25 grisly archaeological discoveries

Disturbing digs

In archeology, bone fragments and other haunting reminders of long-dead people are a given. But some discoveries paint particularly gruesome pictures of past lives and deaths. From decapitated gladiators and vampire burials to ancient toothy tumors and a mummified lung, Live Science has gathered 25 archeological discoveries that give us the creeps.

Decapitated gladiators

A set of skeletons discovered in York, England, belonged to tall men who died before the age of 45. What makes them gruesome is that all of them had also lost their heads. Their heads were buried with them, sometimes on their chests, and sometimes between their legs or feet.

Researchers aren't sure why most of the skeletons at the Driffield Terrace were decapitated. They date to between the second and fourth centuries A.D., when the area was part of the northern Roman Empire. Because most of the skeletons were particularly tall and showed signs of trauma, they may be the bones of gladiators. They might also have been military men. A genetic analysis of seven of the decapitated skeletons found that six hailed from Britain, while one may have come from Lebanon or Syria. [Photos: Headless Gladiator Skeletons]

Evidence of war

About 10,000 years ago, something horrible happened in what is now Kenya. Twenty-seven people — men, women and children — died of trauma. Their bones, discovered in 2012 in the sediments of Lake Turkana, show the marks of blunt weapons like clubs and sharp projectiles like arrows. Archaeologists think that the size of the group indicates ancient warfare rather than a violent domestic dispute. One woman (shown here) was found with both knees broken, hands extended in front of her, prompting speculation that she may have been bound.

Pit of death

A property development project in France uncovered something truly shocking in 2012: A pit, 6.5 feet (2 meters) deep and 5 feet (1.5 m) in diameter, filled to the brim with bones.

Even more sickening, the bones consisted of severed arms and fingers as well as the skeletons of infants, children and adults. Researchers found at least seven upper arms, including one from a young teenager. On top of the amputated limbs, seven bodies had been tossed into the pit, including that of a middle-age man who'd had an arm chopped off and suffered a blow to the head. These bones dated back about 5,335 years.

The bodies (and body parts) most likely were casualties of war, the researchers told Live Science. Some may also have been executed in a sort of brutal Neolithic justice.

Toothy tumor

When Spanish archaeologists unearthed the 1,600-year-old skeleton of a Roman woman, they were surprised at what they found in her pelvis. Peeking out from between her hips was a calcified ball of bone containing four malformed teeth.

This creepy discovery was an ovarian teratoma, a kind of tumor that arises from germ cells. Germ cells are the precursors of human egg cells, so they can form body parts like teeth and bones. The most common teratomas are benign, as was the one in the Roman woman's pelvis. Complications from the tumor could have eventually killed the woman, archaeologists said, but she may never have known the toothy thing was inside of her abdomen.

Polish 'vampire' burials

The real story behind Eastern European vampires is quite possibly creepier than the fictionalized tales of Dracula. Between the 1600s and 1700s in Poland, some people were buried with sickles over their necks or rocks wedged under their chins. These precautions were taken to prevent the dead from rising again as vampires who, locals believed, would return to suck the blood of friends and family.

In 2014, researchers found that the "vampire burials" at Drawkso cemetery in Poland were the bodies of locals who had not died of trauma. They were likely victims of a cholera epidemic that would have felled them rapidly, the researchers told Live Science.

Remnants of a witch hunt

Sometimes an archaeology discovery doesn't need to involve bones to be disturbing. A 15th-century church in Aberdeen, Scotland, contains an artifact like that. The chapel contained a stone pillar set with an iron ring, which may have been used to restrain accused witches in 1597.

Aberdeen hosted a series of witch trials that year known as the "Great Witch Hunt." Around 400 people were tried, and approximately 200 executed in an eight-month period. The deaths were grisly. One of the most famous cases, Jane Wishart, was convicted along with her son Thomas Leyis. Both were strangled and then burned.

Civil War massacre

An attempt to expand the library at Durham University in northeast England turned into a discovery of 17th-century pain and suffering.

Archaeologists excavating in advance of construction discovered two mass graves containing 1,700 skeletons dating back to the mid-1600s. The skeletons are probably the remains of Scottish prisoners of war taken captive during the Third English Civil War, a battle between Parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell and Royalists loyal to King Charles II.

The skeletons belonged to men between the ages of 13 and 25, suggesting that they were military men. They showed few signs of trauma and probably died of disease while imprisoned, only to be thrown into anonymous mass graves.

"These are ordinary soldiers from the Scots army, probably raised from the lowlands of Scotland, some highlanders, and up into the northeast of Scotland, whose names we don’t have," said Pam Graves, a senior lecturer at Durham University. "We know the names of contemporary officers, but so rarely do we ever know the names of ordinary soldiers."

Mummified lung

Whole-body mummies are a little creepy. But when you open a sarcophagus and find nothing but a skeleton and a single, leathery lung … well, you've crossed into some pretty spooky territory.

Archaeologists experienced just that when they opened a stone sarcophagus in the Basilica of St. Denis in Paris in 1959. The remains belonged to a queen named Arnegunde who lived between about A.D. 515 and 580.

For a long time, it was a total mystery why Arnegunde's body had decomposed while her lung became mummified. In April 2016, though, researchers reported at a conference in Germany that they'd figured it out. Arnegunde's lung showed chemical traces of plant compounds, as well as high levels of copper. It's likely that after Arnegunde's death, embalming fluid made of plants and spices was injected down her throat, landing in her lung. The queen was interred wearing a copper alloy belt. Copper has antimicrobial properties, so the combination of embalming herbs and metal likely preserved the single organ.

Shackled skeletons

Their necks flexed and jaws gaping, dozens of skeletons peer up from an ancient mass grave near Athens. Their blank expressions aren't what make this discovery grisly: It's that many of the skeletons still wear shackles.

The skeletons — there are 80 in the mass grave, 36 of which have iron shackles around their wrists — belonged to prisoners who died between around 650 B.C. and 625 B.C., archaeologists say.

Historical records tell of an ancient coup in 632 B.C. that could explain the bodies. The Olympic champion Cylon attempted to take over Athens and failed. The bodies could be those of his executed followers, archaeologists said, though that interpretation is by no means certain.

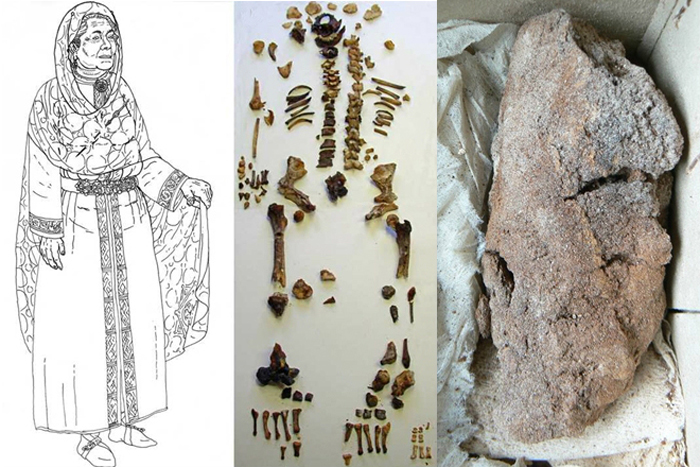

Strange romance

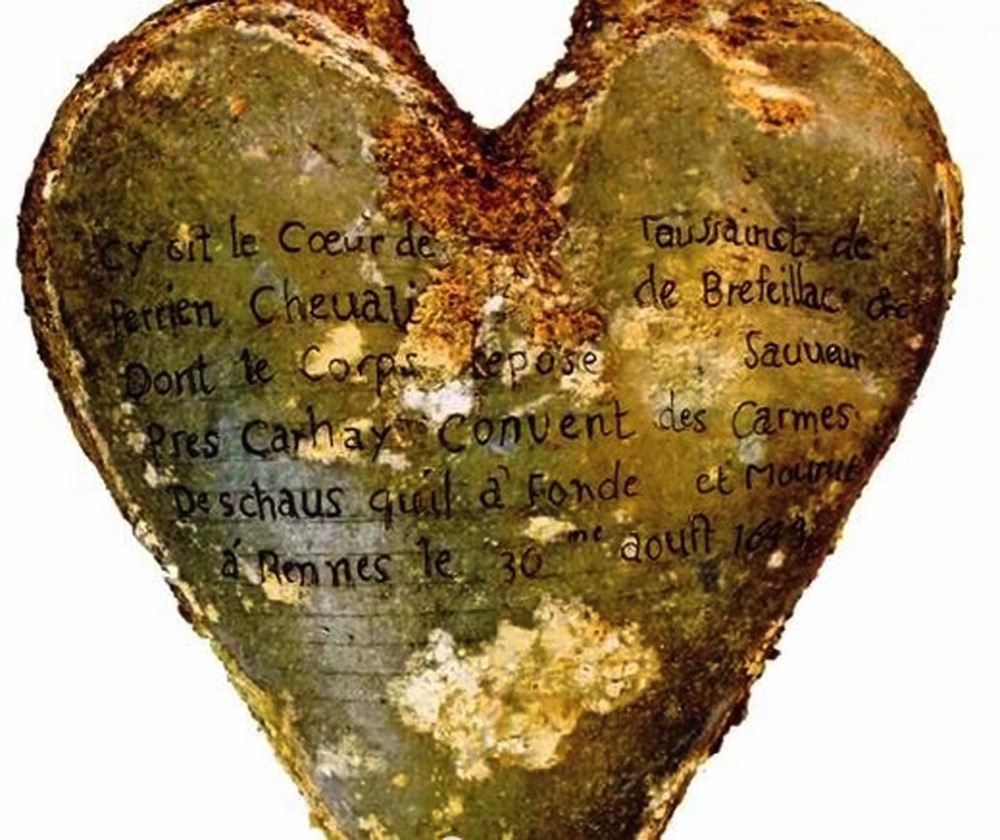

True love was forever for Louise de Quengo, the Lady of Brefeillac. The widow died in 1656 and was interred with a rather alarming trinket: the heart of her husband.

Toussaint Perrien, Knight of Brefeillac, died in 1649. As was sometimes done at the time, his heart was removed, embalmed and put into a lead urn.

"It was common during that time period to be buried with the heart of a husband or wife," Fatima-Zohra Mokrane, a radiologist at Rangueil Hospital at the University Hospital of Toulouse in France, said in a statement. "It's a very romantic aspect to the burials."

Mokrane and colleagues used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) to study Perrien's heart as well as four others from elite graves at the Convent of the Jacobins in northwestern France. The organs were so well preserved that researchers could still see buildup of plaque on many of the arteries.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.