Bizarre Vortex on Venus Changes Shape Every Day

A giant vortex at the south pole of Venus is actually a shape-shifter that changes form at least once a day, at times bizarrely taking on the appearance of a giant letter "S" or the number "8," a new study reveals.

Venus, the second closest planet to the sun, possesses giant, hot and essentially permanent vortexes of clouds whirling fast at its poles. These result from how Venus' atmosphere circulates much faster than any other rocky planet's in the solar system — the cloud-level atmosphere of Venus on average spins 60 times faster than the planet's surface.

The vortexes cannot really be called storms, as scientists have seen neither rain nor lightning in them.

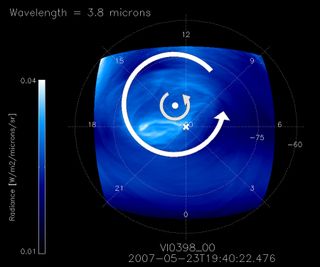

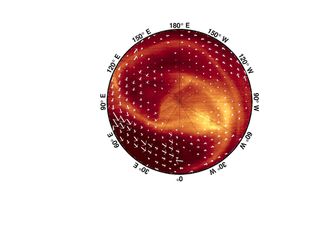

Past images suggested the roughly 1,200-mile-wide (2,000-kilometer) southern polar vortex was only a spinning oval shape. However, new infrared pictures from the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) on the European Space Agency's Venus Express mission revealed far more detail than past images, showing that the vortex's internal structure changes shape at least every 24 hours. [Most Extreme Planet Facts]

"Filaments swirl around one or two bright — that is, warmer — centers," researcher David Luz, a planetary scientist at the University of Lisbon, told SPACE.com. "Sometimes the shape looks like an S or an 8, sometimes it shows three bright centers, but mostly it's irregular."

The vortex is not poised directly over the south pole, but instead its center is consistently located approximately three degrees of latitude away, and it drifts around the pole, completing a circuit every five to 10 days.

These findings suggest the atmospheric dynamics at Venus' southern pole are more complex than scientists thought. They suspect the vortexes are fed by air descending from currents circulating along the meridians over the poles, and the fact the southern vortex drifts suggest the point of maximum downwelling is also wandering. [Infographic: Inside the Planet Venus]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a change in our understanding that general circulation models of Venus will need to take into account," Luz said.

The researchers suspect the vortex at Venus' north pole acts similarly, "but for the moment we don't know, because Venus Express' highly elliptical orbit brings it too close to the north pole, making it impossible to do similar imaging studies," Luz said. "We can see only a very small region."

Europe's Venus Express orbiter has been studying Venus since it arrived in 2006.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (April 7) in the journal Science.

Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.