Swans: 'Do Our Butts Look Big?'

A population of black-beaked swans known to winter in the United Kingdom is dwindling, and researchers are looking for clues as to why in an unusual spot: the birds' back ends.

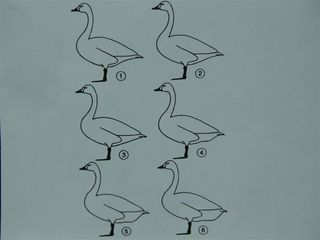

That's because bird butts can signal lots about the animal's diet, according to the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT), a conservation organization that is running the study. To find out whether the birds are getting enough food to sustain them on their annual migration, WWT scientists and volunteers are checking out the swans' behinds, a technique also known as "abdominal profiling." A well-fed bird carries a little extra junk in the trunk, between its legs and tail. In contrast, a scrawny, underfed swan — the kind less likely to survive the journey north — will lack a filled-out booty.

The Bewick's swan spends its winters in Europe and the U.K. and flies to Arctic Russia each spring. Even as other swan populations have stayed stable, Bewick's swan flocks are dwindling. The number of Bewick's swans wintering in Europe dropped 27 percent between 1995 and 2005, from 29,000 to 21,000 individuals, according to WWT.

One possible reason for the species' troubles is a lack of food in their winter forage grounds in the U.K. – thus, the bird body fat checkups, Julia Newth, a WWT researcher, said in a statement. The data analysis isn't complete, Newth said, but early observations suggest the birds are packing on plenty of fat for their long journey. So if these results hold, and scrawny derrieres aren't found, the researchers could rule out lack of food at the wintering grounds.

"We need to do further work to see whether their body conditions have changed over the years, and, if so, whether this is connected with the decline in numbers," Newth said.

Various other factors could be hurting the swan population, including habitat and weather changes at their breeding grounds in Russia, as well as poaching, collisions with power lines and lead poisoning, according to WWT.

"Results from this year's observations will be compared with data collected previously during the ‘80s, ‘90s and last winter," Newth said. "It will help rule out that the reduction in overwintering swans is due to changes in habitat at U.K. wintering sites — and give an indication of how the swans are responding to environmental change."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.