Some Alzheimer's Drugs Very Risky

Widely prescribed anti-psychotic drugs do not help most Alzheimer's patients with delusions and aggression and are not worth the risk of sudden death and other side effects, the first major study on sufferers outside nursing homes concludes.

The finding could increase the burden on families struggling to care for relatives with the mind-robbing disease at home.

"These medications are not the answer,'' said Dr. Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, which paid for the study. He said better medications are at least several years away.

Three-fourths of the 4.5 million Americans with Alzheimer's disease develop aggression, hallucinations or delusions, which can lead them to lash out at caregivers or harm themselves. This behavior is the most common reason families put people with Alzheimer's in a nursing home.

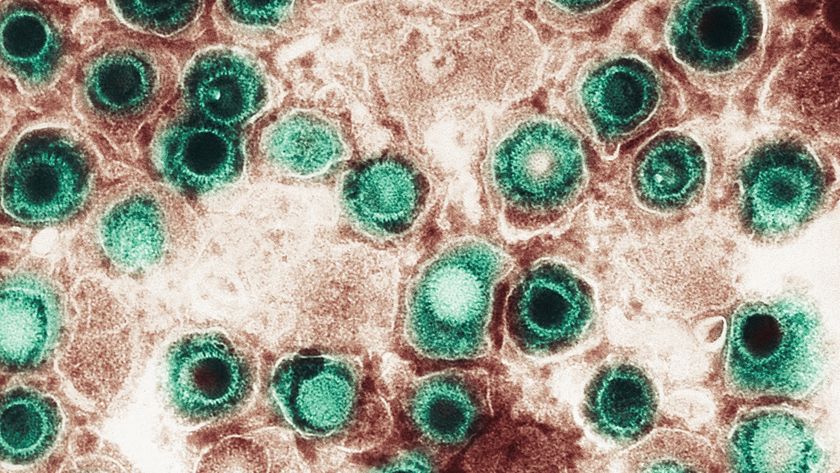

The study tested Zyprexa, Risperdal and Seroquel ─ newer drugs developed for schizophrenia. Doctors are free to prescribe them for any use. However, the drugs carry a strong warning that they increase the risk of death for elderly people with dementia-related psychotic symptoms, mainly because of heart problems and pneumonia, and that they are not approved for such patients.

Yet roughly one-quarter of nursing home patients are on these drugs, and at least that many patients at home have used them, mainly because there are no great alternatives and there was some evidence they might help a little, experts say.

The study tested the drugs on 421 patients at 42 medical centers who needed considerable care but were living in their own home, a relative's or an assisted-living facility. The findings were reported in Thursday's New England Journal of Medicine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each patient got one of the drugs or a dummy pill, without knowing what they received. The doctor could raise the dose if needed. Patients were followed for nine months, longer than in most prior tests.

About four in five patients stopped taking their pills early ─ on average, within five to eight weeks ─ because the medications were ineffective or had side effects that included grogginess, worsening confusion, weight gain, and Parkinson's-like symptoms such as rigidity and trouble walking.

Five deaths were reported among the patients on the medication, versus two among those in the placebo group. But researchers said the difference could be a matter of chance. The causes of death were not disclosed.

Symptoms did improve in about 30 percent of patients taking the drugs, as well as in 21 percent of those getting dummy pills, partly because symptoms can naturally wax and wane.

Some patients who stopped taking one pill were switched to another treatment for the study's second phase, results of which are to be reported next spring.

While the federal government paid for the study, the medications were supplied by the manufacturers: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, maker of Seroquel; Eli Lilly and Co., maker of Zyprexa; and Johnson & Johnson, maker of Risperdal. Most of the researchers have received grants or consulting or lecture fees from the industry.

Dr. Jason Karlawish of the University of Pennsylvania's Alzheimer's Disease Center wrote in an editorial that the drugs did help a small group of patients who had little or no side effects. He said Zyprexa and Risperdal were both better than Seroquel or the placebo in treating the behavioral problems.

Lead researcher Dr. Lon Schneider, director of the Alzheimer's Disease Center of California and a University of Southern California professor, said doctors should try the drugs if necessary, but watch patients closely and switch to something else after a few weeks if there is no improvement or side effects are too severe.

"Patients are put on these kinds of medications and not particularly monitored and treated for indefinite periods of time,'' Schneider said. "That just maximizes risk.''

Schneider said nursing home residents need the drugs more because their behavior problems are generally worse than patients still at home, but their health is more fragile, raising the danger of side effects.

Dr. Claudia Kawas, an adviser to the Alzheimer's Association and a neurology professor at University of California-Irvine, said she sometimes prescribes the drugs. Kawas said that when delusions or aggression develop, it is best to determine if a change in the patient's life triggered the symptoms and whether the behavior can be managed with visits by a health worker.

Also, possible causes such as dehydration, infections and side effects from other medications should be ruled out.

Kawas noted that with the U.S. population aging, the number of Alzheimer's patients is expected to quadruple by mid-century to about 18 million.