Foot Bone Puts Prehuman Lucy on a Walking Path

No tip-toeing around it, this foot bone could change the story of human evolution, or at least the story of human foot evolution.

The bone is additional evidence that Australopithecus afarensis, an ancient human ancestor who lived around 3 million years ago, spent most of its time walking, instead of climbing trees like chimps.

"Lucy and her relatives were bipedal, but there had been a debate as to how versatile they were in the trees," said lead researcher Carol Ward, at the University of Missouri in Columbia, referring to the most famous A. afarensis member nicknamed Lucy after a Beatles song. "If they did climb in the trees, they wouldn't have been able to do it any better than you or I would."

One human origins expert doesn't buy the conclusions, however, saying other Lucy-aged bones point to a combination of tree climbing and ground walking.

Foot bone

The bone in question belonged to one of Lucy's A. afarensis kin who died about 3.2 million years ago. It was discovered in Hadar, Ethiopia, on a plateau so rich with fossils from this era that it's called the "first family site."

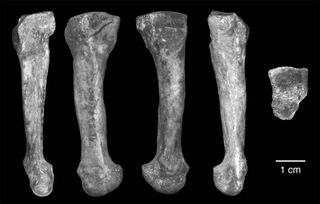

The bone comes from the outside of the foot, near the pinky toe, and is a stiff part of the arch bone that acts like a lever when walking on two feet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Arches were an important part of our evolution into humans, because they make climbing trees much harder. The arches on the inside of the foot, nearer to the big toe, serve as a shock absorber when we plant our feet back on the ground. All other living primates have feet made for grasping and bending to hang onto tree branches and their young, more like our hands than our feet.

Their analyses revealed the bone matched up best with human foot bones, suggesting, Ward said, that Lucy and her Australopithecus kin would have spent time in the trees only when chased there by predators or to harvest food from its branches. "Selection wasn't favoring the ability to be effective in the trees, it was favoring being effective on the ground," Ward said.

"That's a big deal because that means arches, and not just precursors, real full-grown arches, go back three, three and a half million years," said Jeremy DeSilva, from Boston University, who was not involved in the study. "It really helps us understand this uniquely human feature, this arch."

Down from the trees

An inkling of Lucy's saunter came in 1976, when scientists discovered footprints in volcanic ash left behind 3.5 million years ago by three creatures in Laetoli, Tanzania. Though the footprints had distinct arches, figuring out who made them was tricky and has been long debated in the archeological world.

And only a few arch bones from early humans have been found, making it difficult to determine if Australopithecus had arches.

"Those of us who work on feet and early human foot morphology, arches have been tough because they are soft tissue, and they don't really fossilize," DeSilva, who studies locomotion in the earliest apes and early human ancestors, told LiveScience. "What you look for are skeletal hints, or correlates of the presence of an arch, and as a field we haven't really been able to agree on what those are."

Scientists don't have a very clear grasp on how bones evolve, either, DeSilva said. Use of bones during movement can shape the bone scaffolding laid down by genes during development. And so it's hard to isolate features of these fossilized bones that would've been the result of the walking styles of a few individuals versus an adaptation that evolved in a group of organisms.

But previous studies of ankle, toe and heel bones convinced DeSilva. "I wouldn’t say that from a single metatarsal [foot bone] you can reconstruct the entire locomotion of an animal, but from all of the other evidence that's been presented from the waist down, they were obligate walkers," DeSilva said.

"These things are moving very similar to the way we are, the way we do today and they were not spending much time up in the trees," DeSilva said, though he noted that there are differences in the pelvic region that suggest Lucy and her kin might have walked with a slightly different gait.

Or still hanging around?

But this new evidence hasn't swayed everyone.

William Harcourt-Smith, from the City University of New York and the American Museum of Natural History, disagrees with Ward and DeSilva. Though he said the analysis of the bone is well-done, he still believes that Lucy could have spent as much as 50 percent of her time climbing, and would have been comfortable in the trees.

"You look at this one bone, it looks very humanlike, and you can't disagree with the analysis, but it only tells part of the story," Harcourt-Smith told LiveScience. "If you want to know how it [Australopithecus] walked around you have to look at all of the evidence available."

Harcourt-Smith also notes that a bone from the inside of the foot, where the arch is the strongest, would be more convincing. When Harcourt-Smith looks at other parts of Australopithecan anatomy, including its curved toe bones and another foot bone called the navicular bone, he comes to different conclusions.

"It [Ward's bone] is obviously quite humanlike," Harcourt-Smith said. "But you look at the other bones and you have a mosaic of adaptive features," meaning features for tree climbing as well as walking on the ground.

DeSilva notes that Australopithecus does have climbing adaptations, including indications of a strong upper body, which would have encouraged climbing, but which he said could also be used as adaptations to carry food or babies when walking on two feet.

"They have their own interesting adaptations and anatomies and peculiar ones which have been difficult to figure out if they are evolutionary carryovers or if they are adaptations," DeSilva said. "These are not scaled-down humans."

An analysis of the bone will be published in the Feb. 11 issue of the journal Science.

You can follow LiveScience Staff Writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.