Tooth Implant Replaces Impractical Radiation Monitors in Emergencies

As donations and support fly into Japan from around the world, a radiologist at Dartmouth University has offered officials a device he originally designed to help after massive terrorist attacks: a dosimeter that detects radiation exposure from changes in tooth enamel.

Instead of relying on traditional radiation badges to determine how much their wearers have been exposed, “we use a badge that you always carry with you. And that is your teeth,” said the inventor, Harold Swartz.

The machine, which he is hoping will soon be available in a portable, easy-to-use version, could be valuable in triage after a widespread radiation exposure, reducing the burden on medical facilities.

So far, Japanese officials have managed to track the spread of radioactive materials by using badges and Geiger counters. But if large amounts of radiation escape from the plant, either through ground water or vapor, measuring exposure could suddenly pose an enormous challenge.

In most cases, the human body doesn’t keep a record of the abuses it has tolerated, but radiation is unique. Ionizing radiation has such high energy levels that it rips electrons right out of the atoms in the human body, leaving free radicals in the tissue that cause cellular damage and radiation sickness.

Highly organized and dense materials, such as teeth, can capture these free radicals.

“In the case of teeth and bones, they persist for eons,” Swartz said. “It stays so long that people use it for archeological dating.”

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

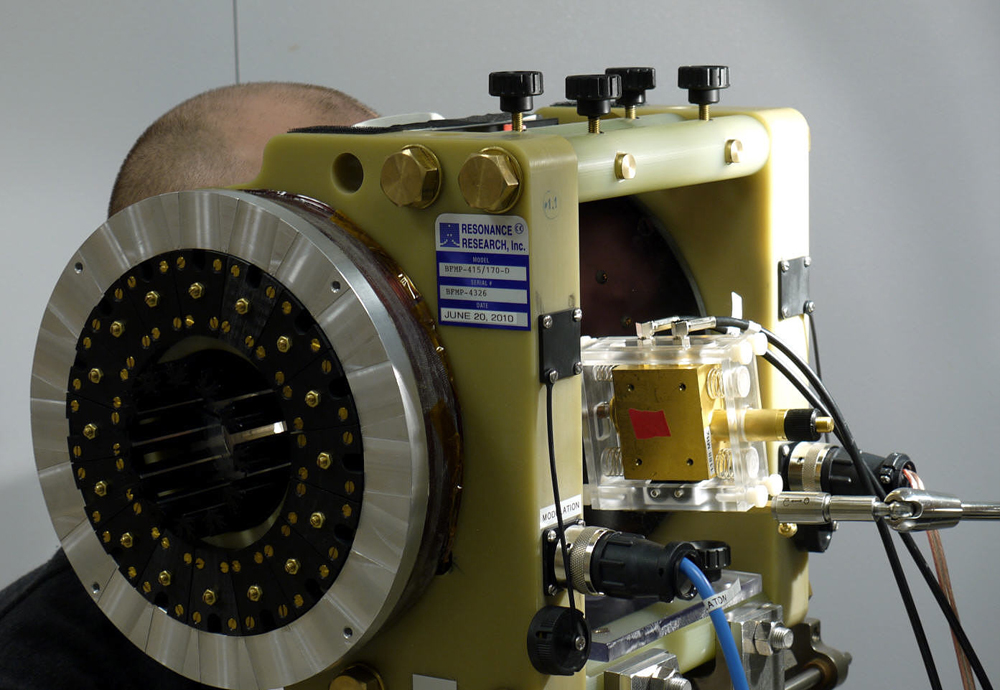

Radiation badges record exposure by measuring changes on a special film, while teeth record it with changes in the enamel. Swartz has simply taken advantage of this fact. His dosimeter uses electron paramagnetic resonance to detect the free radicals in tooth enamel and provide a measurement of all past exposure to ionizing radiation.

The project was funded by DARPA and the National Institutes of Health to prepare for a large-scale terrorist attack. In the event of widespread radiation exposure, the medical system is likely to be flooded by a tide of anxious patients. Sorting out legitimate cases of radiation exposure will be the crucial first task.

Any good triage tool is extremely accurate and easy to use. Swartz spent the last few years testing his dosimeter and will soon begin working with corporate partners to make it portable and user-friendly. When it’s finished, the device has to be so self-explanatory “that a hotel clerk or a house cleaner could operate the machine with a five-minute video,” Swartz said.

In 2009, Swartz gave a version of his dosimeter to Japan to use as a research tool. Last week, he said, the Japanese military contacted him about acquiring another one.

Very few workers have become sick in Japan, nowhere near enough to cripple the medical system. Unless the situation rapidly plunges into despair, there’s no rational reason to begin testing the general population for exposure, Swartz told InnovationNewsDaily.

But there is another, irrational reason to deploy it.

“The answer, of course, is there are real people involved. And real people are not completely rational,” Swartz explained. “The government has a tough job of convincing everybody that they are sincere and accurate and totally open.”

In the midst of the panic and paranoia of crisis, providing quick and easy exposure tests could help reassure the public while fortifying trust in officials. Sometimes, keeping people calm and confident is just as important as keeping them healthy.