Astronomers Find 6-Pack of Planets in Alien Solar System

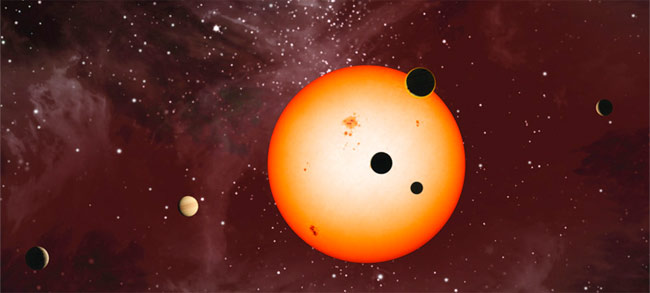

Astronomers have discovered an alien solar system in which six planets are orbiting a sunlike star, with five of the newfound worlds in close-knit configuration.

Few stars have been observed with planetary arrangements like our solar system, making this a compelling find. The newfound exoplanet system was sighted by astronomers using NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space observatory.

The smallest of the new alien planets is about 2.3 times the mass of Earth. None of the extrasolar planets are inside the so-called "habitable zone"—– orbits where liquid water could exist on their surfaces, scientists said.

Astronomers made the serendipitous find after poring over Kepler's observations of the changing brightness of the system's parent star — called Kepler-11 — as the orbiting planets passed in front of the star.

The discovery of five small planets with close orbits around the single star, with another planet farther out with a longer orbit, was unexpected, to say the least, the researchers said. The star Kepler-11 is about 2,000 light-years from Earth.

"We think this is the biggest thing in exoplanets since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b, the first exoplanet, back in 1995," said one of the study's lead authors, Jack Lissauer, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., in a news briefing Monday (Jan. 31).

Lissauer and his colleagues used the Kepler data to analyze the orbital dynamics of the Kepler-11 system and determine the sizes, masses and likely compositions of the planets. The system is compelling because of the number of planets around the host star, their relatively small sizes, and their tightly packed orbits. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Not only is this an amazing planetary system, it also validates a powerful new method to measure the masses of planets," said Daniel Fabrycky, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and one of the co-authors of the new study.

The results of the Kepler-11 study are detailed in the Feb. 3 issue of the journal Nature. They are among the latest discoveries from the Kepler mission, which unveiled a massive amount of data early today that includes hundreds more candidates for potential alien planets. NASA will discuss the latest Kepler discoveries during a 1 p.m. EST (1800 GMT) press conference today.

Meet the Kepler-11 solar system

The five inner planets in the Kepler-11 system range in size from 2.3 to 13.5 times the mass of Earth.

Their orbital periods are all less than 50 days (between 10 and 47 days), which means all five planets and their orbits would fit inside the orbit of Mercury in our solar system.

The sixth planet has an undetermined mass, but it is larger than the other five and follows an orbit that takes it farther from the parent star. It completes one orbit every 118 Earth days.

"Of the six planets, the most massive are potentially like Neptune and Uranus, but the three lowest mass planets are unlike anything we have in our solar system," said Jonathan Fortney, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCSC, who led the work on understanding the structure and composition of the Kepler-11 planets.

More than 100 transiting planets have been observed by Kepler and other telescopes, but the vast majority of them are Jupiter-like gas giants, and almost all of them are single-planet systems. To date, astronomers have confirmed the existence of more than 500 alien planets using ground-based and space-based telescopes.

Before the detection of the Kepler-11 system, astronomers had size and mass calculations for only three exoplanets smaller than Neptune.

Now, measurements from a single planetary system have added five more, and they are among the smallest, Lissauer said.

What are they made of?

Like most of the planets in our solar system, all of the Kepler-11 planets orbit their parent star in roughly the same plane.

These observations reinforce the idea that planets form in flattened disks of gas and dust spinning around a star, and the disk pattern is preserved even after planetary formation, Fabrycky said.

"The coplanar orbits in our solar system inspired this theory in the first place, and now we have another good example," Fabrycky said. "But that and the sunlike star are the only parts of Kepler-11 that are like the solar system."

The densities of the planets, which were calculated from their mass and size, shed some light on their compositions. All six planets were found to have densities lower than Earth's.

"The Kepler-11 system of low mass planets that have low densities implies most of their volumes are made of light elements," Fortney said. "It looks like the inner two could be mostly water, with possibly a thin skin of hydrogen-helium gas on top, like mini-Neptunes. The ones farther out have densities less than water, which seems to indicate significant hydrogen-helium atmospheres."

With scorching hot atmospheres of hydrogen and helium, these planets are not considered habitable, but these results were surprising, since small, hot planets typically have a difficult time holding onto a lightweight atmosphere.

"These planets are pretty hot because of their close orbits, and the hotter it is the more gravity you need to keep the atmosphere," Fortney said. "My students and I are still working on this, but our thoughts are that all these planets probably started with more massive hydrogen-helium atmospheres, and we see the remnants of those atmospheres on the ones farther out. The ones closer in have probably lost most of it."

Part of the equation

The researchers are excited about finding six planets around Kepler-11 because the ability to make valuable comparisons among planets within the same system will help them understand the system's formation and evolution as a whole.

"Kepler-11 is actually telling us a great deal about planets as individual bodies and planetary systems," Fortney said. "Comparative planetary science is how we've come to understand our solar system, so this is much better than just finding more solitary hot Jupiters around other stars."

For instance, the close proximity of the inner planets is an indication that they probably did not form where they are now, Fortney added.

“At least some must have formed farther out and migrated inward. If a planet is embedded in a disk of gas, the drag on it leads to the planet spiraling inward over time," he said. "So formation and migration had to happen early on.”

In search of alien planets

The planet-hunting Kepler space telescope detects planets that transit in front of their host star, causing periodic wobbles in the brightness of the star. The dips in brightness help scientists determine how big a potential planet is in terms of its radius. The time in between transits tells them the orbital period of the planetary candidate.

To determine the mass of the Kepler-11 planets, Fabrycky and his colleagues analyzed slight variations in the orbital periods caused by the gravitational interactions among the planets themselves.

"The timing of the transits is not perfectly periodic, and that is the signature of the planets gravitationally interacting," Fabrycky said. "By developing a model of the orbital dynamics, we worked out the masses of the planets and verified that the system can be stable on longtime scales of millions of years."

The sixth planet in the Kepler-11 system is too far apart from the others that this orbital perturbation method cannot be used to determine its mass, Fabrycky said.

Previously, detections of transiting planets have been corroborated with observations from powerful ground-based telescopes that can confirm the planet and determine its mass using Doppler spectroscopy, which measures the change in the star's motion caused by the gravitational tug of the planet.

In the case of Kepler-11, however, the planets are too small and the star, at 2,000 light-years away, is too faint to use Doppler spectroscopy.

And since the Kepler mission is aimed at finding small, potentially habitable Earth-size planets in our galaxy, the new method of using orbital dynamics could find much broader applications.

"We will need to use orbital dynamics a lot with the Kepler mission to measure the masses of planets; we expect to be doing a lot of these analyses," Fabrycky said.

The spacecraft is scheduled to continue collecting data on the Kepler-11 system for the remainder of its mission, and with the additional data, the researchers hope to make more accurate measurements of the planets and their interactions.

"Not only have we learned a lot to date, but we're going to learn even more as the Kepler spacecraft continues to observe this gem of a system for the remainder of its mission," Lissauer said.

- The Strangest Alien Planets

- Hunting for Earth-like Alien Planets: Q & A with Astronomer Geoff Marcy

- Life's Little Mysteries: A Field Guide to Alien Planets

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com Staff Writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.