Weird Saturn Radio Signals Puzzle Astronomers

Saturn is sending astronomers mixed signals — radio signals, that is.

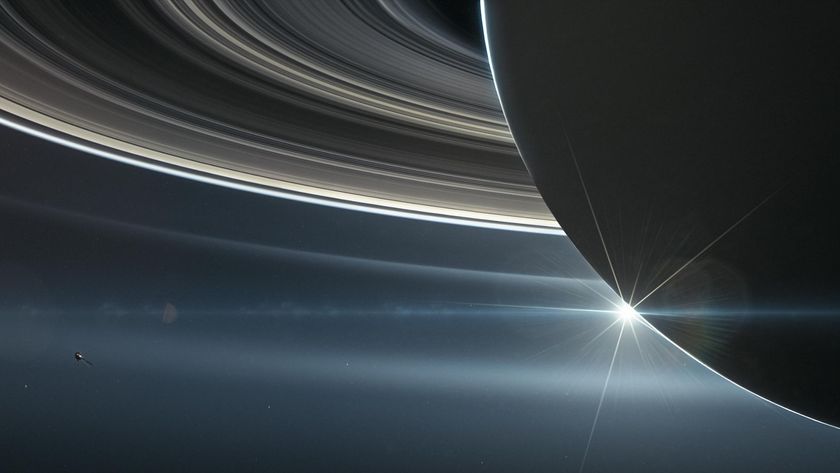

NASA's Cassini spacecraft recently found that the natural radio wave signals coming from the giant planet differ in the northern and southern hemispheres, a split that can affect how scientists measure the length of a Saturn day. But the weirdness doesn't stop there, researchers say.

The signal variations — which are controlled by the planet's rotation — also change dramatically over time, apparently in sync with the Saturnian seasons.

"These data just go to show how weird Saturn is," said Don Gurnett of the University of Iowa, who leads Cassini's radio and plasma wave instrument team, in a statement. "We thought we understood these radio wave patterns at gas giants, since Jupiter was so straightforward. Without Cassini's long stay, scientists wouldn't have understood that the radio emissions from Saturn are so different." [Video: Saturn's Strange Radio Waves]

Saturn gets weirder

Saturn emits natural radio waves known as Saturn Kilometric Radiation, or SKR for short. While these waves are inaudible to human ears, to Cassini they sound a bit like bursts of a spinning air raid siren and vary with each rotation of the planet.

Cassini scientists have converted the varying Saturn radio wave emissions to the human audio range.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Observations of this kind of radio wave pattern at Jupiter allowed scientists to measure that planet's rotation rate, but at Saturn the situation has turned out to be much more complicated, researchers said.

When NASA's Voyager spacecraft visited Saturn in the early 1980s, the planet's SKR emissions indicated the length of one Saturn day was about 10.66 hours. But later, other spacecraft — including the NASA-European Space Agency Ulysses probe and Cassini — found that the radio burst varied by seconds to minutes.

Other Cassini observations showed that the SKR emissions were not even a solo. They are actually a duet — but the planet's two "singers" are out of sync.

Radio waves emanating from near Saturn's north pole had a period of around 10.6 hours, while those coming from around the south pole repeated every 10.8 hours, researchers said. [Photos: Saturn's Rings and Moons]

Then the situation got even weirder.

In December, Gurnett and his team published a paper using Cassini data to show that the southern and northern SKR periods crossed over in March 2010. That is, the southern period decreased steadily and the northern one increased, with the two finally converging at around 10.67 hours last March.

This happened seven months after Saturn's August 2009 spring equinox, when the sun shone directly over the planet's equator. Since the crossover, the pattern has continued, with the period of southern SKR emissions decreasing and that of northern ones increasing, researchers said.

Saturn signal review

Seeing the strange radio wave crossover led the Cassini scientists to review observations from previous Saturn visits. They found similar patterns in the Voyager data from 1980, as well as Ulysses observations taken between 1993 and 2000.

In both cases, the radio emission variations differed from one hemisphere to the other. And both times, the odd radio wave behavior came within a year of Saturnian equinoxes, researchers said.

So what's going on? Cassini scientists don't think the differences in radio wave periods have to do with Saturn's hemispheres actually rotating at different rates.

More likely, the signal changes are caused by variations in high-altitude winds in the northern and southern hemispheres, researchers said. The behavior of Saturn's magnetosphere — the magnetic bubble that surrounds the entire planet — is also likely having an impact, they added.

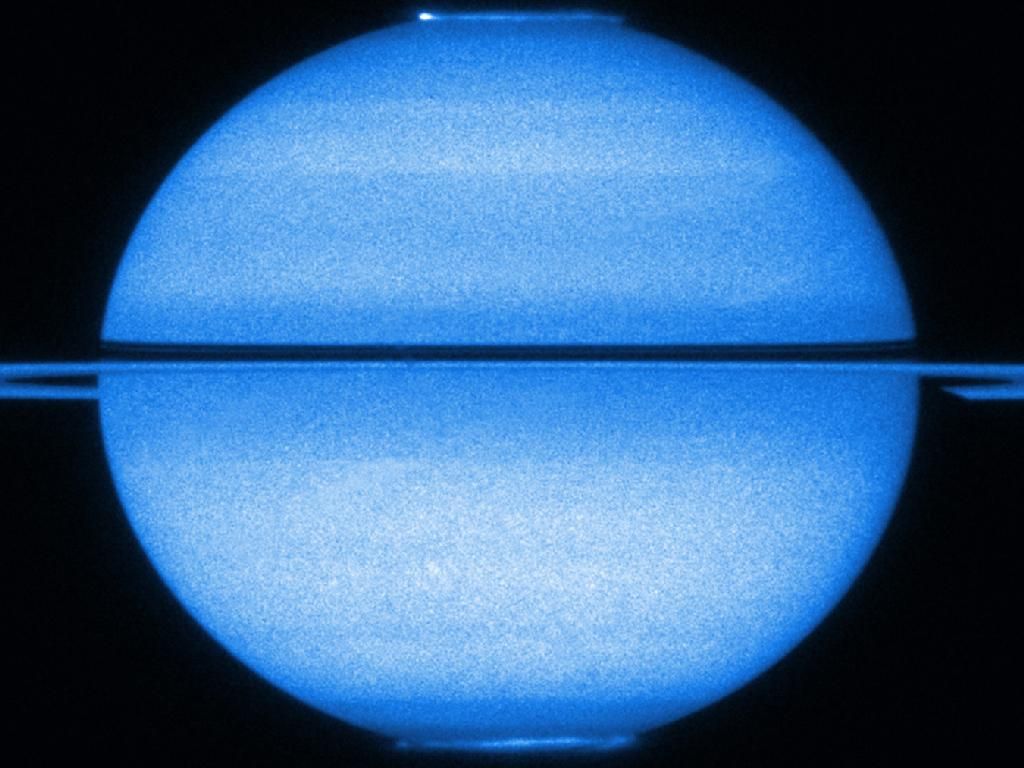

In a different study, researchers using observations from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope found that the northern and southern auroras — light shows caused by the interaction of the solar wind with Saturn's magnetic field — wobbled back and forth in latitude in a pattern matching the SKR variations, researchers said.

And another study showed that Saturn's magnetic field above the planet's two poles varied in time with the aurora and the radio wave emissions.

"The rain of electrons into the atmosphere that produces the auroras also produces the radio emissions and affects the magnetic field, so scientists think that all these variations we see are related to the sun's changing influence on the planet," said Stanley Cowley of the University of Leicester, a Cassini scientist and a co-author on the two recent Saturn magnetic field papers.

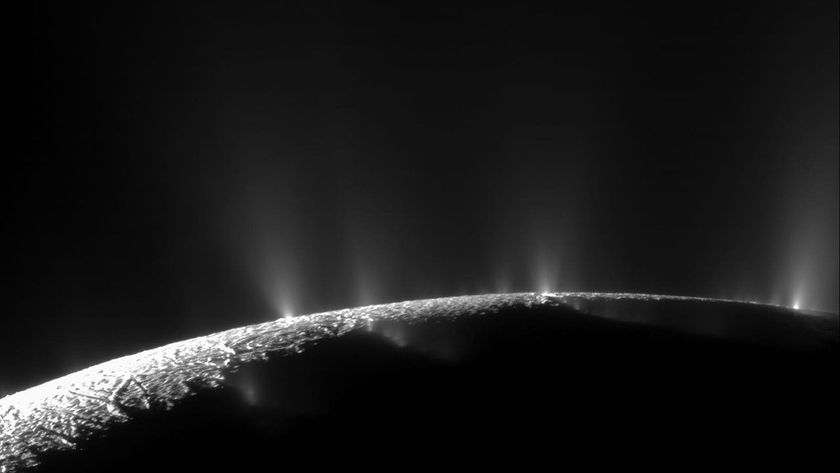

NASA's Cassini spacecraft launched in 1996 and arrived at Saturn in 2004. It also carried the European Space Agency's Huygens lander, which landed on the Saturn moon Titan soon after Cassini arrived in orbit around the ringed planet.

The spacecraft completed its primary mission to explore Saturn, its rings and moons in 2008. Since then, the Cassini mission to Saturn has been extended twice, most recently to 2017.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.