What's Red and Brown and Looks Like a Huge Penguin?

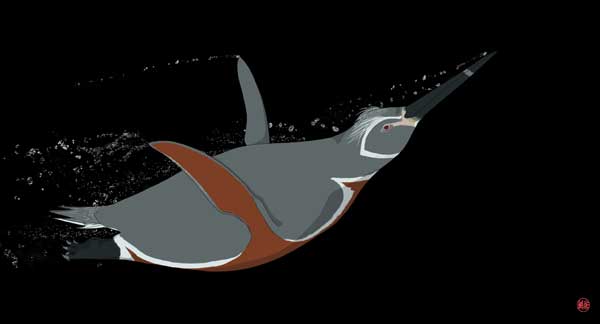

Penguins didn't always boast tuxedo-like black-and-white markings, according to a new study. The discovery of the first ancient penguin fossil with evidence of feathers reveals the aquatic birds were once reddish-brown and gray.

The 36 million-year-old fossil represents one of the largest ancient penguins ever found. The bird would have been 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall, and probably weighed twice as much as modern Emperor penguins, which average about 66 pounds (30 kilograms). Its long, grooved beak suggests that, like modern penguins, it hunted by diving for fish.

Imprints of feathers in the rock around the bones could help researchers understand how modern penguin feathers evolved, said Julia Clarke, a paleontologist at The University of Texas at Austin and a co-author of the paper.

"It's the first evidence of the soft tissues of extinct penguins," Clarke said.

A scaly discovery

The fossil, a new species named Inkayacu paracasensis (or "Water King"), was discovered in the Reserva Nacional de Paracas, a desert preserve on the coast of Peru. Researchers in the field noticed evidence of scaly skin on the fossil foot, prompting suspicion that more evidence of soft tissue might have been preserved. When Clarke examined the specimen in the lab, those suspicions proved true.

"I turned over a flake of rock right near one of the wing elements, and right there was our first evidence of feathering," she told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To find out what color those feathers might have been, the researchers examined the shape of the penguin's melanosomes. These tiny structures resembling pockets contain pigment cells that help give bird feathers their color. The analysis showed that the ancient feathers were likely reddish-brown and gray. [Image of ancient reddish-brown penguin]

"The plumage of these animals was in a very different palette of what we see in living penguins today," Clarke said.

While comparing the ancient penguin's melanosomes to modern birds, the researchers noticed another oddity: Modern penguin melanosomes are different from those of other modern birds. They're broader and clustered in patterns not seen in other species.

Stranger still, the ancient penguin's melanosomes didn't match modern penguins' and instead looked like the melanosomes of other modern birds. The feathers themselves were shaped and stacked like those of modern penguins, suggesting that the ancient penguin had already evolved to swim. The broad melanosomes, however, must have evolved later, perhaps as a way to make feathers more resistant to the wear and tear of swimming underwater, the researchers wrote in the Sept. 20 online edition of the journal Science.

Black-and-white coloring would have evolved later, as camouflage from predators like seals that weren't yet around when the newly discovered penguin species roamed the seas.

From flying to swimming

"It's a quite interesting find, because not only the feather preservation, but also because they found a nearly complete skeleton," said Gerald Mayr, a paleornithologist at the Senckenberg Museum of National History in Germany, who was not involved in the study. However, Mayr said, the theory that physical forces acted on penguin feathers to change the evolution of melanosomes is contradicted by the fact that half of modern penguin feathers are white and contain no melanosomes, despite being subject to the same hydrodynamic forces as melanosome-rich black feathers.

"The main question certainly is, if not due to hydrodynamic forces, why do penguins have such strange melanosomes?" Mayr said.

The new fossil is the first chance researchers have had to ask such questions about how penguin feathers evolved to 'fly' not in the air, but underwater, Clarke said.

"It's a pretty major transition to go from aerial flight to aquatic flight, to flying in a medium that's around 800 times denser than air," Clarke said, adding: "I think there will be more to the story of this penguin's feathering."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.