At Solar System's Edge, Old Voyager 1 Probe Performs New 'Acrobatics'

A venerable NASA spacecraft cruising toward the edge of the solar system has proved that it's not ready to retire just yet by performing a precision maneuver to gear up for new studies of the solar wind.

NASA's Voyager 1 probe, which launched in 1977, rolled itself 70 degrees counterclockwise on Monday (March 7), and then held the position for more than two hours. The goal was to start positioning the probe — humanity's most distant spacecraft — to study how the charged particles streaming from the sun behave deep in space.

It was the first such roll-and-stop move for Voyager 1, or its sibling Voyager 2, since 1990, NASA researchers said. However, the spacecraft have performed rolls — without any stops — regularly in the intervening decades, to help calibrate their instruments and take data on the sun's magnetic field, the scientists added.

"Even though Voyager 1 has been traveling through the solar system for 33 years, it is still a limber enough gymnast to do acrobatics we haven't asked it to do in 21 years," Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "It executed the maneuver without a hitch, and we look forward to doing it a few more times to allow the scientists to gather the data they need." [The Solar System Explained: From the Inside Out]

A solar wind mystery

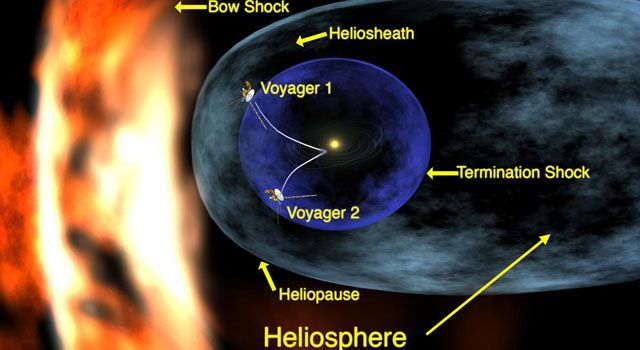

The two Voyager spacecraft are traveling through a turbulent region of the solar system known as the heliosheath. The heliosheath is the outer shell of a bubble around our solar system created by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles blowing outward from the sun at a million miles per hour.

Astronomers believe that the solar wind banks as it approaches the outer edge of this bubble, where it runs up against the interstellar wind. The interstellar wind originates in the region between stars, and it blows by our solar bubble, researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In June 2010, when Voyager 1 was about 10.6 billion miles (17 billion kilometers) away from the sun, data from its Low Energy Charged Particle instrument showed that the net outward flow of the solar wind was zero. That zero reading has continued since.

The Voyager science team doesn't think the wind has disappeared in that area — it has likely just turned a corner, in line with predictions. But they're not sure about the details of that turn — whether the solar wind goes up, down or to the side, researchers said.

Voyager 1 could help them get to the bottom of this mystery.

"Because the direction of the solar wind has changed and its radial speed has dropped to zero, we have to change the orientation of Voyager 1 so the Low Energy Charged Particle instrument can act like a kind of weather vane to see which way the wind is now blowing," said Edward Stone, Voyager project manager, based at Caltech in Pasadena. "Knowing the strength and direction of the wind is critical to understanding the shape of our solar bubble and estimating how much farther it is to the edge of interstellar space."

Rolling at solar system's edge

Researchers performed a test roll-and-hold maneuver with Voyager 1 on Feb. 2 for two hours, 15 minutes. When data came down to Earth 16 hours later, the mission team verified the test was successful: The spacecraft had no problem reorienting itself and locking back onto its guide star Alpha Centauri, researchers said.

The spacecraft's Low Energy Charged Particle instrument science team confirmed that Voyager 1 had acquired the kind of information required, and mission planners gave the probe the green light to do more rolls and longer holds.

There will be several more of these maneuvers over the next week or so, with the longest hold lasting nearly four hours, researchers said. The Voyager team plans to execute a series of weekly roll-and-stops for this purpose every three months for the foreseeable future.

The maneuvers will have little impact on the long-lived spacecraft's fuel supply. Voyager 1 still has about 57 pounds (25.9 kilograms) of hydrazine propellant left, and each roll-and-stop uses just 3.5 ounces (100 grams) of the stuff, Dodd told SPACE.com.

"We do whatever we can to make sure the scientists get exactly the kinds of data they need, because only the Voyager spacecraft are still active in this exotic region of space," said Jefferson Hall, Voyager mission operations manager at JPL. "We were delighted to see Voyager still has the capability to acquire unique science data in an area that won't likely be traveled by other spacecraft for decades to come."

Long-lived space voyagers

Voyager 2 was launched on Aug. 20, 1977. Voyager 1 was launched on Sept. 5, 1977. Both spacecraft were originally tasked primarily with studying Jupiter, Saturn and their moons.

On March 7, Voyager 1 was 10.8 billion miles (17.4 billion km) away from the sun. Voyager 2 was 8.8 billion miles (14.2 billion km) from the sun, on a different trajectory, NASA officials said. [NASA's 10 Greatest Science Missions]

The solar wind's outward flow has not yet diminished to zero where Voyager 2 is exploring, but that may happen as the spacecraft approaches the edge of the bubble in the years ahead, researchers said.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.