Alzheimer's Disease May Start in the Liver, Study Suggests

The protein that forms plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease may have its origins in the liver, a new study in mice suggests.

The researchers said that targeting the liver's production of this protein, called beta amyloid, may be a new way to treat Alzheimer's.

In fact, the researchers tested their theory by treating mice with a drug that could not cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain. They found the drug significantly reduced levels of beta amyloid in both the blood and the brain. This suggests a considerable amount of beta amyloid found in the brain is produced elsewhere, they said.

The researchers were surprised by their findings.

"Everybody has assumed that it’s the amyloid that originates in the brain that causes the brain disorder," said study researcher Greg Sutcliffe, of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif. "Had I not seen the data, I would have scoffed at the idea that it might come from someplace else," he said.

"I think it's possible to foresee a day not too far away when Alzheimer's becomes completely preventable," Sutcliffe said.

However, other researchers said that there is evidence suggesting beta amyloid production in the brain is important in Alzheimer's disease. For example, studies have shown that genes that contribute to Alzheimer's increase beta amyloid production in the brain, said William Thies, chief medical and scientific officer at the Alzheimer's Association.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And there is not yet enough data to know whether beta amyloid produced outside of the brain is enough to cause Alzheimer's, or whether blocking its production could treat the disease, Thies said.

"It may or may not be sufficient to contribute to or allow us a therapeutic pathway for Alzheimer's disease," Thies said.

And while Thies agreed the disease will one day be preventable, it may not be so soon, or may not occur as a result of this finding. "You could have any number of reason [a treatment that targets the liver] might fail," he said.

Studying genes

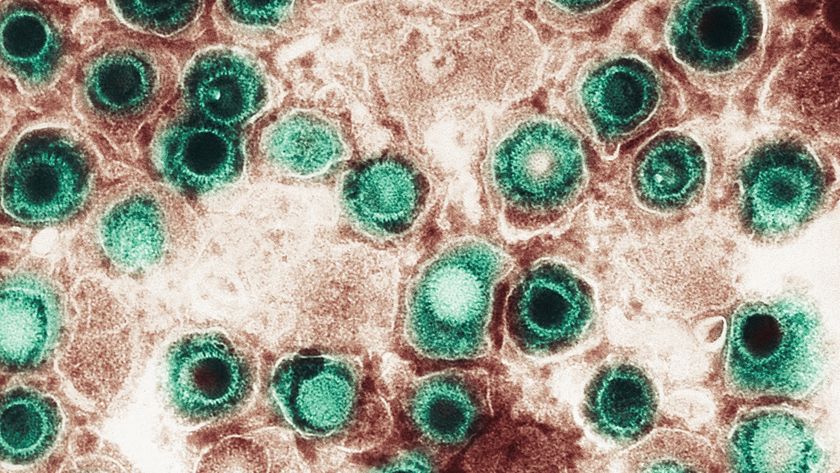

The researchers compared two strains of mice that were genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer's disease. Earlier work had found that one strain was protected against the buildup of beta amyloid in the brain, compared with the other.

Sutcliffe and his colleagues identified three genes that could confer such protection. They showed that cells in the liver of the protected mice did not express, or turn on, these genes, as much as liver cells of the other mice. Further, they found this lower level of expression protected against accumulation of beta amyloid in the brain.

One of these genes, called Presenilin 2, is involved in the production of beta amyloid, and has been linked to early onset Alzheimer's disease in humans. But previous work had focused on expression of this gene in the brain, not other tissues that produce beta amyloid, Sutcliffe said.

"The genetics say that it’s the amyloid that’s produced outside of the brain that's causing the accumulation," Sutcliffe said.

A new drug for Alzheimer's

The researchers wanted to give the mice a drug that would reduce levels of beta amyloid in only the blood. They chose the drug Gleevec (which is used to treat leukemia) because it cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. Gleevec had previously been shown to reduce the amount of beta amyloid in the brain when pumped into the brain, but researchers had not yet looked for this effect after injecting it into the bloodstream.

They saw that administering Gleevec for a week reduced the amount of beta amyloid in the brain by 50 percent, even though the drug cannot get into the brain.

The next step would be to conduct a clinical trial to see if the same holds true in humans, Sutcliffe said. A trial could examine whether Gleevec reduces beta amyloid in the spinal fluid of Alzheimer's patients, or individuals prone to developing Alzheimer's, such as those with Down syndrome, Sutcliffe said.

Because Gleevec is already approved by the FDA, clinical trials testing the drug as a treatment for Alzheimer's might be expedited, Thies said.

Sutcliffe and other researchers involved with the study are members of ModGene, LLC, a preclinical research company.

Pass it on: The plaques that cause Alzheimer's disease may have their origins in the liver, not the brain. However, this needs to be confirmed in people.

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.