11 Facts Every Parent Should Know About Their Baby's Brain

Fascinating Baby Brains

Most of them are bald, fat and speak only nonsense. And we couldn't be more fascinated. What is going on inside the infant noggin? Here are 11 facts about the baby's brain every parent should know.

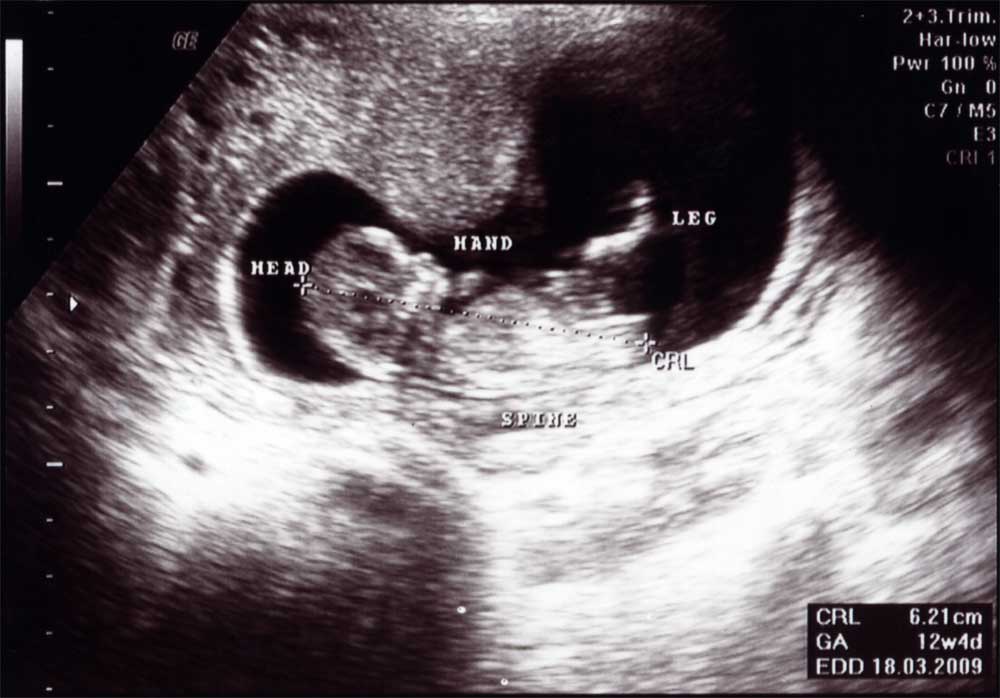

All babies are born too early

If it weren't for the size limitations of a woman's pelvis, babies would stay developing in the womb for considerably longer, comparative biologists have suggested.

"We have to keep our pelvises relatively narrow to keep upright," said Lise Eliot, neuroscientist and author of What's Going on in There? How the Brain and Mind Develop in the First Five Years of Life (Bantam, 2000). To fit through mom's, er, escape hatch, the newborn brain is one-quarter the size of an adult's.

Accordingly, some pediatricians label a baby's first three months of life as the "fourth trimester" of pregnancy to emphasize how needy, and yet devoid of social skills, babies are at this stage. The first social smile, for example, doesn't usually appear until the infant is 10-14 weeks old and the first phase of attachment, scientists suggest, begins around five months old.

Some evolutionary biologists theorize that newborns are socially inept – and have an annoying cry – so that parents won't get too emotionally attached while the baby has an increased likelihood of dying. Of course, crying also gets a baby the attention he needs to survive.

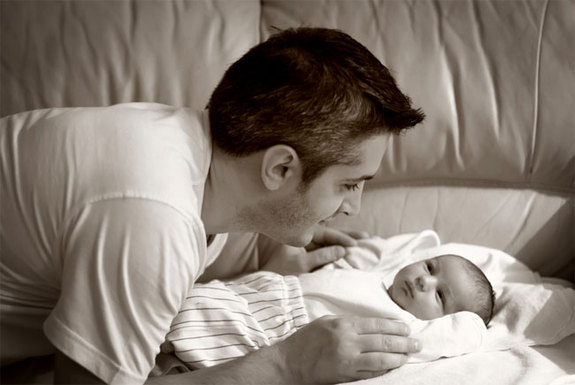

Parental responses wire baby's brain

"As long as there have been babies, there have been parents," said Michael Goldstein, a language development researcher at Cornell University. The baby's brain has evolved to use the responses of caregivers to help it develop, Goldstein told LiveScience. The newborn prefrontal cortex – the brain's so-called "executive" area – doesn't have much control, so efforts to discipline or worries about spoiling are pointless at this stage. Instead, newborns are learning about hunger, loneliness, discomfort and fatigue – and what it feels like to have these pains relieved. Caregivers can help this process along by promptly responding to baby's needs, experts suggest.

Not that a baby can be kept from crying. In fact, all babies, no matter how responsive their parents are, have a period of peak crying around the gestational age of 46 weeks. (Most babies are born between 38 and 42 weeks.)

Experts, such as neuro-anthropologist and author of "The Evolution of Childhood" (Belknap, 2010) Melvin Konner, think some early wails are tied to physical development, noting that across cultures crying peaks at the same point after conception, independent of when the baby makes its entrance into the world. That is, a premature baby, born at 34 weeks, will reach her peak crying point at around 12 weeks old, while a full-term baby, born at 40 weeks, will cry the most at around 6 weeks old.

Silly faces and sounds are important

When babies imitate the facial expressions of their caregivers, it triggers the emotion in them as well, explains Alison Gopnik in her book "The Philosophical Baby" (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009). This helps infants build on their basic innate understanding of emotional communication and may explain why parents tend to make exaggerated happy and sad faces at their little ones, making them easier to imitate. Parentese, or baby talk, is another seemingly instinctual response that researchers have found is critical to infant development. Its musicality and exaggerated, slow structure emphasizes critical components of a language, helping a baby grasp words, Eliot told LiveScience.

Baby's brain grows like evolution on steroids

When first born, the brains of humans, apes and Neanderthals are much more similar than they will be by adulthood.

After birth, the human brain grows rapidly, more than doubling to reach 60 percent of its adult size by the time the tot is sampling his first birthday cake. By kindergarten, the brain has reached its full size but it may not finish developing until the kid is in his mid-20s, Eliot told LiveScience. Even then, Eliot qualified, "the brain never stops changing, for better or worse."

Some scientists speculate that the changes in the developing infant brain mirror, on a rapid scale, the changes that have been shaped over eons of evolution.

Lantern (vs. flashlight) awareness

Baby brains have many, many more neuronal connections than the brains of adults. They also have less inhibitory neurotransmitters. As a result, researchers such as Gopnik have suggested, the baby's perception of reality is more diffuse (read: less focused) than adults. They are vaguely aware of pretty much everything – a sensible strategy considering they don't yet know what's important. Gopnik likens baby perception to a lantern, scattering light across the room, where adult perception is more like a flashlight, consciously focused on specific things but ignoring background details.

As babies mature, their brains go through a "pruning" process, where their neuronal networks are strategically shaped and fine-tuned by their experience. This helps them make order out of their worlds, but also makes it harder to innovate and come up with such breakthroughs as spinach puree face paint.

Creative people, Gopnik and others have argued, have retained some ability to think like an infant.

Babbling signals learning

Within their lantern's light, babies do focus however momentarily. And when they do, Goldstein told LiveScience, they usually make a sound to convey interest. In particular, babbling – the nonsense syllables babies spout – is "the acoustic version of a furrowed brow," Goldstein said, signaling to adults that they are ready to learn. Ambitious parents may want to keep an ear out for this signal, Eliot said. "The only thing we know of, that makes babies smarter, is talking to them," she told LiveScience, emphasizing that dialogue is best, where a parent responds within the pauses of an infants' vocalizations.

Incidentally, the word "baby" may come from this babbling, as in "the one that says ba-ba-ba."

There is such thing as being too responsive

Some parents take Eliot's advice too far and strive to meet Junior's every yip with a yap. But when babies get a reaction 100 percent of the time, they get bored and look away. Worse, "their learning is very delicate," Goldstein said: It won't last the first inevitable time they don't get the reaction they expect.

When acting instinctually, parents respond to 50 to 60 percent of a baby's vocalizations. In the lab, Goldstein has found that language development can be sped up when babies are responded to 80 percent of the time. Beyond that, however, learning declines.

Parents also naturally "raise the babble bar," Goldstein told LiveScience, by slowly responding less to sounds they have heard a baby make many times (like "eh"), but excitedly repeating a new sound that comes closer to a word (such as "da".) In this way, the baby starts to piece to together the sound statistics of his language.

Educational DVDs, tapes, etc. are worthless

While from birth babies may cry with the intonations of their mother tongue, recent research emphasizes that social responses are fundamental to a child's ability to fully learn language.

"Babies divide up the world between things that respond to them and things that don't," Goldstein said. And things that don't, don't teach. A recording does not follow a baby's cues, which is why infant DVDs, such as Baby Einstein and Brainy Baby, have been found to be ineffective, he explained.

If you want to help your baby to be smart, throw out the flashcards and videos, Eliot said, and play with your baby.

Their brains can become overwhelmed.

But their need for human interaction doesn't mean they should be tickled senseless day and night.

Babies have short attention spans and can easily be over-stimulated, Eliot said. So sometimes, the interaction they need is simply help calming down. This can be provided by rocking, dimming lights or swaddling flailing limbs that babies have yet to figure out how to control, Eliot said. Being able to not only calm down but also sleep, especially during the night, may enhance skill development, at least for babies 12 months and older, suggests a 2010 study in the journal Child Development.

Darling but deaf?

Babies are rather hard of hearing, Eliot said, "which may be why their crying doesn't seem to bother them as much as it bothers us."

And in general, children can't distinguish voices from background noise as well as adults can, she continued. So underdeveloped auditory pathways may explain why infants sleep peacefully in crowded areas or next to a roaring vacuum – and why Izzy doesn't respond to shouts to come off the playground.

For the same reason, constantly having music or the television on in the background can make it harder for babies to distinguish the voices around them and pick up language, Eliot said. (Babies can't learn to talk from the TV or radio; see #7.)

Although babies often love music, Eliot suggests, "music should be a focused activity, not background noise."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Robin Nixon is a former staff writer for Live Science. Robin graduated from Columbia University with a BA in Neuroscience and Behavior and pursued a PhD in Neural Science from New York University before shifting gears to travel and write. She worked in Indonesia, Cambodia, Jordan, Iraq and Sudan, for companies doing development work before returning to the U.S. and taking journalism classes at Harvard. She worked as a health and science journalist covering breakthroughs in neuroscience, medicine, and psychology for the lay public, and is the author of "Allergy-Free Kids; The Science-based Approach To Preventing Food Allergies," (Harper Collins, 2017). She will attend the Yale Writer’s Workshop in summer 2023.