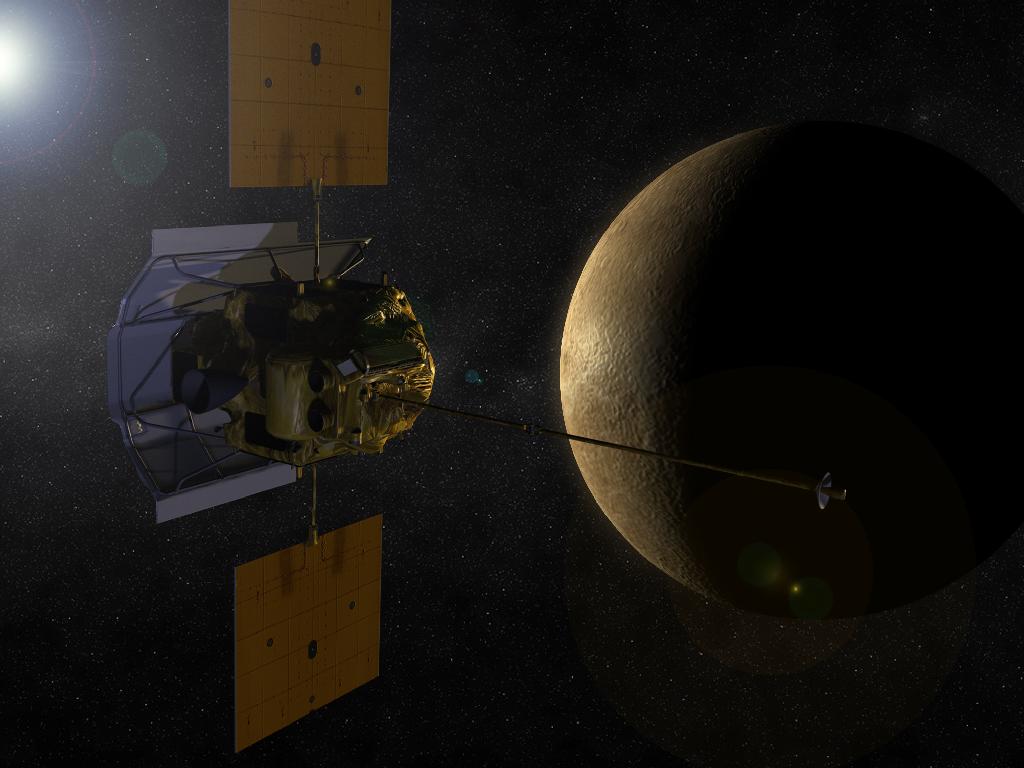

NASA's Messenger probe is poised to make history Thursday (March 17), when it will become the first spacecraft in history to orbit the planet Mercury.

At 8:45 p.m. EDT Thursday (0045 GMT March 18), the Messenger spacecraft will fire its main thruster for 14 minutes to slow itself down enough to enter orbit around Mercury. If all goes well, Messenger is expected to spend the next year studying the solar system's innermost planet, mapping Mercury's surface and investigating its composition and magnetic environment, among other features.

Learning more about Mercury should help scientists better understand how the solar system — and, in particular, the rocky planets Mercury, Mars, Venus and Earth — formed and evolved, researchers said. The Messenger spacecraft has been making its way toward Mercury for more than six years.

"The cruise phase of the Messenger mission has reached the end game," Messenger principal investigator Sean Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, said in a statement. "Orbit insertion is the last hurdle to a new game level, operation of the first spacecraft in orbit about the solar system's innermost planet." [Photos: New Views of Mercury From NASA's Messenger]

A long road to Mercury

The $446 million Messenger (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging) spacecraft launched in August 2004. Over the past 6 1/2 half years, the probe has taken a circuitous, 4.9 billion-mile (7.9 billion-kilometer) route through the inner solar system, completing one flyby of Earth, two flybys of Venus and three flybys of Mercury in the process.

These Mercury close encounters have already produced some amazing photos, returning the first new spacecraft data from the planet since NASA's Mariner 10 mission more than 30 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Messenger hasn't even broken a sweat yet, mission managers said. The probe's real work begins late Thursday, when the probe drops into a highly elliptical orbit around desolate, scorched Mercury.

Messenger is expected to circle the planet once every 12 hours, researchers said. At times, it will come as close as 124 miles (200 km) from the planet's surface; at others, it will drift off to more than 9,300 miles (15,000 km) away on its long, looping circuit.

The spacecraft's science mission will last one Earth year. Because Mercury rotates on its axis so slowly — just once every 176 Earth days — Messenger's mission covers just two Mercury days, researchers said. [Most Enduring Mysteries of Mercury]

Six big questions

Scientists hope Messenger will help them answer six key questions about Mercury. According to NASA officials, they are:

- Why is Mercury so dense? (The tiny planet is far denser than Earth, suggesting that a metal-rich core constitutes at least 60 percent of Mercury's mass — a figure twice as high as that for Venus, Mars or Earth.)

- What is the structure of Mercury's core?

- What is Mercury's geologic history?

- What is the nature of Mercury's magnetic field? (Mercury has a global internal magnetic field, as does Earth; Venus and Mars do not.)

- What are the strange materials at Mercury's poles? (Radar studies have found highly reflective materials inside permanently shadowed craters at the planet's poles. Even though Mercury is so close to the sun — on average, about 2.6 times closer than Earth is — this stuff might be water ice, researchers said.)

- What is Mercury's "atmosphere" like? (The blanket of volatile gases hugging Mercury is so thin and tenuous that the planet technically has an exosphere, not a thick atmosphere like Earth.)

That's a long and ambitious list, but mission scientists are excited that they're just about to begin tackling it.

"The Messenger team is ready and eager for orbital operations to begin," Solomon said.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the Messenger mission to Mercury news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.