Oceans May Be Speeding Melt of Greenland's Glaciers

Dynamic layers of warm Atlantic and cold Arctic Ocean waters around Greenland may be speeding the melt of the country's glaciers, researchers find.

"Over the last 15 years or so, the Greenland Ice Sheet has been putting a lot more ice into the ocean," said Fiammetta Straneo of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, in Massachusetts, who has spent years studying the ice-coated country that is currently responsible for about a quarter of worldwide sea level rise.

"We're trying to understand why, as we thought ice sheets changed on much longer timescales, like thousands of years," she told OurAmazingPlanet.

Researchers know that warm air over Greenland melts surface snow and ice, but this process doesn't do enough melting to explain the extent of the glaciers' rapid retreat. The connection between ocean changes — including a warming Atlantic Ocean — and glacier response is "unchartered territory," and may make up the difference between predictions of ice melt and reality, Straneo said.

Fjord flight

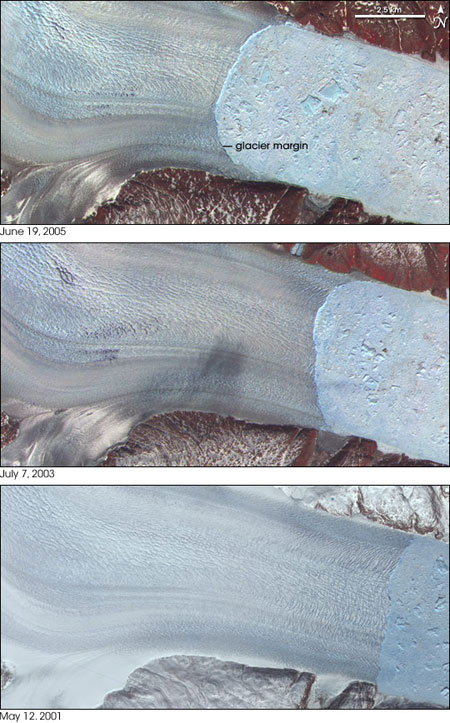

The edge of Helheim Glacier, a major outlet for the Greenland Ice Sheet, is itself a largely unexplored region — and a case in point. Between 2001 and 2005, the ice of the glacier retreated about 5 miles (8 kilometers), with its continued shrinkage nearly doubling in speed.

In August 2009 and March 2010, Straneo and her colleagues flew helicopters over Sermilik Fjord, a 62-mile-long (100 kilometers), 5-mile-wide (8 kilometers) and up to half-mile-thick (900 meters) chunk of ice extending into the ocean at the end of the glacier.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on samples from probes launched into rare patches of open water near where the glacier meets the sea — an area extremely difficult to reach by boat — the researchers discovered that the interplay between glacier ice, freshwater runoff and water from both oceans is far more complex than previously thought.

"We used to think that warm Atlantic water was just carried up, melting the whole vertical face of the glacier," said Straneo. "But we found that with this Arctic water sitting at surface, the melting is really only at the bottom."

Little push, big change

Differences in water densities drive this dynamic, which appears to be deforming the fjord and therefore affecting its stability and the flow of the glacier, according to the report published online this week in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"We now think that small changes — increased warm water reaching the edges, for example — may alter the shape of the glacier as it plunges into the ocean, and this in turn affects the friction that keeps the glacier from running fast," Straneo added. "A little push is driving a big change."

The team also found that the circulation differs between the summer and the winter. Yet current climate models take none of these factors into account.

Sea level rise

Greenland holds enough water to raise sea levels 21 feet. While such a catastrophic melt isn't expected anytime soon, short-term impacts could still be severe as ocean waters continue to warm with climate change.

Further, Straneo suggested the same complex interactions at this fjord are likely playing out in other parts of Greenland, as well as in Chile and Alaska. However, the dynamics of Antarctica's glacier system are different, and perhaps less susceptible to ocean temperature changes.

"This study shows that we really need to know more about how the ocean changes at the edge of these glaciers before we can predict changes to the glaciers," Straneo said. "As we interpret the past or forecast future ice sheet variability and sea level rise, this will greatly impact the answers that we get."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.