World's First Known Toothache Revealed in Ancient Reptile

An elderly reptile living approximately 275 million years ago in what is now Oklahoma was probably walking around with a throbbing mouth, suggests a new study finding evidence of what may be the world's first known toothache.

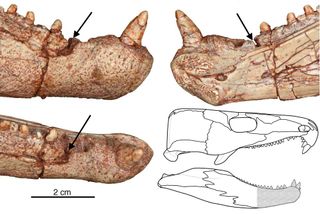

The find predates the previous record-holder (another land vertebrate with dental disease) by nearly 200 million years. The newly discovered tooth infection may have been the result of animals adapting to life on land after living in the sea for so long. [Image of decaying jawbone]

"Not only does this fossil extend our understanding of dental disease, it reveals the advantages and disadvantages that certain creatures faced as their teeth evolved to feed on both meat and plants," said lead researcher Robert Reisz, a biologist at the University of Toronto Mississauga. "In this case, as with humans, it may have increased their susceptibility to oral infections."

The finding may have implications for understanding this animal's death as well. "The question then arises, 'Did it die because of the infection?' We cannot tell. But it probably was a contributing factor," Reisz said. For instance, a toothache like that may have kept an animal from eating, and if you're an old individual like this reptile, you'd be more susceptible to weakening and then predation, Reisz said.

Toothy find

Reisz and his colleagues studied the jaws from several specimens of an ancient reptile called Labidosaurus hamatus from North America. They noticed one of the largest individuals in the sample had missing teeth and a damaged jawbone. Due to its size, the researchers think the individual was probably a senior citizen for his particular species.

Looking at the bone with CT scans, the team found evidence of a massive infection, which resulted in the missing teeth and an abscess and tissue loss in the jawbone.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It looks like the animal broke its tooth and because it doesn't replace its tooth, that became a hole — and through that hole, oral bacteria probably entered the inside of the jaw and then gradually the jaw was closed up," Reisz told LiveScience.

He added that it was likely a pretty bad infection. "The infection raveled about four or five teeth into the area where the jaw is quite thin, and that's where it went into the mouth area and the outside of the jaw," Reisz said. "As a consequence, that area of the jaw is really damaged." [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

New teeth

As the ancestors of reptiles adapted to life on land, many evolved features so they could feed more efficiently on terrestrial meals (other animals and plants high in fiber). That forced a change from the primitive dental setup — where teeth were loosely attached to the jaws and continuously replaced —to teeth that were strongly attached to the jaw, with little or no tooth replacement. The new strategy likely helped animals like Labidosauris to chew their food better, thus improving nutrient absorption.

The researchers argue the abundance and global distribution of Labidosauris and its kin suggest the toothy change was an evolutionary success.

Human susceptibility to oral infection has some parallels to those of ancient reptiles that evolved to eat a diet incorporating plants in addition to meat.

"Our findings suggest that our own human system of having just two sets of teeth, baby and permanent, although of obvious advantage because of its ability to chew and process many different types of food, is more susceptible to infection than that of our distant ancestors that had a continuous cycle of tooth replacement," Reisz said.

The study is detailed online in the journal Naturwissenschaften - The Science of Nature.

You can follow LiveScience managing editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.