Prehistoric Texans May Have Been First Humans in U.S.

Humans camped by the shores of a small creek in Texas possibly even before the Clovis society, classically regarded as the first human inhabitants of the Americas, settled in the West.

The site, located in central Texas on the bank of Buttermilk Creek, has produced almost 16,000 artifacts, including stone chips and blade-like objects, in soil dating up to 15,500 years old, more than 2,000 years before the first evidence of Clovis culture. Many of the items are flakes from cutting or sharpening of tools, but the research team also found about 50 tools, including several cutting surfaces — including spear points and knives.

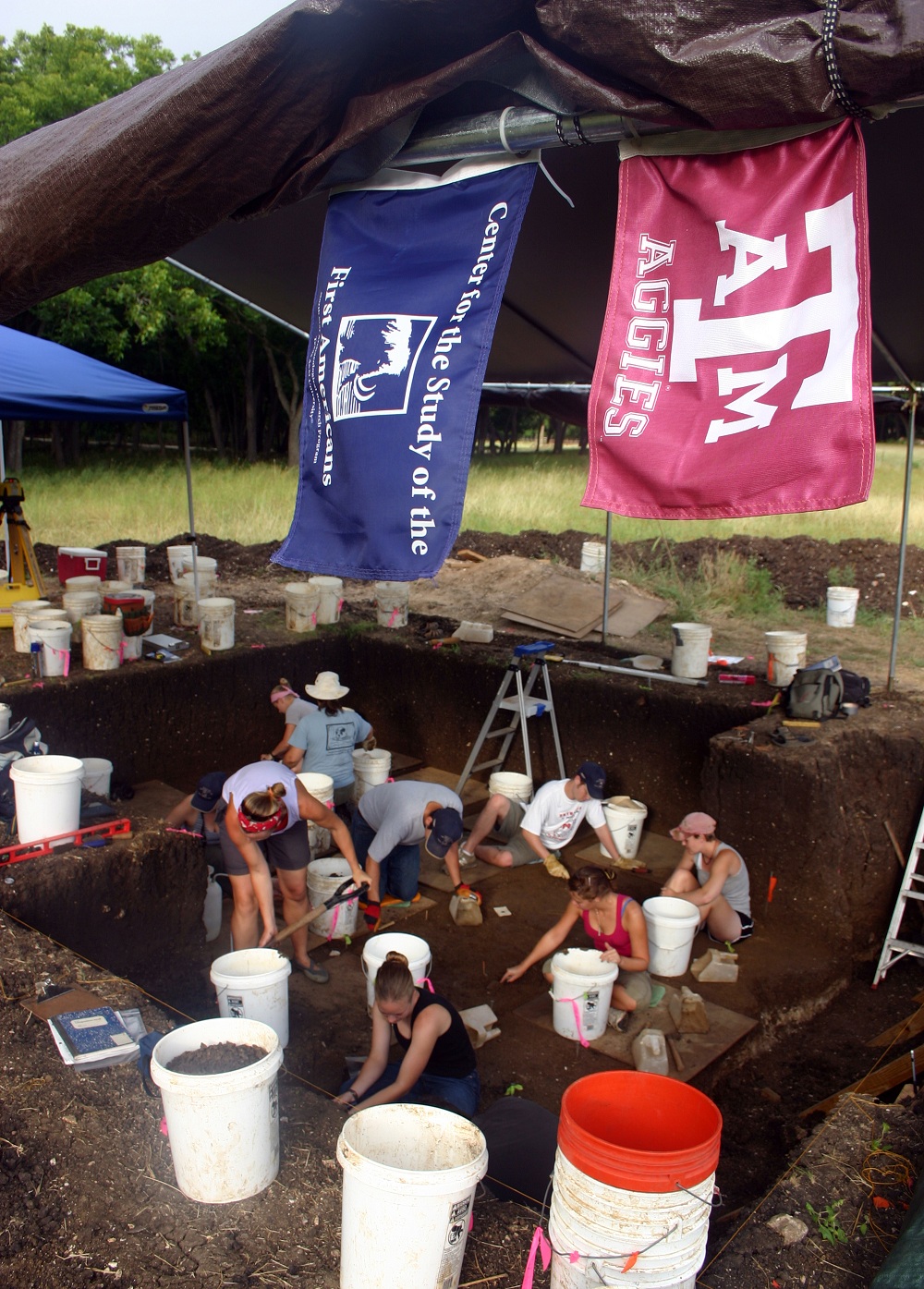

"The tools that we found there indicate that they were camping along the Buttermilk Creek," study researcher Mike Waters, at Texas A&M University, told LiveScience. "This probably would have been a place where they were living and conducting daily activities."

All of the objects were small and light and seem to indicate that the group led a mobile lifestyle, moving from place to place but always returning. From the wear and tear on the artifacts, some seem to have been used for cutting soft materials, like hides, while others may have been used on harder materials, like stone.

The prehistoric humans seem to have used the site for multiple centuries, as the soil where the artifacts were found was dated to between 12,800 and 15,500 years ago. "They would leave the site and come back, and each time leave behind evidence of their activities," Waters said. "They slowly but surely built up these deposits. Dating them shows they range from 15,500 years ago, then just keep going until the Clovis material."

The researchers couldn't date the material with the gold-standard method using carbon-14, since none of the artifacts had organic components, such as plant matter. The team used a different kind of dating on the soil around the artifacts, and some researchers called it into question. Extended excavation of the site could reveal carbon-dateable objects, which would confirm the age of the site.

If the dating is correct, this group would predate the Clovis society, long thought to have colonized the Americas 13,000 years ago, and could have given rise to the Clovis society. These prehistoric human societies are generally defined by the stone tools they used, the size and shape of which changed over time. Clovis used bigger blades and tools than those found at this layer of the Buttermilk site.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The site isn't the first to predate Clovis, though Waters believes his evidence is the clearest yet.

Not everyone agrees with Waters' interpretations of the findings, though. While other researchers don't question that there were probably human populations in America before Clovis, they note the evidence isn't as strong at this site as at some others.

Tom Dillehay, a researcher at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee who wasn't involved in the study, told LiveScience that the ecological conditions at the site, including rain-swept mud and remnants of creek flooding, may have mixed the sediment layers, meaning the Clovis sediments could have been buried on top of the artifacts described by Waters, and therefore been considered more recent. The top layers are very thin.

Gary Haynes, of the University of Nevada, Reno, praised the authors for a "potentially major find" but had many of the same concerns about the research.

"They need to excavate a bigger area of the site before they can draw these kinds of conclusions," Dillehay told LiveScience. "I don't see that the data is there to present the conclusions that they are presenting."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.