piece of equipment, and new malware can use those flaws in ways that can affect the common computer user.

As early as March, antivirus companies began detecting criminal malware that exploited some of the same security holes as Stuxnet, said Sean-Paul Correll, a threat researcher at Panda Security, an antivirus software company.

Flaws in Windows that Microsoft engineers have not yet discovered, called zero-day exploits, are much sought after by criminals. According to security experts, cybercriminals pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to the hackers that discover them.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because of the expense of finding and deploying those flaws, most malware uses only one zero- day exploit, if any at all. Stuxnet used four zero-day exploits, all of which are now available to cybercriminals, said Amit Yoran, former director of the National Cyber Security Division in the Department of Homeland Security and current CEO of Netwitness.

Borg, of the U.S. Cyber Consequences Unit, says civilian and nation-state malwares are constantly influencing each other.

“The spyware that intelligence agencies started using aggressively about two and a half years ago was modeled after some civilian spyware," Borg said. "Now the improved versions, developed by the various national intelligence agencies, are being copied by industrial spies-for-hire.”

Of course, considering that cybercrime is already a multimillion-dollar industry, some analysts doubt that hackers need the help. Most cybercriminals are already so advanced that a cyber- arms race prompted by Stuxnet may not provide them with anything they don’t already know, Yoran said.

“I don’t think it really moves the needle a whole lot. They [cybercriminals] are already there,” Yoran told TechNewsDaily. “Maybe the nation-states can do some stuff of a different scale with regards to targeting or coordination, but the professional cybercriminals are already at that level of play.”

Regardless of whether or not criminals benefit from this particular malware, analysts have little doubt that hackers appropriate these kinds of cyberweapons for their own use, even if it’s just in a theoretical or inspirational sense.

“Any cybercriminal can look at the vulnerability and then recreate it for his own cybercrime operation," Correll told TechNewsDaily.