In Images: How to Build a Giant Ice Dome

Ice Dome

The team started with a level, sealed working surface where they would construct the ice dome.

Ice Dome

They made the ice by spraying water onto this circular surface and waiting for it to freeze. The team also built a wooden tower in the middle to help support the dome segments during construction. (The steel rods sticking out of the ice were necessary to connect the ice segments to the lifting device later on.)

Ice Dome

Sixteen segments were then cut out of the 8-inch- thick (20 centimeters) plate of ice, each 19 feet (5.8 m) long.

Ice Dome

To sculpt the segments to have a dome-like curve, the researchers relied on ice's creep behavior. If pressure is applied to ice, it slowly changes its shape without breaking. "The segments of ice are placed on stacks of wood. Then, under the load of its own weight, the ice begins to change shape all by itself, resulting in a curved dome segment," said team member Sonja Dallinger, research assistant at the Institute of Structural Engineering and on-site manager of the Obergurgl construction experiment. (The blue steel frame was used to lift the ice segments.)

Ice Dome

Here the creep process is further along, and the ice segments are taking on a more curved shape.

Ice Dome

Each curved segment was fastened with temporary tension chains, which were removed later. Then the pieces were lifted with the help of a crane and fixed to the wooden mounting tower.

Ice Dome

Here, more of the segments have been lifted and fitted to the wooden mounting tower.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ice Dome

Once all the segments had been positioned and the ice dome stood on its own, the team removed the tower.

Ice Dome

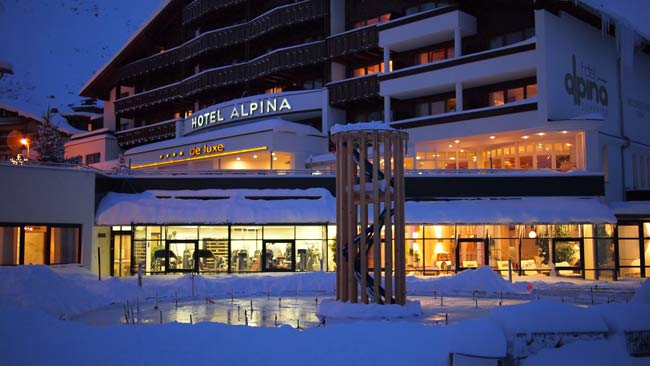

The ice dome, which serves as a bar, at night. The temperatures inside the dome are warmer than one would expect, said the engineers.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.