Augmented Reality Game Lets Kids Be the Scientists

President Barack Obama may have urged Americans to celebrate science fair winners as if they were Super Bowl champions during his 2011 State of the Union address, but American students still struggle with science. Now, researchers hope to ignite kids' interest in science by drawing them into an activity long loved by children: computer games.

On April 4, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Smithsonian Institution plan to launch a first-of-its-kind "curated game" — funded by the National Science Foundation — that's designed to give middle-school students a peak into the process of science. The game, called "Vanished," is an environmental mystery game with a science-fiction twist, said Scot Osterweil, a game developer and creative director of MIT's Education Arcade. It's also an "augmented reality" game, meaning kids will do real-world experiments and activities that mesh with the fiction of the game.

"It is both a development and a research project," Osterweil told LiveScience. "What we want to see is whether, through this type of activity, kids evince real scientific reasoning."

Collaborative game play

An understanding of science and technology is important for many careers, but there's evidence that America's students aren't keeping pace. One recent national study found that only 30 percent of American eighth-graders achieve proficiency in science as measured by standardized testing.

Osterweil and his colleagues hope to inject some excitement back into science for kids in the middle-school age group. That's an important age, said Francis Eberle, the executive director of the National Science Teachers Association.

"It is a critical grade level for students making determinations about what they do in the future, in terms of courses and whether they pursue more science and mathematics," Eberle, who was not involved in the game development, told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Osterweil and his colleagues won't give away much of the plotline of "Vanished" – it is a mystery game, after all, and no one likes spoilers. They will say that the game draws on the popularity of TV shows such as "CSI" and "Bones," which capture the spirit, if not always the accuracy, of science.

"We want kids to think of science as something you do collaboratively. There's critical thinking involved," said Caitlin Feeley, the project manager of "Vanished" at MIT. "In a lot of ways, science is more like solving a mystery than anything you do in science lab."

Doing science online

Kids who sign up for the eight-week game will be given the outlines of the mystery and asked to collect real-world data – such as the temperature in their backyards at certain times of day – and then enter that data into an online database. An online forum moderated by MIT undergrads will give kids a place to spin hypotheses about the solution to the mystery. (The adult interaction is what makes the game "curated," the researchers said.)

Some challenges will require kids to go to one of 17 participating museums, which are scattered from California to South Carolina, and then share information with players not close to museums. The goal is to make those kids feel like experts and investigators, not just players, Feeley said.

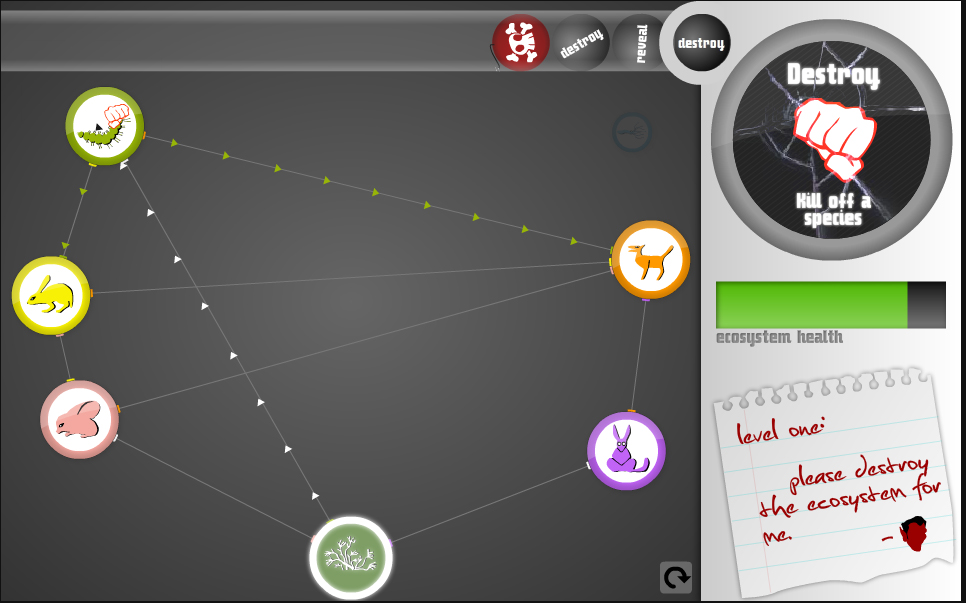

For less-engaged players, "Vanished" features mini-games that don't advance the overall mystery but do teach the environmental themes of the story. The games should help keep kids involved even if they aren't the ones contributing the most work, Osterweil said.

In addition, researchers from the Smithsonian will participate in video conferences with players, helping them refine their hypotheses. Several Smithsonian scientists have also filmed short "day-in-the-life" videos to show the students what scientists do at work.

"It's exciting to see kids get an interest in science through what you can bring them," forensic anthropologist Karin Bruwelheide, of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, told LiveScience. "Having a middle schooler myself, I know that it's an age where a lot of kids drop out of science."

Engagement and effectiveness

The game could be played as a class activity, Osterweil and Feely said, but they designed it as a standalone activity. That's in part because science teachers are already stretched thin, Osterweil said. In addition, most people don't get their science knowledge from school, but from informal activities like reading and museum-going.

The game sounds "very engaging and sophisticated," Eberle said, praising the research aspect of the project. "I think it's clear that games have an engagement component and a motivation component, but we still don't know enough about their effectiveness," he said. "So building that in right up front is terrific. That will be a major contribution to the field."

Kids can sign up for "Vanished" at http://vanished.mit.edu/.

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.