Mapping the San Andreas Fault (Underwater and in 3-D)

This past Sunday (Oct. 2) marked the conclusion of a mission that for the first time studied, imaged and mapped the unexplored offshore Northern San Andreas Fault from just north of San Francisco to its end at the junction of three tectonic plates off Mendocino, Calif.

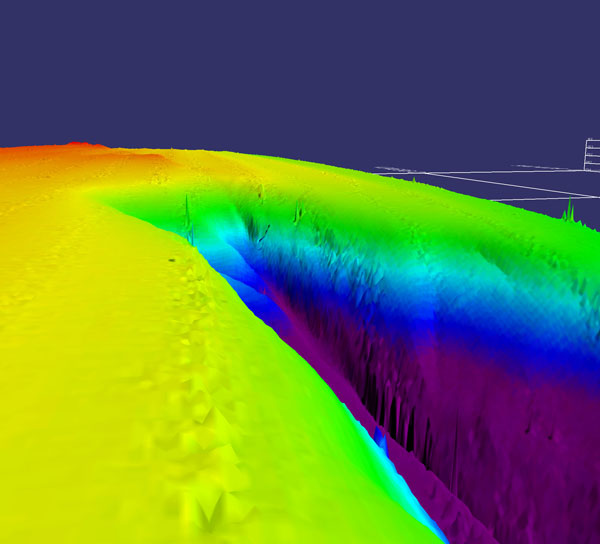

Scientists on the mission, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, have been using various techniques to create the first-ever 3-D structural map that will model the undersea Northern San Andreas Fault and its structure.

By using different types of sonar, they have been able to determine both the depth of the seafloor and obtain information about what type of sediments or hard bottoms are below.

Little is known about the offshore fault due to perennial bad weather that has limited scientific investigations.

Early in the expedition, scientists collected bathymetric (deep underwater) and subsurface data to help them locate specific areas of interest for more detailed operations.

Unlike faults on land, those formed along mid-ocean ridges are very common. While land faults are easily eroded and often cut older faults in complex, hard-to-untangle ways, submarine faults break into newly formed crust without much alteration from erosion.

Scientists expect the subsea portion of the fault to include deep rifts and high walls, along with areas supporting animal life.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"By relating this 3-D model with ongoing studies of the ancient record of seismic activity in this volatile area, scientists may better understand past earthquakes — in part because fault exposure on land is poor, and the sedimentary record of the northern California offshore fault indicates a rich history of past earthquakes," said mission team member Chris Goldfinger, a marine geologist and geophysicist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore.

The researchers explored the fault to determine the relationship between major earthquakes and biological diversity. Evidence shows that active fluid and gas venting along fast-moving tectonic systems, such as the San Andreas Fault, create productive, unique and unexplored ecosystems.

"This is a tectonically and chemically active area," said team member Waldo Wakefield, a research fisheries biologist at NOAA's Northwest Fisheries Science Center. "I am looking for abrupt topographic features as well as vents or seeps that support chemosynthetic life — life that extracts its energy needs from dissolved gasses in the water. I'm also looking at sonar maps of the water column and images of the seafloor for communities of life."

A variety of sensors and systems are being used to help locate marine life, including a NOAA autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) named Lucille. The AUV's high-definition cameras are obtaining multiple images to be stitched into "photo mosaics" showing detailed fault structure and animal life.

The AUV and its sensors can dive to nearly 1 mile (1,500 meters), but depths associated with this expedition ranged between approximately 230 to 1,100 feet (70 to 350 m).

Digital still cameras aboard the AUV used advanced optical cameras to image surface features of the seabed and characterize habitats with their associated life forms. Above the seafloor, a multi-frequency sonar system was used to image animals living in the water column, especially such things as fish schools.

The researchers hope that by mapping the undersea portion of the San Andreas Fault, they will be betterable to predict potential earthquakes and tsunamis because they will have a more complete picture of activity on the fault.

More information about the expedition can be found at NOAA's Ocean Explorer website.