Boneworms Gnawed on Ancient Reptile Corpses

Bone-gnawing worms that feast on whale carcasses at the bottom of the ocean may be far more ancient than scientists previously thought, scavenging corpses in the abyss long before mammals ever began living at sea.

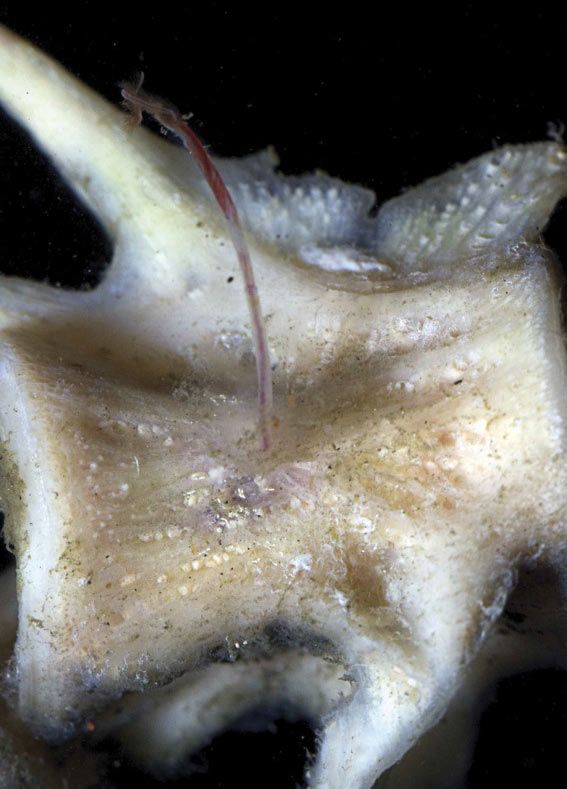

Marine boneworms, known as Osedax, were first discovered in 2002 off the coast of California in an underwater valley called the Monterey Submarine Canyon. These eyeless, mouthless creatures feed by digging rootlike structures into bone, with symbiotic bacteria helping to release nutrients from the skeletons that they can then absorb.

These worms have only been found on the cadavers of sunken whales or other mammals, suggesting that Osedax is a whalebone specialist. To investigate this notion, scientists deployed bones of tuna, cow and other animals in wire cages placed about 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) deep in the Monterey Canyon for five months. The bones were placed next to the carcass of a blue whale. [Image of female Osedax worm]

The researchers found that three Osedax species known to live off whalebone were consuming the fish and cow bones.

"The results allowed us to clearly show that Osedax are not whalebone specialists and are in fact generalists on vertebrate bones," researcher Greg Rouse, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, told LiveScience.

Past research had suggested that boneworms may have evolved 75 million to 130 million years ago in the Cretaceous period, before the end of the age of dinosaurs and well before the origin of whales and other marine mammals. These creatures might have first dined on the bones of fish, turtles, birds and now-extinct marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs.

"Establishing that the boneworms can in fact eat fishbones — and big fish were plentiful in the Cretaceous — means that the Cretaceous origin of Osedax is possible," Rouse said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers had also put shark cartilage in the cages, but these had disintegrated by the time they recovered the cages, making it inconclusive as to whether boneworms might live off shark remains as well.

"We have new, larger shark vertebrae and jaws submerged at present," Rouse said.

The scientists detailed their findings April 13 in the journal Biology Letters.

For more science news, follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience.