Voyage's Close Calls Produce Better Maps of Undersea Mountains

Our knowledge of the ocean floor has many gaps; maps based on satellite data contain only the roughest of details. A scientific cruise is using sonar to fill in the picture along its path from South Africa to Chile.

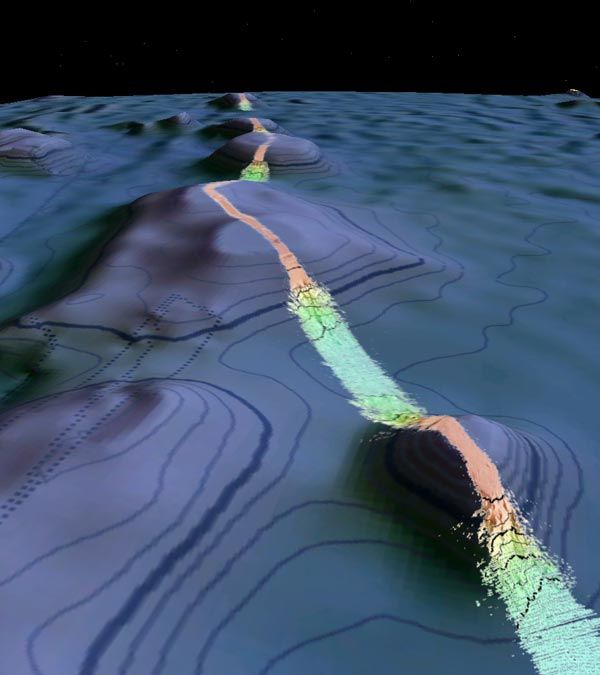

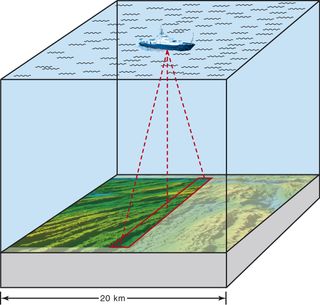

Since a U.S. Navy research vessel, the Melville, departed from Cape Town Feb. 20, geophysicist Joseph "JJ" Becker has been mapping underwater mounts as tall as 14,800 feet (4,500 meters), using a sonar system that bounces sound off the seafloor and analyzes the signal that returns. [Image of undersea mountains]

The satellite data don't offer precise information about the height of seafloor mountains, so for the crew of the Melville, passing over them can be tense. In one case, the satellite data predicted the peak of a mountain would be 19.7 feet (6 m) below the surface. The ship draws almost the same depth. During the approach, Becker and the ship's captain carefully monitored the mountain below them on the sonar to make sure they weren't going to run aground. Meanwhile, someone else kept an eye out for rocks or shoals.

Even a sonar-detected depth of 984 feet (300 m) was cause for concern in the open ocean, where some spire could have gone uncharted. "In real life, this is a bit like driving your car toward a brick wall, calculating how many seconds it will take to hit the wall and being ready to slam on the brakes at the last minute," Becker told OurAmazingPlanet.

Rough ride

As of Monday (March 7), the Melville had crossed the South Atlantic and was heading past the Falkland Islands. Unreachable by phone, Becker answered questions by e-mail, although at one point on Friday (March 4), a rough sea forced him to cut short a reply.

"The boat was rocking about 20 degrees to each direction, 40 total. That's enough that even if you are sitting in a chair, the chair can fall over, so I had to give it a rest," Becker wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Only about 7 percent of the deep ocean has been mapped using ship data, according to David Sandwell, a professor of geophysics at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California. Sandwell tweaked the Melville's route to take it above an interesting-looking area en route to Valparaiso in central Chile.

"Take one of our ships with a multibeam echo sounder" – the sonar system. "It would take 125 years to map the deep ocean basin completely," Sandwell said. "So you can see the problem here, it’s just a huge area and ships go slowly."

Oceanographers use satellite measurements of the shape of the ocean's surface to create a rough picture of the ocean floor. Large features under the sea are massive enough to change the gravity field at the surface, attracting water and causing bumps in the ocean surface. Satellite radar can detect these bumps and dips, Sandwell explained.

Taking the long way

The main point of this voyage is to get the Melville, which is operated by Scripps, from Cape Town to Valparaiso, where it will pick up other researchers intent on studying the effects of last year's Chilean earthquake on the seafloor. In order to make the best of the transit trip, Scripps populated the ship with scientists, including Becker.

About six months ago, Sandwell began planning the ship's route, devising a track that deviated slightly, by 3 percent, from the most direct route. Bad weather as they left Cape Town forced Scripps to revise the track line, but it is equally interesting to the first, Sandwell said.

Becker compared it to leaving Interstate 80 during your drive from San Francisco to New York to see sites like Yellowstone.

"I think the important message is that if we can get the research ships to take even a 20-mile detour on a 5,000-mile voyage [32 km on top of 8,050 km], we will discover endless new features; seamounts, valleys and things we can’t imagine," Becker wrote.

You can follow LiveSciencesenior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry.