Dino Demise Led to Evolutionary Explosion of Huge Mammals

Mammals around the world exploded in size after the major extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago, filling environmental niches left vacant by the loss of dinosaurs, according to a new study published today (Nov. 25) in the journal Science.

The maximum size of mammals leveled off about 25 million years later, or 40 million years ago, because of external limits set by temperature and land area, reported an international team led by paleoecologist Felisa Smith of the University of New Mexico.

"For the first 140 million years of their evolutionary history, mammals were basically vermin scuttling around large sauropods and other dinosaurs," Smith said. "They were completely ecologically and competitively inferior to dinosaurs and held in check by these reptiles."

The researchers spent about three years searching the existing literature and an extensive fossil database for information about the evolution of mammal dimensions. They found that many types of mammals living all over the world consistently experienced growth spurts followed by a plateau. By developing a model to explain the growth rate, they discovered that the maximum size leveled off because of ecological constraints, such as the progressive decline in suitable habitats for colossal animals.

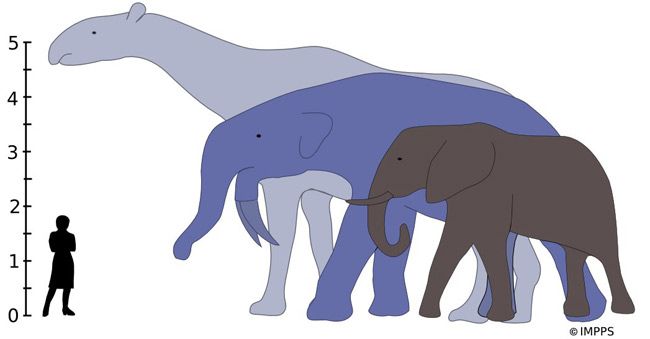

The biggest mammals were plant-eaters that roamed Eurasia and Africa and reached 17 tons — up to five times the mass of an average African elephant, Smith told LiveScience. One of the bulkiest creatures, Indricotherium transouralicum, looked like a cross between a giraffe and a rhino and probably grazed on the tops of trees, while another, Deinotherium, resembled an elephant with a bulbous nose and downward-pointing tusks that curved under the jaw, she said.

Herbivores and carnivores were similar sizes in the period immediately after the mass extinction of dinosaurs, but since about 35 million years ago, the largest meat-eaters have remained about 10 times smaller than the largest herbivores. The reason is that carnivores expend more energy to obtain food, which hampers how large they can grow, said study co-author Jessica Theodor, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary.

The team went on to discover that maximum body size was linked to global temperatures and available land area. Colder temperatures favor the evolution of huge organisms, because they retain heat better than tiny critters as a result of their lower surface-to-volume ratio. Gigantic animals also need greater acreage to find enough food, and the end-Cretaceous extinction provided more open terrain for mammals to thrive and grow.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the size they eventually reached is probably here to stay, Theodor said. "Without a major change in the amount of land available or the amount of plants available, it's unlikely we're going to evolve any larger mammals on land."