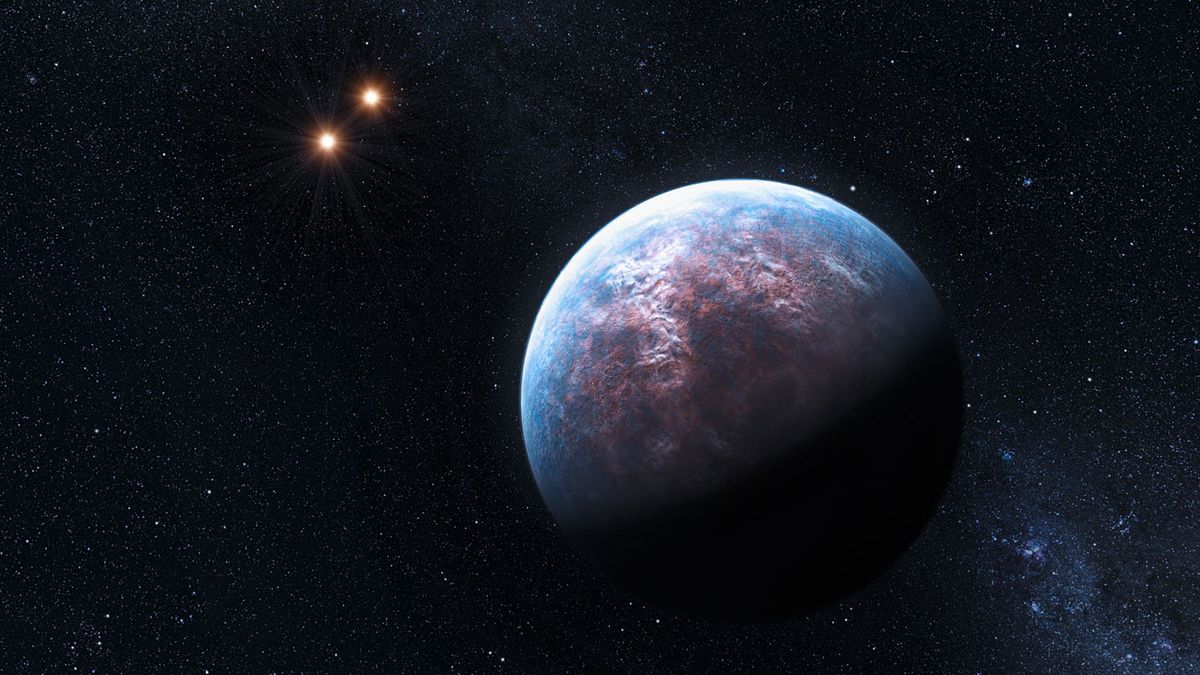

Planets With Two Suns Could Grow Black Trees

Luke Skywalker's home planet of Tatooine is a vivid desert world under two suns, but it may be missing one key detail: black trees.

According to a new study, Earth-like alien planets with multiple suns may host trees and shrubs that are black or gray instead of the more familiar green.

It all depends on the particulars of the light available for photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert sunlight into energy. Photosynthesis produces oxygen and ultimately provides the basis for most life on Earth. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

"If a planet were found in a system with two or more stars, there would potentially be multiple sources of energy available to drive photosynthesis," study lead author Jack O'Malley-James, of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, said in a statement. "The temperature of a star determines its color and, hence, the color of light used for photosynthesis. Depending on the colors of their starlight, plants would evolve very differently."

Green not a given

Most plants on Earth are green because they enlist a biomolecule called chlorophyll to drive photosynthesis. Chlorophyll absorbs sunlight in the blue and red wavelengths most strongly, which makes sense; blue light is extremely energetic, and our sun throws off red light in great volumes.

Chlorophyll reflects sunlight around the green part of the electromagnetic spectrum, on the other hand, which is why leaves look green to us.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But there's no guarantee that plants on alien worlds would do things the same way. Alien shrubs might be orange or red, for example, depending on what wavelengths of light are available to them. [A Field Guide to Alien Planets]

In the study, O'Malley-James and his colleagues assessed the potential for photosynthetic life in multi-star systems with different combinations of sunlike stars and red dwarfs. They chose these star types advisedly; sunlike stars are known to host exoplanets, and red dwarfs are the most common type of star in our galaxy.

Red dwarfs are also commonly found in multi-star systems, and many astronomers think they're old and stable enough to give life a chance to take root. More than 25 percent of sunlike stars and 50 percent of red dwarfs are found in multi-star systems, researchers said.

The team performed computer simulations in which Earth-like planets either orbit two stars close together or circle one of two widely separated stars. The team also looked at combinations of these scenarios, with two nearby stars and one more distant star.

They found that alien planets orbiting such stars mght indeed host plant life very different than the green stuff we're used to here on Earth. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

"Plants with dim red dwarf suns, for example, may appear black to our eyes, absorbing across the entire visible wavelength range in order to use as much of the available light as possible," O'Malley-James said.

O'Malley-James presented the team's results today (April 18) at the Royal Astronomical Society's national meeting in Llandudno, Wales.

Did George Lucas get it right?

Alien plants would adjust to their stars in other ways as well. If their host world orbited two brighter sunlike stars, for instance, they might evolve their own sunscreens to block harmful ultraviolet radiation, researchers said. Some plants on Earth can do this as well.

Or alien plants might harbor photosynthesizing microbes that can move in response to sudden solar flares, O'Malley-James said.

Of course, this is all speculation, because scientists have yet to find conclusive evidence of any life forms beyond Earth. And speaking of speculation — Tatooine's twin stars appear to be bright suns similar to our own, rather than cool red dwarfs. So any plants on the planet's scorching surface might not want to soak up as much radiation as possible — meaning they might not be black after all.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.