Surprising Find: Sonic Booms May Shape Cosmic Strings

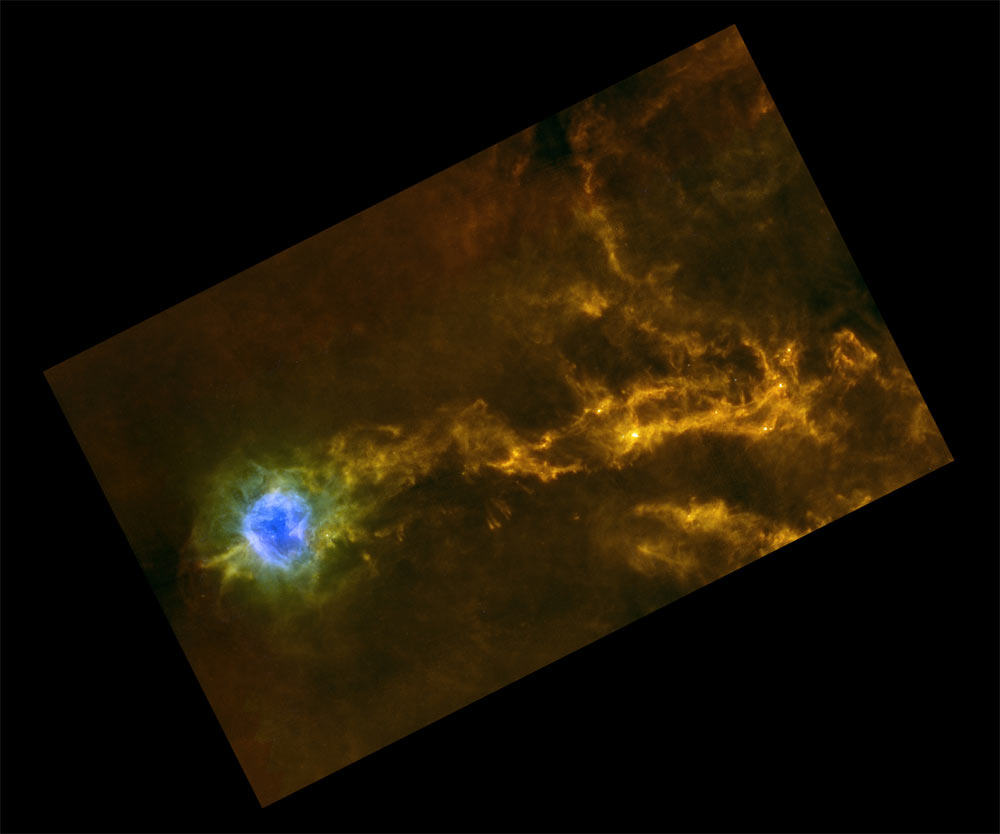

New images from space reveal a photogenic, yet puzzling, look at tangled cosmic filaments that may be shaped by interstellar sonic booms throughout our galaxy.

The filaments are strings of gas in nearby clouds between stars in our galaxy. Intriguingly, each filament is approximately the same width, giving scientists a clue of how they are formed, astronomers said.

The photos come from the European Space Agency's Herschel space observatory, which observes the cosmos through the largest infrared telescope ever to be flown in space.

The filaments are huge, stretching for tens of light-years across space, with stars often crowding together in the densest parts of the strings. One filament observed by Herschel in the Aquila region contains a cluster of about 100 infant stars.

A surprising find

While previous studies have observed filaments, no telescope has been able to measure their widths clearly enough. The new photos from Herschel allowed scientists to discover that, regardless of the length or density of a filament, the width is always about the same.

"This is a very big surprise," lead researcher Doris Arzoumanian, of the Laboratoire AIM Paris-Saclay, said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Arzoumanian and her colleagues analyzed 90 filaments and found they were all about 0.3 light-years across, or about 20,000 times the distance of Earth from the sun. This consistency of the widths demands an explanation, they said. [Strangest Things in Space]

Supersonic shockwaves

The astronomers compared the observations with computer models, and concluded that filaments are probably formed when slow shockwaves dissipate in the interstellar clouds.

These shockwaves are mildly supersonic and are a result of the copious amounts of turbulent energy injected into interstellar space by exploding stars. They travel through the dilute sea of gas found in the galaxy, compressing and sweeping it up into dense filaments as they go.

Interstellar clouds are usually extremely cold, about 10 degrees Kelvin above absolute zero, and this makes the speed of sound in them relatively slow, at just 447 mph (720 kph). For comparison, the speed of sound in Earth's atmosphere at sea-level is 760 mph (1,224 kph).

These slow shockwaves are the interstellar equivalent of sonic booms.

The scientists suggest that as the sonic booms travel through the clouds, they lose energy and, where they finally dissipate, they leave these filaments of compressed material.

"This is not direct proof, but it is strong evidence for a connection between interstellar turbulence and filaments," said co-researcher Philippe André, also of the Laboratoire AIM Paris-Saclay. "It provides a very strong constraint on theories of star formation."

The team made the connection by studying three nearby clouds, known as IC5146, Aquila, and Polaris, using Herschel’s SPIRE and PACS instruments.

"The connection between these filaments and star formation used to be unclear, but now thanks to Herschel, we can actually see stars forming like beads on strings in some of these filaments," said Göran Pilbratt, the ESA Herschel project scientist.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.