28 Devastating Infectious Diseases

Contagious diseases have shaped human history and they remain with us today. As the new coronavirus spreads across mainland China and elsewhere around the globe, such infectious diseases are top of mind for many of us. Here's a look at some of the worst of these infections, from ebola and dengue to the more recent SARS, the new coronavirus and Zika virus.

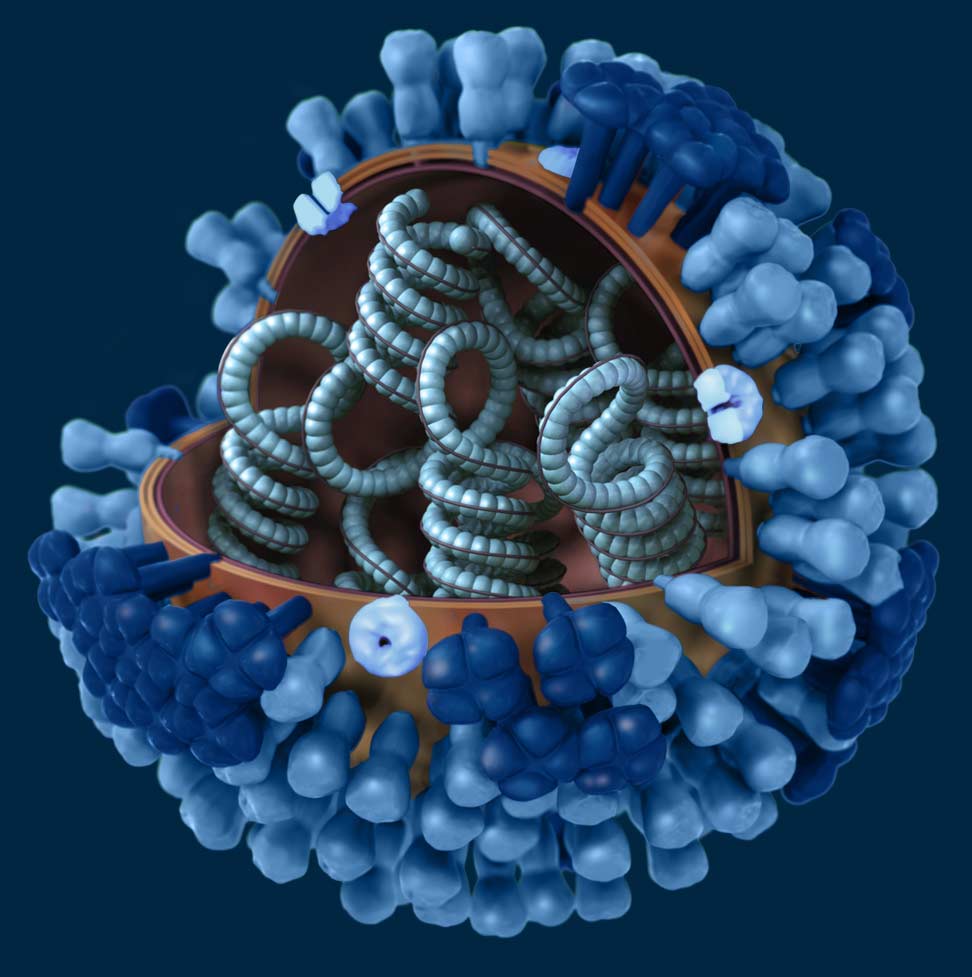

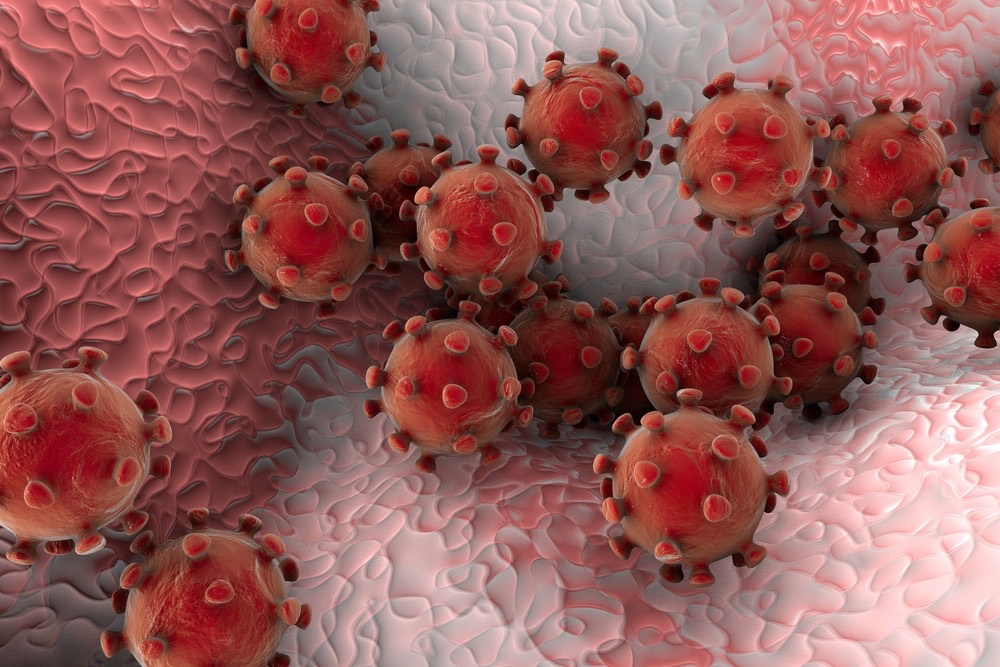

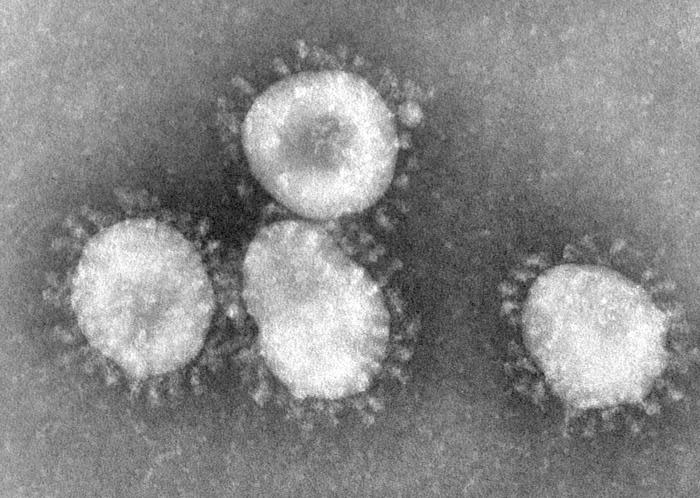

The new coronavirus

The 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is a new strain of coronavirus that first appeared in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Though it was only just discovered, 2019-nCoV has already spread rapidly in China and around the world. As of Feb. 10, 2020, the virus has led to more than 40,000 illnesses and 900 deaths in China, as well as more than 400 illnesses and two deaths outside of mainland China. (The vast majority of cases and deaths have occurred in Hubei Province, where Wuhan is located.)

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that cause respiratory illnesses. This family includes the viruses that cause SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome).

Because 2019-nCoV is so new, many unknowns remain about the virus, including exactly how easily it spreads, how deadly it is and whether it will cause a global pandemic. (The World Health Organization has declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak a "public health emergency of international concern," but has not yet declared it a pandemic.)

Studies suggest 2019-nCoV likely originated in bats, but made it's "jump" to people through a yet-to-be-identified animal, which acted as a bridge between bats and humans.

Smallpox

Scientists think that smallpox, which causes skin lesions, emerged about 3,000 years ago in India or Egypt, before sweeping across the globe. The Variola virus, which causes smallpox, killed as many as a third of those it infected and left others scarred and blinded, according to the World Health Organization.

A photo taken in 1975 shows the village cemetery in the Bangladesh countryside where smallpox victims were buried. The disease is believed to have killed 46 percent of its victims at a hospital in the Dacca, Bangladesh, ravaging the country for centuries.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1980, the WHO declared the disease officially eradicated, after a decade-long vaccination campaign. The last remaining samples of the virus are being held in facilities in the United States and Russia.

Plague

Unlike smallpox, this ancient killer is still with us. Caused by a bacterium carried by fleas, plague has been blamed for decimating societies including 14th-century Europe during the Black Death, when it wiped out roughly a third of the population, including in Basel, Switzerland, depicted in this painting from 1349. The disease comes in three forms, but the best known is bubonic plague, which is marked by buboes, or painfully swollen lymph nodes. Though antibiotics developed in the 1940s can treat the disease, in those who are left untreated, plague can have a fatality rate of 50% to 60%, the WHO said.

Malaria

Although it is preventable and curable, malaria has devastated parts of Africa, where the disease accounts for 20 percent of all childhood deaths, according to the World Health Organization. It is present on other continents as well. A parasite carried by blood-sucking mosquitoes causes the disease, which is first characterized by fever, chills and flu-like symptoms before progressing on to more serious complications. By 1951, the disease was eliminated from the U.S. with the help of the pesticide DDT. A subsequent WHO campaign to eradicate malaria was successful only in some places, and the goal was downgraded to reducing transmission of disease, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The WHO has distributed so-called long-lasting insecticidal nets in order to reduce bites from malaria-carrying mosquitoes, including in Cambodia (shown in image).

Influenza

A seasonal, respiratory infection, flu is responsible for about 3 million to 5 million cases of severe illness, and about 250,000 to 500,000 deaths a year across the globe, according to the World Health Organization.

Periodically, however, the viral infection becomes much more devastating: A pandemic in 1918 killed about 50 million people worldwide. As became apparent from "swine flu" and "bird flu" scares in recent years, some influenza viruses can jump between species.

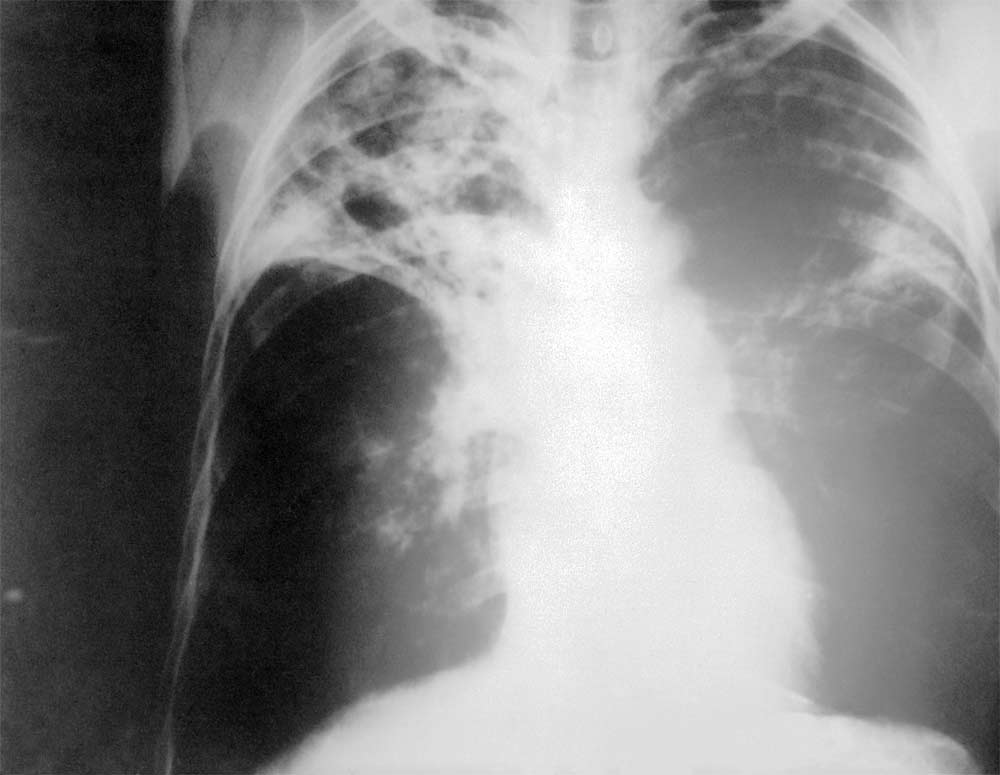

Tuberculosis

Potentially fatal, tuberculosis or "TB" is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which usually attacks the lungs and causes the signature bloody coughs. In patients suffering from an advanced stage of TB, you can see the effects in a lung X-ray (shown in image). ,

The bacterium does not make everyone it infects sick, and up to one-third of the world's population currently carries the bacterium without showing symptoms. And among people infected with TB (but not HIV), 5% to 10% become sick or infectious at some time during their lifetimes.

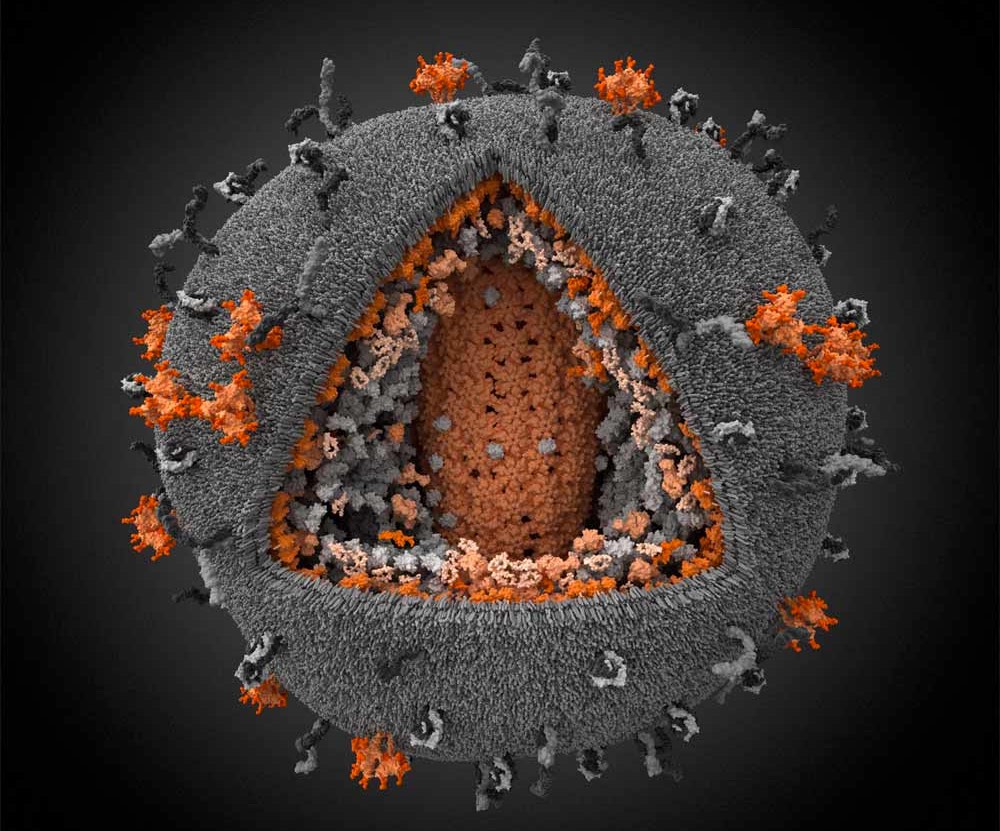

HIV/AIDS

At the end of 2018, about 37.9 million people were living with a Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection worldwide, with 25.7 million of those individuals in Africa. About 770,000 people worldwide died from HIV/AIDS in 2018; 49,000 of those deaths were in the Americas, according to the WHO.

While many of the worst offenders on this disease list have a long-standing relationship with humans, HIV is a recent arrival. HIV's decimating effect on certain immune system cells was first documented in 1981. By destroying part of the immune system, HIV leaves its victims vulnerable to all sorts of opportunistic diseases. It is believed to have emerged from Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), which infects apes and monkeys.

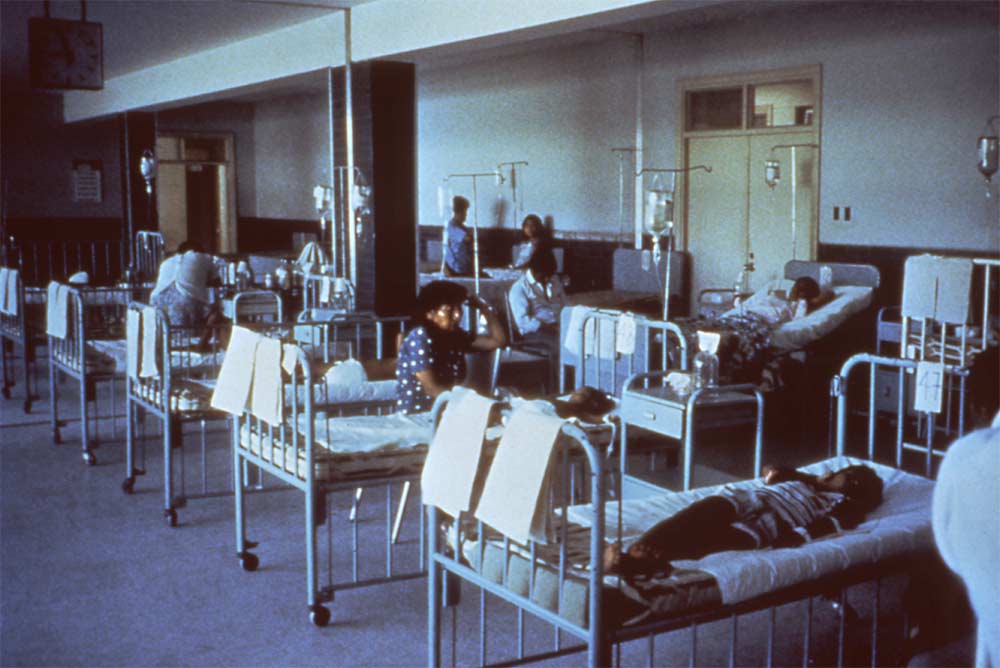

Cholera

Cholera causes acute diarrhea that if left untreated can kill within hours. People catch the disease by eating or drinking substances containing the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria tend to contaminate food and water through infected feces. Since it can take 12 hours to 5 days to show symptoms, people can unwittingly spread the disease through their feces. Thanks to improved sanitation, cases of cholera have been rare in industrialized nations for the last 100 years, but worldwide it kills between 21,000 and 143,000 individuals every year, the WHO estimates.

During the 19th century, however, cholera spread from its home in India, causing six pandemics that killed millions of people on all continents, according to the World Health Organization. During a cholera epidemic in Peru in 1992, a hospital waiting room (shown in image) was converted to an emergency cholera ward.

More recently, a cholera outbreak in Haiti, which began after that country's devastating 2010 earthquake, had sickened more than 810000 people and killed nearly 9,000, according to a report published in 2018 in The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Rabies

No longer a significant threat in the United States, rabies is still a deadly problem in other areas of the world. Rabies causes "tens of thousands" of deaths every year in countries in Africa and Asia, according to the WHO. Approximately two people die yearly in the U.S. from the disease, which is transmitted to humans through the saliva of infected animals, particularly dogs.

The initial symptoms of rabies can be hard to detect in humans, as they mimic that of the flu and include general weakness, discomfort and fever. But as the disease progresses, patients may experience delirium, abnormal behavior, hallucinations and insomnia, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). To date, fewer than 10 people who have contracted rabies and started to exhibit symptoms have survived.

However, a rabies vaccine does exist and is usually very effective in both preventing infection with the virus and treating infected individuals before they begin to show symptoms.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia might not conjure up the same dread as diseases like rabies or smallpox, but this lung infection can be deadly, especially for those older than 65 or younger than 5.

The disease can be caused by bacteria, a virus or a combination of both, according to Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious-disease specialist and a senior associate at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's Center for Health Security. A person can also get pneumonia from a fungal infection, parasites or reactions to certain medicines, Adalja told Live Science in September 2016.

In 2017, there were 49,157 deaths from pneumonia in the United States, according to the CDC.

Infectious diarrhea

Rotavirus, the most common cause of viral gastroenteritis (inflammation of the stomach and intestines), is a diarrheal disease that can be deadly. In 2013, rotavirus killed 215,000 children under the age of 5 globally, according to the WHO. About 22 percent of those deaths occurred in India alone; and overall most of the deaths occur in children living in low-income countries.

The virus causes dehydration, brought upon by severe, watery diarrhea and vomiting. There are four rotavirus vaccines that are considered highly effective at preventing the disease, the WHO says.

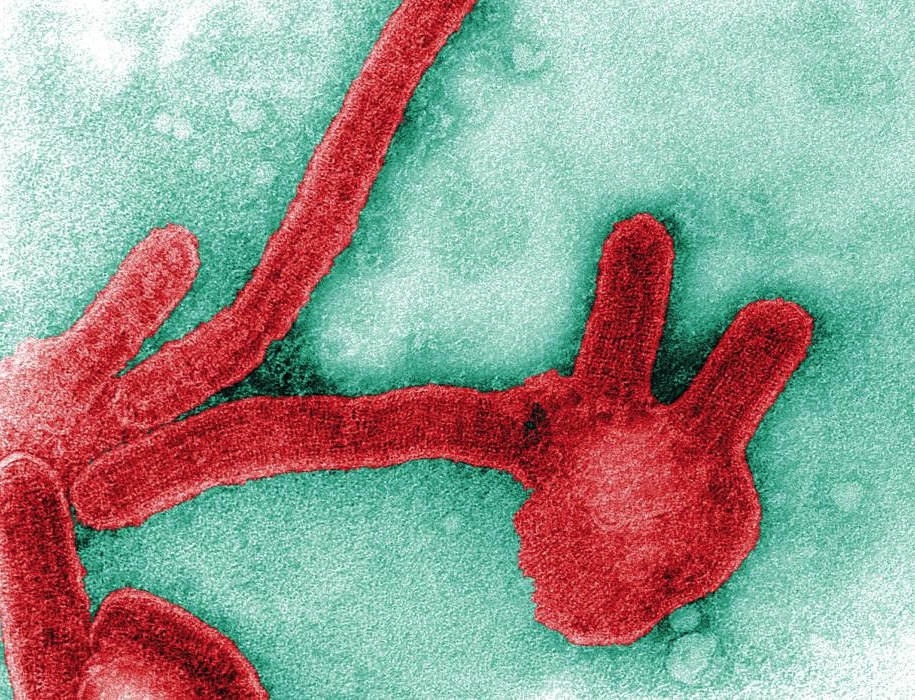

Ebola

Though rare, Ebola virus disease (EVD) is an often fatal infection caused by one of the five strains of the Ebola virus. The virus spreads very rapidly, overcoming the body's immune response and causing fever, muscle pain, headaches, weakness, diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Some who contract Ebola also bleed from the nose and mouth in the late stages of the disease — a condition known as hemorrhagic syndrome.

The Ebola virus is spread from person to person through bodily fluids, and a healthy person can contract the virus by coming into contact with an infected person's blood or secretions or by touching surfaces (like clothing or bedding) containing these fluids.

The largest outbreak of Ebola began in West Africa in 2014. When the outbreak ended in 2016, approximately 11,325 people had died in the outbreak, with 28,652 suspected and confirmed cases of the virus reported, according to the CDC. In August 2018, the Democratic Republic of Congo announced an outbreak of Ebola in its northern province of Kivu. That outbreak, which has infected 3,428 people and killed 2,246 as of February 2020, is still ongoing. A vaccination for close contacts of Ebola patients, called rVSV-ZEBOV, was approved in 2019.

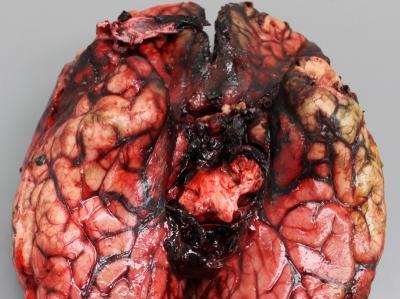

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Its name is not the only complicated thing about variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, or vCJD. This rare and fatal disease is, as its name implies, a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). It's classified as a Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE) — transmissible because it can be spread from cattle to humans and spongiform because it causes a characteristic "spongy" degeneration of brain tissue.

Humans can get vCJD when they eat beef from cows with Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), a disease similar to vCJD that occurs in cattle. Between 1996 and March 2011, approximately 225 cases of vCJD were reported in the United Kingdom and several other countries. Before 1996, scientists didn't know that people could acquire CJD from eating meat contaminated with BSE. Most people who had the disease prior to then acquired it sporadically or because of a particular gene mutation linked to the disease. And about 5 percent of all reported cases resulted from accidental transmission of the disease via contaminated surgical equipment or certain eye and brain tissue transplants.

Individuals infected with vCJD tend to be younger than those infected with CJD. The median age of people with vCJD is 28, whereas that for CJD patients is 68, according to the WHO. Those with the variant version of the disease tend to exhibit psychiatric symptoms, including depression, apathy or anxiety.

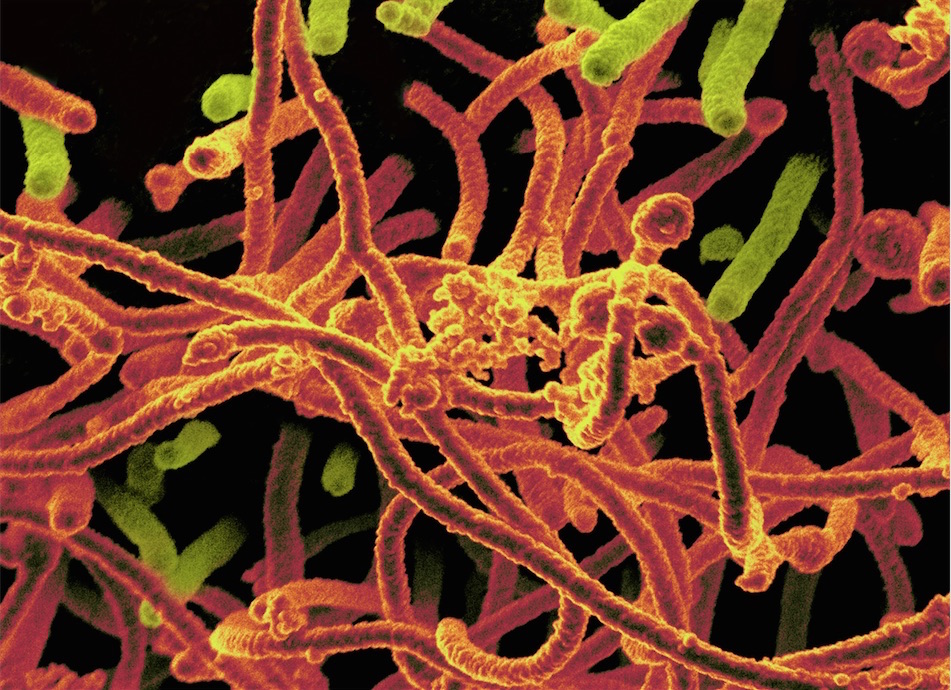

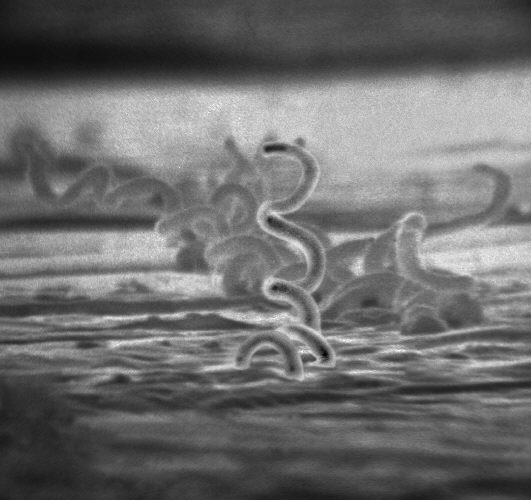

Marburg

Marburg virus belongs to the Filovirus family of viruses, whose defining characteristic are the filamentous shapes of the viral particles. The disease it causes, Marburg virus disease (MVD), is spread from person to person through bodily fluids, much like Ebola. Marburg virus has other things in common with Ebola, as well. It's transferred to humans by fruit bats belonging to the Pteropodidae family, and it can cause viral hemorrhagic fever in some patients.

Marburg virus was first identified in Germany in 1967 after lab workers who had handled infected monkeys imported from Uganda became sick with the virus, according to the WHO. Monkeys, like humans, can be infected with Marburg virus. Fruit bats, however, aren’t sickened by the Marburg virus (or the Ebola virus); they are simply reservoirs or hosts of the virus.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)

As if bat-borne diseases like Ebola and Marburg weren't enough, it turns out the flying mammals are also host to another deadly disease: Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, a viral respiratory disease that was first identified in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. However, though MERs originated in bats, its major reservoir in the Middle East is likely dromedary camels, according to the WHO.

The MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is closely related to SARS and the 2019-ncOv coronavirus currently spreading in China. People who contract MERS develop severe respiratory illness, including fever, cough and shortness of breath. As of 2020, 2,494 cases of the illness had been reported, mostly in Saudi Arabia. About 34% of those who contracted the illness died, according to the WHO.

Dengue

Mosquito-borne viruses — of which dengue is one of many — kill an estimated 50,000 people worldwide every year, according to the WHO and the CDC. (Malaria isn't included in that estimate because it's caused by a parasite, not a virus.)

Dengue (pronounced den' gee) is a disease that can be caused by one of four related viruses: DENV 1, DENV 2, DENV 3 and DENV 4. Mosquitos — usually the species Aedes aegypti (shown here), but sometimes A. albopictus — spread the disease from one person to the next. It's not possible for people to catch dengue from one another. People with the disease typically experience flu-like symptoms. Sometimes the virus leads to a potentially lethal complication known as "severe dengue" or dengue hemorrhagic fever, with symptoms that include fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, bleeding and trouble breathing, according to the WHO.

Yellow fever

Like dengue, yellow fever is a member of the Flavivirus family, and it spreads from one person to the next by mosquitos. The disease gets its name from a symptom experienced by a small percentage of infected patients: jaundice, or yellowing of the skin and eyes.

However, most people who contract the virus never develop jaundice or any other severe symptoms. The small percentage of patients who do develop such symptoms are those who enter a second, more toxic, phase of the disease that affects their body systems, including the liver and kidneys. Half of the patients who enter the toxic phase of yellow fever die within 7 to 10 days, according to the WHO.

Luckily for those living and traveling in one of the 47 countries in Central America, South America and Africa where yellow fever is endemic, there is a highly effective vaccine against the disease. That was not the case in the 17th century, when yellow fever was first transported to North America and Europe, where it caused huge outbreaks and, in some cases, decimated populations, according to the WHO.

Hantaviruses

Hantaviruses are spread to humans by rodents, particularly mice and rats. People can become infected with a hantavirus if they come into direct contact with the bodily secretions of these animals or if they breathe in virus-carrying particles from those secretions that have become aerosolized.

The Sin Nombre hantavirus was first identified in the U.S. in 1993 after a mysterious disease killed several young people in the Four Corners region of the Southwest. Half of the 24 patients initially infected with the Sin Nombre virus died from the disease — a severe respiratory infection known as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, or HPS.

Outside of the U.S. — in Asia, Europe and some parts of Central and South America — hantaviruses can cause another severe illness, known as hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, or HFRS. The initial symptoms of this disease are similar to those of HPS and include fever, vomiting and dizziness; but HFRS can also cause hemorrhaging and kidney failure.

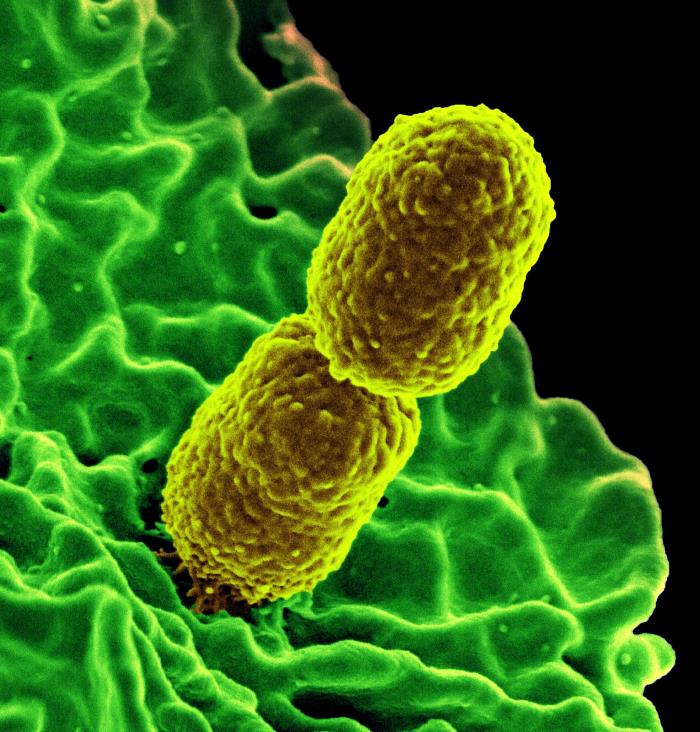

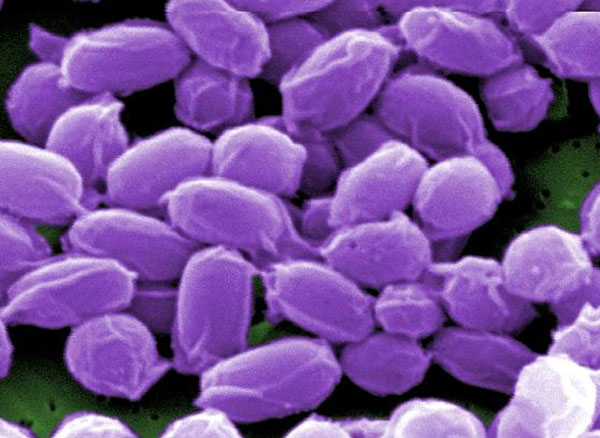

Anthrax

You might be familiar with anthrax from the anthrax attacks in September 2001 in the U.S., which killed five people and sickened 17, and which collectively are considered the worst biological attack in U.S. history.

You might be familiar with anthrax from the anthrax attacks in September 2001 in the U.S., which killed five people and sickened 17, and which collectively are considered the worst biological attack in U.S. history.

Anthrax is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, which lives in soil and usually infects wild and domestic animals, such as goats, cattle and sheep. Humans usually get the disease when they handle infected livestock or animal products. Though you can get anthrax when bacteria spores enter your skin, those who work with animal hides or wool that may be infected with anthrax are also susceptible to inhaling B. anthracis. This pulmonary method of infection with the disease is more lethal, with 92 percent of reported cases resulting in death.

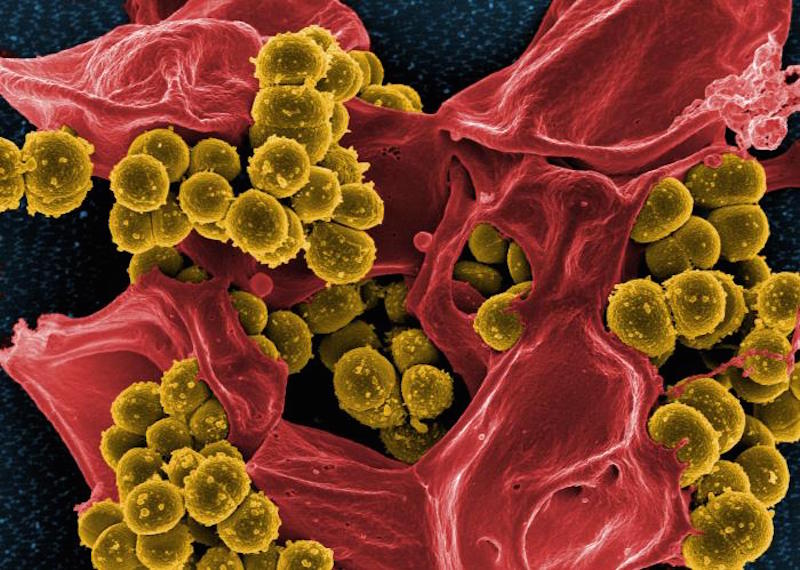

MRSA "superbug"

Short for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA is a type of "staph" bacterium that is capable of causing life-threatening skin and bloodstream infections and is resistant to most antibiotics used to treat such infections.

MRSA's resistance to antibiotics began in the 1940s, when doctors started treating staph infections with penicillin. The overuse (and misuse) of the drug helped microbes evolve resistance to penicillin within a decade, according to a feature in Harvard Magazine, causing doctors to start treating staph infections with the drug methicillin. But MRSA developed resistance to methicillin, as well. In fact, the superbug is now resistant to many penicillin-like antibiotics, including amoxicillin, oxacillin, dicloxacillin and all others in the beta-lactam class of antibiotics.

Staph infections on the skin typically start off as small red bumps but can turn into large abscesses that need to be surgically drained, according to the Mayo Clinic. More serious infections with the bacteria can occur throughout the body, including the blood, heart and bones. Such infections can be deadly.

Pertussis

Also known as whooping cough, pertussis is a bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis. As its name suggests, the telltale symptom of whooping cough is severe coughing.

Pertussis is particularly dangerous for babies, who can experience apnea, or pauses in breathing, as a result of the prolonged coughing fits brought about by the disease, according to the CDC. About 50 percent of infants who become sick with whooping cough need to be hospitalized, and 25 percent of those who are hospitalized develop lung infections, according to the CDC. Most people who died from whooping cough (87 percent) between 2000 and 2012 were babies less than 3 months old. The best way to prevent pertussis is to get vaccinated, according to the CDC. There are two vaccines for whooping cough, one for children younger than 7, called DTap, and one for older children, teens and adults, called Tdap.

Tetanus

The same vaccine that defends against pertussis (Tdap) can also protect you from tetanus, an infection caused by the bacteria Clostridium tetani. Once in the body, C. tetani produces a toxin that causes painful muscle contractions, according to the CDC. The neck and jaw are usually the first parts of the body affected by the disease, leading to tetanus' other name, "lockjaw."

The bacteria that cause tetanus enter through the skin but live in dirt or soil (as well as stuff lying around in the dirt, like rusty nails) and on the intestines of animals and people.

Meningitis

Meningitis refers to inflammation of the meninges, or the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. This infectious disease can be caused by a number of things, including fungi, viruses and bacteria. [Related: 5 Meningitis Facts You Need to Know]

Bacterial and viral meningitis are the most common types and can be spread from person to person. Whereas bacterial meningitis is often spread through kissing, viral meningitis is typically spread when someone comes into contact with the feces of an infected person (i.e. when changing a diaper or when a person doesn't wash his or her hands properly after using the toilet), according to the CDC.PLAY SOUND

Some people get meningitis after suffering a head injury, having brain surgery or having certain kinds of cancer. This type of meningitis is not contagious, nor is fungal meningitis, which was responsible for a meningitis outbreak in the U.S. in 2012.

Some people with meningitis develop meningococcal disease, which is caused by the bacteria Neisseria meningitides. The disease causes flu-like symptoms, as well as nausea, vomiting, increased sensitivity to light and an abnormal or confused mental state, according to the CDC.

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease that is easily treated but can lead to serious complications if neglected. In the first stage of the disease, sores may appear on a person's genitals or anus. Usually these sores are small and painless, and they heal on their own, leading many people to simply overlook them or confuse them with ingrown hairs or blemishes.

The second stage of the disease is more noticeable and usually begins with a rash on one or more parts of the body. Sometimes these rashes can be very faint, and since they don't itch, people infected with the disease might not know they have it. Others may develop more severe symptoms such as fever, swollen lymph glands and muscle aches.

If syphilis is left untreated throughout the first and second stages of the illness, it can cause much more severe problems later on, according to the CDC. Some people don't develop symptoms of the late stage of syphilis until 10 to 30 years after they contract the disease. Late-stage symptoms include difficulty coordinating muscle movements, paralysis, numbness, blindness and dementia. The disease can also damage internal organs, which may result in death.

SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, is the virus behind the 2002 and 2003 pandemic that killed more than 750 people worldwide. SARS is spread to people by bats, much like Ebola viruses, Marburg virus and MERS. The SARS virus likely originated in horseshoe bats in China, according to the National Institutes of Health.

SARS is characterized by high fever, dry cough, shortness of breath and pneumonia, according to the WHO.

Leprosy

A contagious, chronic disease, leprosy is caused by a bacterium known as Mycobacterium leprae. Also called Hansen's disease, after the Norwegian doctor who found the responsible bacterium, leprosy affects the skin, peripheral nerves, upper respiratory tract and eyes. If left untreated, it can cause muscle weakness, disfigurement and permanent nerve damage, according to the WHO. [Related: 6 Strange Facts About Leprosy]

People with leprosy used to be quarantined to prevent the spread of the disease, but as doctors now know, the condition is not highly contagious. The disease is transmitted through droplets expelled when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Simply touching a person with leprosy will usually not cause infection, and a healthy person's immune system can typically ward of infection with the bacteria that cause the disease, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine. However, children are at greater risk of contracting leprosy than adults.

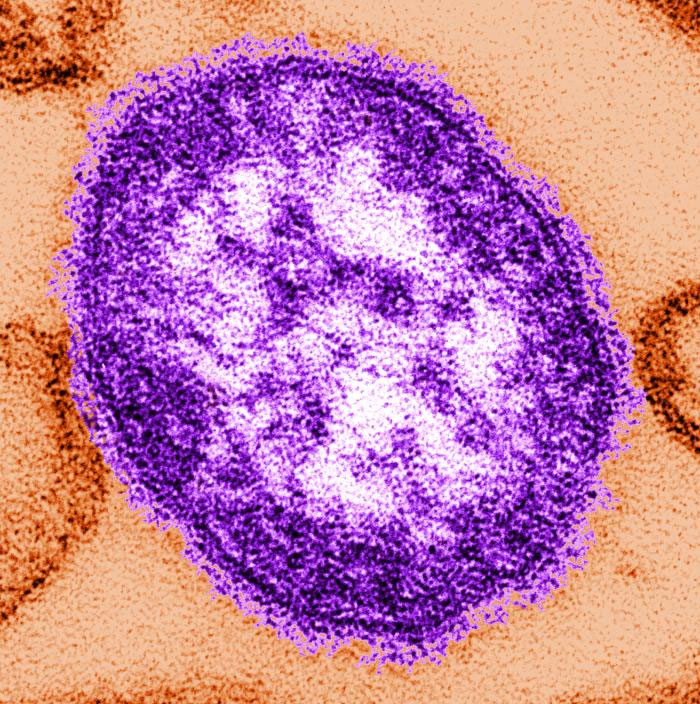

Measles

One of the most contagious of all infectious diseases, measles (also called rubeola) causes a characteristic red rash on the skin. Other symptoms of this viral disease are similar to that of the common cold.

Measles is so contagious that 90 percent of the people who simply stand near someone with the virus will become infected, according to the CDC.

"Near means within 50 feet or entering a room where the measles person had been in — even two hours after the infected person left the room," Aileen M. Marty, professor of infectious diseases at the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine and member of the WHO Advisory Group on Mass Gatherings, told Live Science.

Luckily, there's an easy way to defend yourself against the measles virus: Get vaccinated. Out of every 1,000 people vaccinated against measles, 997 will never get the disease.

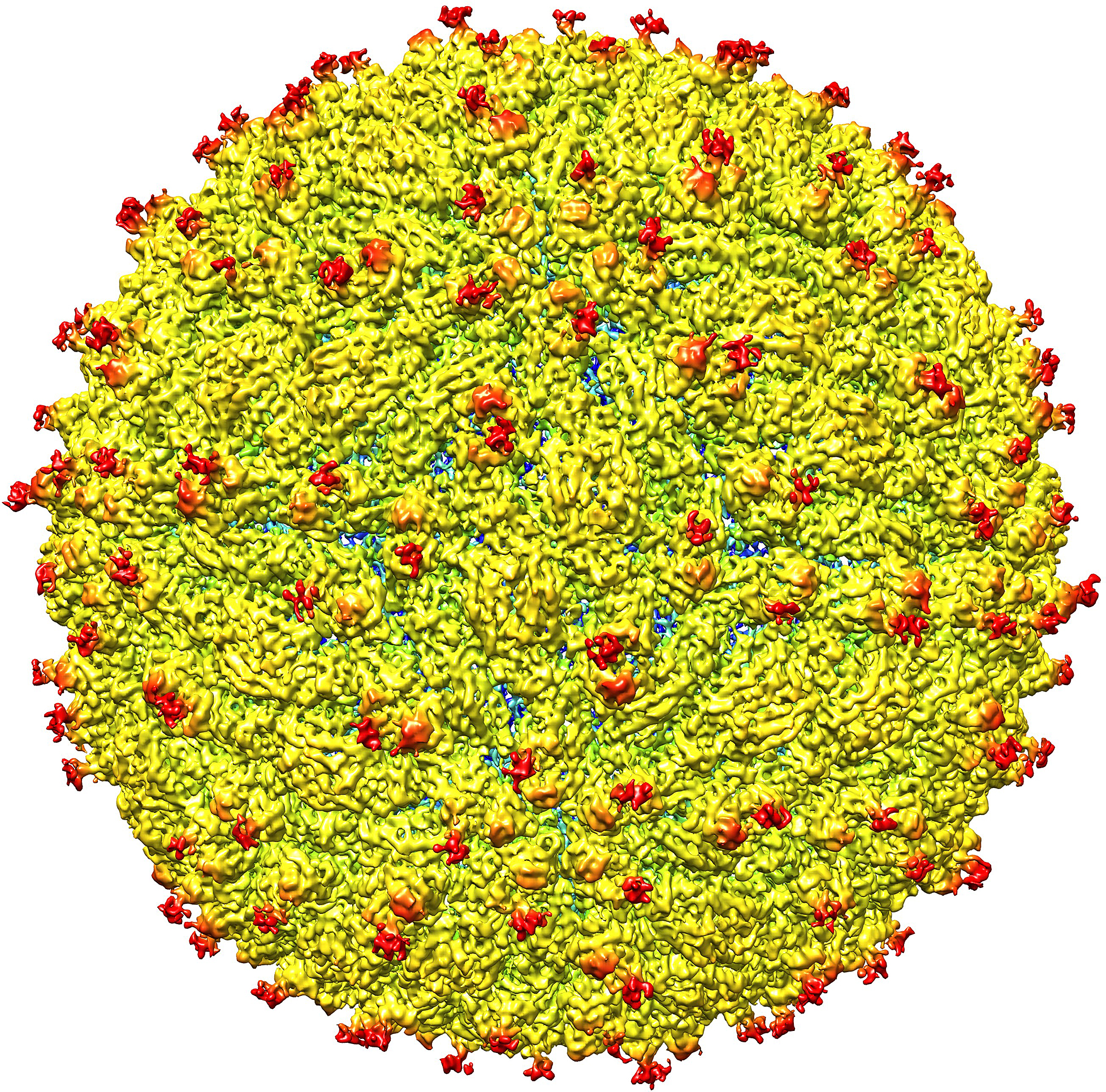

Zika

First identified in Africa in 1947, Zika virus is a flavivirus spread by mosquitoes in the Aedes genus. While the disease caused by Zika virus isn't particularly dangerous for most people, it can cause serious complications for fetuses and newborns.

Only one in five people infected with the virus becomes ill, according to the CDC. Those who do become ill may have a fever, rash, joint pain and conjunctivitis (pink eye), but these symptoms are typically mild and last only a few days. However, serious birth defects, particularly microcephaly, have been linked to the Zika virus, and the virus can also cause miscarriage in pregnant women, according to the Pan American Health Organization.

Originally published on Live Science.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents