Did a Supernova Mark 17th Century King's Birth?

The royal wedding in England this month is sure to be packed full of pomp, but a 17th century king of Great Britain might have the event trumped with a supernova that announced his birth, researchers say. The theory places the star explosion's discovery 50 years earlier than previously thought.

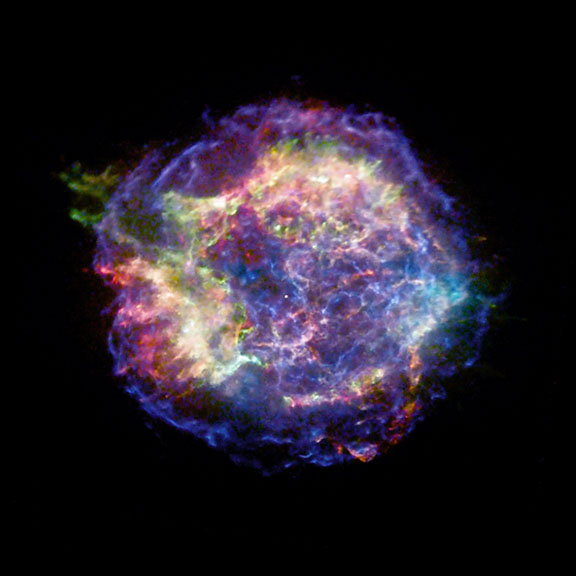

The glowing hot cloud known as Cassiopeia A is the remnant of a massive star explosion — a supernova — that occurred about 11,000 light-years away from Earth. The light from that cosmic detonation was first visible on Earth when it arrived sometime in the 17th century.

But the exact date of when Cas A's explosion could have been seen from Earth has been a longstanding mystery in astronomy. Records suggest the first "astronomer royal" of England, John Flamsteed, may have recorded the supernova in 1680.

Still, the light from the supernova should have been easily visible to everyone in the sky.

Now researchers argue that it was widely seen — as a "new" star that may have marked the birth of the future King Charles II of Great Britain on May 29, 1630. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

Merry monarch is born

Charles II, often known as the "Merry Monarch" for his lively, hedonistic court, allegedly had a "noon-day star" appear at his birth. This became a key (and perhaps dubious) feature in later propaganda of the restoration of the monarchy that brought him into power — his father, Charles I, was executed in 1649 at the climax of the English Civil War.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I saw a reproduced image of Charles II's 'noon-day star' in a book and had a eureka moment," said researcher Martin Lunn, former curator of astronomy at the Yorkshire Museum in England. "It fit the classic description of a supernova, and I wondered if it might be an observation of Cas A."

Lunn then sought to see how airtight the case was for dating Cas A to the latter half of the 17th century. [Video: Supernovas: Destroyers and Creators]

"The evidence for the light arriving sometime in the latter half of the 17th century is based on assumed distances to Cassiopeia A, as well as an assumed constant rate of speed for the knots of ejected gas — both of these assumptions, however, are problematic," Lunn told SPACE.com. "We can't be certain of the exact distance of Cas A, and the speed of the knots of gas could have varied due to interstellar material. These variables mean at best we've only been able to come up with an average range of dates. Considering this ambiguity, a 1630 date for Cas A isn't beyond the realm of possibility."

The trail continues

At the same time, historian Lila Rakoczy investigated what historical evidence there might have been for this noon-day star. There are many sources from the early 1660s cite this light in the sky over Charles II's birth, including the poet John Dryden.

"Going back a little further, William Lilly, the famous Parliamentarian astrologer, refers to the star, but dismisses it as Venus, in his 1651 book, 'Monarchy or No Monarchy,'" Rakoczy said. "I know of no references to the star in the 1640s, but this is not surprising considering the country was preoccupied with the English Civil War."

"Although plentiful, all of these sources are problematic because they appear 20 to 30 years after the alleged event, and the star event was used in the 1660s as a major tool of Restoration propaganda, which makes it harder to trust the accuracy of the event," Rakoczy explained.

"The strength of our case is that we have found a book, 'Britanniae Natalis,' from 1630, the year of Charles II's birth, which helps address both problems — it isn't too far removed in time from the event itself, and the English Civil War and Restoration haven't happened yet, which means the political undercurrents of the writing are far less problematic," she told SPACE.com. "Moreover, the book has over a hundred authors, all of whom were connected to Oxford University and consisted of the cream of Britain's intelligentsia of the day. Collectively, they represent a multitude of academic disciplines, political persuasions and social backgrounds. One of them is even John Bainbridge, the first Savilian professor of astronomy, so it's a pretty impressive collection of characters."

"The number and variety of sources that refer to the new star strongly suggest that an astronomical event really did take place," Lunn said. "Our work raises questions about the current method for dating supernovae, but leads to the exciting possibility of solving a decades-old astronomical puzzle."

"Our ideas have the potential to radically alter the way astronomers calculate the distance to Cassiopeia A, the speed the material is moving away from the center of the explosion, and how the material might react with the interstellar medium around it," he added. "It may also possibly open doors for the next generation of astronomers studying Cassiopeia A by allowing them to consider the problem from a different dimension."'

Lunn and Rakoczy will detail their findings April 18 at the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting in Llandudno, Wales.

A controversial claim?

The researchers do expect their work to attract controversy.

"The date of 1670 is almost universally used by astronomers — it has become somewhat stuck in a lot of people's minds," Lunn said. "By proposing this earlier date, our results challenge astronomers to completely review their investigations, which is something that many of them will be reluctant to do. The fact that this is a joint astronomy-history investigation rather than being a purely astronomy one will also make some wary of our conclusions. Arguably, we are operating outside the comfort zones of a lot of mainstream astronomers."

"My hope is that those working on Cas A will simply give our case a fair hearing before they make up their minds," Rakoczy said.

In terms of future work, "it would be interesting to see if other observations can be found in the documentary record around 1630 — not just in Britain but in other countries," Rakoczy said. "No one, to our knowledge, has actively gone looking for them."

"As to whether or not we'll see a noon-day star appearing on April 29, I couldn't possibly predict, although I somehow doubt it," Rakoczy quipped.

Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.