Raise Your Glass: 10 Intoxicating Beer Facts

Beer Basics

If America had an official alcoholic beverage, it would probably be beer. According to the Brewers Association, the overall U.S. beer market was worth $101 billion in 2009. Over 205 million barrels of beer were sold (1 barrel equals 31 gallons of beer). In the same year, there were 1,595 breweries in the U.S. fermenting everything from light lagers to chocolaty stouts.

In that spirit, LiveScience proposes a toast to beer, that sudsy beverage that humans have brewed for millennia.

What's in a glass?

Water, mostly. But also flowers, fungus and grains.

Beer gets much of its flavor from hops, which are vine-grown flowers that look more like mini-pinecones than daisies. The alcohol in beer comes from grain, usually barley, which is malted (or allowed to germinate) and then steeped in water to extract its sugars. Those sugars become a feast for yeast, the tiny, unicellular fungi that thrive on sugars and excrete alcohol.

Yeasts usually get filtered out of commercial beers before they're bottled, but they leave traces (and flavors) behind. A study published in August 2010 in the Journal of Proteome Research found that beers contain a surprising variety of proteins: at least 62, 40 of which come from yeast. These proteins are key in supporting beer's foamy head, the researchers noted.

Top to it!

The hops that give beer both its bitter taste and fruity aroma are also powerful cancer-fighters. Hops are a better source of cell-damage-fighting antioxidants than red wine, green tea and soy products, according to a 2000 study in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. The source is xanthohumol, a tongue twister of a compound found only in hops.

The bad news is that you'd have to drink about 118 gallons (450 liters) of beer a day to see a health benefit from the antioxidants in hops. Eventually, researchers hope to distill that hoppy, anti-cancer goodness down to a pill to help prevent cancer.

Who drank it then ...

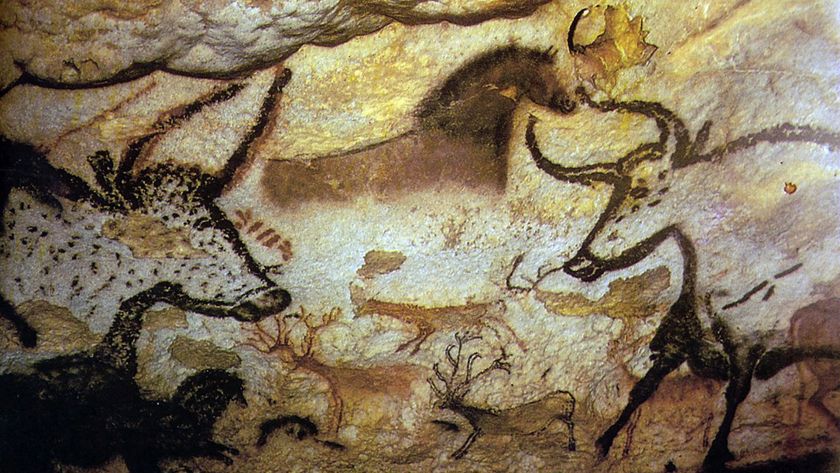

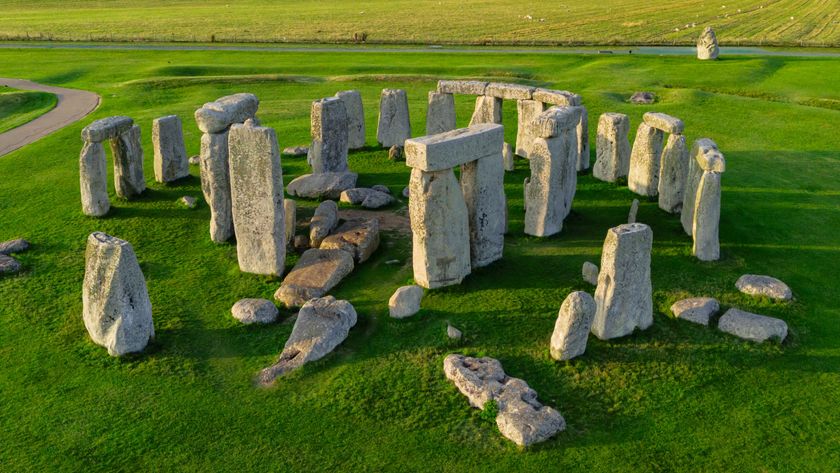

Humans and yeast have been working together for millennia to create tasty brews. As early as the 6th millennium B.C., ancient Sumerians had discovered the art of fermentation. By the 19th century B.C., they were inscribing beer recipes into tablets in the form of a Hymn to Ninkasi, their female deity of beer.

Other cultures around the world developed beer independently, but the job of brewing often went to women. Tenenit, the Egyptian deity of beer, was female, as was the Zulu beer goddess Mbaba Mwana Waresa. A 2005 study found that among the Wari people of ancient Peru, elite women brewed the beer. Centuries later, women dominated the European brewing scene, according to a 1993 article in Yankee Brew News by late beer anthropologist Alan Eames. According to Eames, it wasn't until the late 1700s that beer became a male-dominated drink.

And who drinks it now

Today, beer is the preferred beverage of men, according to data from a July 2010 Gallup poll. Of the 67 percent of U.S. adults who drink alcohol, 54 percent of men named beer as their top alcoholic beverage compared with 27 percent of women. (Liquor was equally preferred by both genders, while women heavily favored wine, a trend largely driven by women over 50.)

Beer is more popular among young people, with half of 18- to 34-year-olds listing it as their top intoxicating beverage. Midwesterners are the top beer-drinkers in the United States, but not by much. Forty-six percent of Midwesterners said beer was their favorite drink, compared with 42 percent of Easterners, 40 percent of Westerners and 37 percent of Southerners.

Alternative uses for beer

Beer isn't only enjoyable to drink. Cooks use beer to flavor barbecue sauce, season bread and moisten grilled chicken.

But that's nothing compared with the use John Milkovisch, a retired railroad upholsterer, put beer (or at least beer cans) to. Starting in 1968, Milkovisch spent 18 years lining the outside of his modest Houston home with flattened beer cans. He strung the lids from the eaves and turned them into chain-link fences.

Milkovisch died in 1988, and his home is now a museum. According to the Beer Can House website, the inspiration for the project was simple.

"Well, I think it might have been the good Lord says 'Nut, it's time for you to build this crazy stuff,'" Milkovisch is quoted as saying. "So here I did, I built it."

Brewers are unwitting yeast geneticists

Like lager? Thank Bavarian brewers from the Middle Ages. Without their accidental genetic tinkering, light crisp lagers might not exist.

According to a 2008 study in the journal Genome Research, lager beer came about when brewers started fermenting ale in the winter. The ale yeast, S. cerevisiae, couldn't ferment well in cold temperatures, so it survived by hybridizing with another yeast, S. bayanus, which grows best in nippy weather. The resulting strain of yeast was S. pastorianus, now used in lagers worldwide.

Light makes beer go bad

Beer that goes bad can ruin a party. Fortunately, science can help you prevent such disasters.

Though many people blame age or prolonged refrigeration for a bad beer's "skunked" taste, it's actually light that spoils the brew. A 2001 study published in Chemistry – A European Journal traced the breakdown of beer to light-sensitive hop compounds called isohumulones. Prolonged exposure to light causes a reaction in which isohumulones become "skunky thiol," so dubbed because it resembles a compound found in skunk glands. Not so refreshing -- which is why beer is normally stored in protective brown or green bottles.

Beer is good for the bones …

While beer is not likely to qualify as a health food anytime soon, it does contain at least one ingredient that's good for you: silicon.

A study released in February 2010 in the Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture revealed that a couple of beers can provide a healthy daily level of silicon, which is important for bone health. Beers high in malted barley and hops had the most silicon, with Pale Ales topping the list. Wheat beers and lagers are less silicon-rich.

... But bad for the head

Of course, beer has its downsides too, the most immediate of which is the dreaded hangover. Alcohol has all sorts of nasty effects on the body — from disrupted sleep to dehydration — that can make you feel terrible the next day.

Hangovers may be nature's way of enforcing moderation in drinking, given that enough alcohol can be deadly. Long-term consequences of drinking too much include liver disease and an increased risk of cancer. According to a 2009 study published in the journal Cancer Detection and Prevention, the more alcohol you drink, the higher your risk of cancer. Heavy drinkers have a risk of esophageal cancer seven times that of teetotalers. Drinking daily also increased the risk of stomach, colon, rectal, liver, pancreas, lung and prostate cancer.

What floats down ...

Observant beer drinkers might notice that when beer is poured into a glass, the bubbles seem to defy the laws of physics, floating down instead of up.

Turns out those people haven't had too much to drink. Beer bubbles really do float downward sometimes, according to a 2004 analysis by Stanford researchers. Because of the drag from the walls of the glass, they found, the beer bubbles float up more easily in the center of the glass. As those bubbles go up, they pull the surrounding liquid to the surface. When the bubbles join the froth, or 'head' of the beer, the liquid begins to pour back down the sides of the glass, dragging smaller bubbles down with it.

The researchers used a super-slow-motion camera to capture the bubbles' descent and figure out the mystery. That’s one way to win a bar bet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.