Thunder Thighs: New Dinosaur Had a Colossal Kick

Anyone who's ever thought they had a big butt had nothing on a dinosaur literally named "thunder thighs."

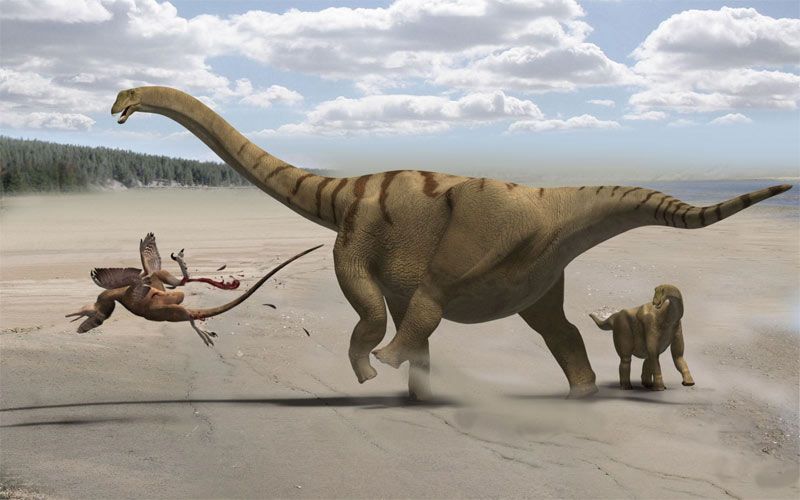

Among the sauropods, the largest creatures to have ever walked the Earth, Brontomerus — "thunder thighs" in Greek — probably had the biggest thighs of them all, scientists revealed. Its unusually powerful back legs might have been used for super-kicks against rivals or would-be predators, they added. [Illustration of Brontomerus]

Partial skeletons of Brontomerus mcintoshi were recovered in 1994 in a quarry in eastern Utah. (The dinosaur's species name, mcintoshi, is meant to honor of John "Jack" McIntosh, a retired physicist and sauropod expert.)

The fossils remained in a museum until scientists recently noticed their unusual structures.

"This specimen just leaps out at you and looks weird," researcher Mike Taylor, a paleontologist at University College London, told LiveScience.

Two specimens were discovered, an adult and a juvenile, and paleontologists conjecture that the larger specimen was the mother of the younger — sauropods are often found in what seem to have been family groups. The larger specimen would have measured 42 feet (14 meters) long and weighed about 13,200 pounds (6,000 kilograms), roughly the size of a large elephant. The smaller dinosaur was about a third as long at about 14 feet (4.5 m) and weighed about 440 pounds (200 kg), the size of a pony.

Among the skeletons was a hip bone that had an unusually wide surface projecting forward from the hip socket, providing a relatively large area for muscles running down the front of the leg to attach to. This structure indicates that Brontomerus likely had the largest leg muscles of any dinosaur in the sauropod family.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The best we can work out, it could project its leg forward very powerfully — in short, for kicking," Taylor said. "We think the most likely reason this evolved was over competition for mates, with males fighting each other or just showing off to win affection of females."

However, once such powerful kicking muscles evolved, "it would be bizarre if it wasn't also used in predator defense," Taylor added. Brontomerus lived about 110 million years ago, and probably had to deal with fierce "raptors," such as Deinonychus and Utahraptor, as well as Acrocanthosaurus, a giant predator similar in size to T. rex.

At the same time, the shoulder blade of the dinosaur had "unusual bumps that probably mark the boundaries of muscle attachments, suggesting that Brontomerus had powerful forelimb muscles as well," said researcher Matt Wedel, a paleontologist at the Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, Calif. "It's possible that Brontomerus mcintoshi was more athletic than most other sauropods."

Such powerful legs could have enabled this giant to go far.

"It is well established that far from being swamp-bound hippo-like animals, sauropods preferred drier, upland areas, so perhaps Brontomerus lived in rough, hilly terrain and the powerful leg muscles were a sort of dinosaur four-wheel drive," Wedel said.

Unfortunately, when the researchers discovered the quarry where these bones were found, it had already been looted. "Part of the frustration is that we may never know how much of a problem this looting caused," Taylor said. "It may have been there was a whole animal in the ground there, with just bits pulled up piecemeal and shoved on someone's mantelpiece. It's possible we lost a really beautiful specimen there, or more than one."

Future research can aim at further digging in the quarry to find more Brontomerus fossils. Those of the thigh and base of its tail would reveal a lot more about its kicking power.

"This is all part of a trend of scientists discovering more and more new dinosaurs — it's almost a frightening rate, something like two a week, so our understanding of dinosaur diversity is going through the roof," Taylor said. "And it's extraordinary how much dinosaur material is just in museums having never been studied. It's a great privilege to work on without having to get my hands dirty in the field."

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 23 in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.