Ancient 'Brain Food' Helped Humans Get Smart

Between 1.9 and 2 million years ago, the brain size of our human ancestors increased dramatically. Now a trove of 1.95-million-year-old bone fragments from various animals adds evidence to a theory that these pre-humans owed this brainpower boost to fish.

The fossils, found in northern Kenya, bear cut marks from early stone tools and are the oldest evidence of the consumption of aquatic animals by human ancestors, said study researcher Brian Richmond, an anthropologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. The fatty acids found in the fish could have provided the nutrients the hominins needed to evolve larger brains, he said.

(Hominids include humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and their extinct ancestors, and hominins refer to species after the human lineage split from that of chimpanzees.)

While scientists have proposed a fishy diet as the reason behind the early brain boost, this concrete evidence for our ancestors' diet firms up the speculation.

The study, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also revealed a huge variety in the hominin's diet. The butchered animal bones at the site suggest that antelope, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, catfish and even crocodiles were fair game for late Pliocene diners.

"It's wonderful that you can just come to this one source and see what was being eaten at this site 1.95 million years ago," said Peter Ungar, an anthropologist at the University of Arkansas who was not involved in the study. "They were consuming a much broader range of animals than our nearest living relatives do today."

Butchered bones

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

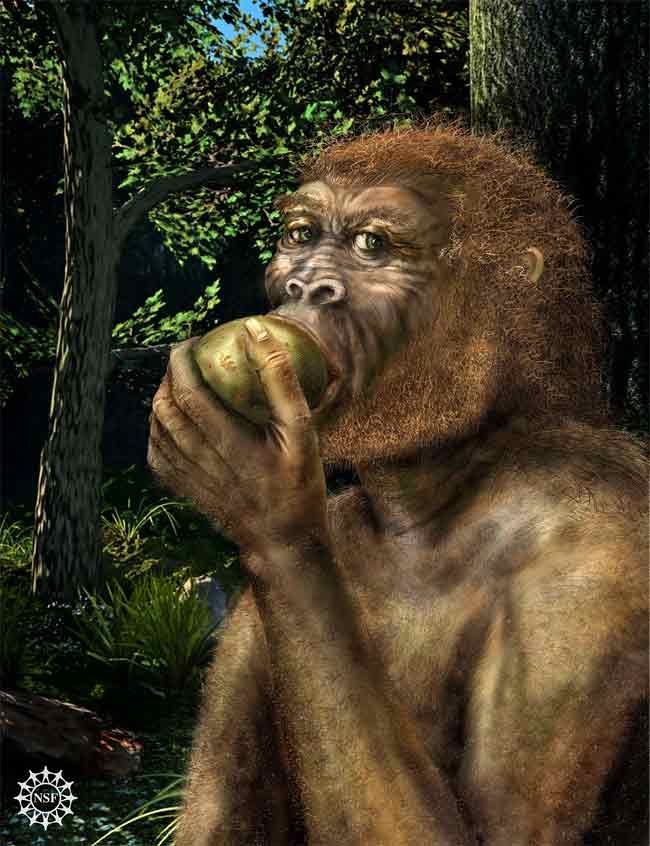

At the time the bones were butchered, the fossil site was wet and forested and was probably near a large river or lake. The research team's excavations revealed 506 fossil bone fragments that could be analyzed for the telltale marks of stone tools.

Six percent of the fragments had cut marks, which is a significant number given that butchering doesn't leave a mark on every bone, Richmond said. Only 1.9 percent of the bones had tooth marks from carnivorous animals, suggesting that the hominins either hunted the meat themselves or scavenged it quickly before other carnivores got to it.

The finding that ancient human ancestors ate fatty-acid rich aquatic animals is exciting, Richmond said, because it could help explain why brain sizes began to increase 2 million years ago.

"A diet that includes animal tissue, especially ones rich in brain-growth nutrients like fish, crocodiles and turtles, lifts the constraints on brain growth," Richmond told LiveScience. "This is the earliest evidence of a substantial contribution of these kinds of foods into the diet of our early human ancestors , and it occurs before we have evidence of a larger brain."

One piece of the puzzle

Still, aquatic animals are just a "piece of the puzzle" of early hominin diet, Ungar said. Eating fish certainly "didn't hurt" in the evolution of large brains, he said, but it may have been the diversity of diet that fueled hominin evolution rather than the individual components.

"It's not necessary to consume those aquatic resources, but it does provide for that dietary breadth," Ungar said.

The researchers can't tell for sure whether early hominins were hunting or scavenging, though the lack of tooth marks from other carnivores does provide for the "uncertain, but very exciting" possibility that our ancestors were hunters, said Osbjorn Pearson, an anthropologist at the University of New Mexico who was not involved in the study.

Either way, Richmond said, our hominin ancestors "were really good at finding meat and acquiring it. They weren't just being the vultures of the Pliocene."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.