New Aussies: Ancient Snail-Chomping Marsupials Discovered

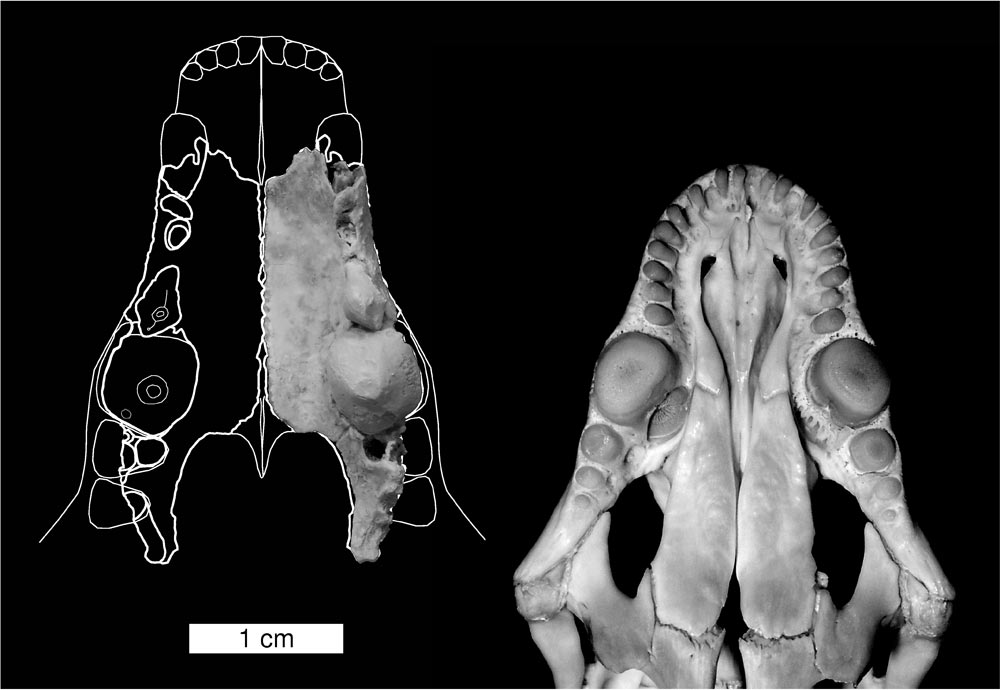

Strange hammerlike teeth seen in two newfound species of ancient marsupials -- teeth unknown in any other mammal -- were the weapons they once used to smash open snail shells.

Oddly, a bizarre group of lizards alive today in the rain forests of eastern Australia possess extraordinarily similar teeth, and their ancestors might have driven those snail-eating marsupials to extinction struggling over their sluggish prey. [Image of fossil marsupial]

The fossil marsupials, discovered in semi-arid northern Australia, are 10 million to 17 million years old, and lived back when the area was a temperate lowland forest. The ferret-sized species are named Malleodectes mirabilis and Malleodectes moenia -- Latin and Greek for "extraordinary hammer-biter" and "fortified hammer-biter," respectively.

These creatures each had enormous premolars, which in humans would be located between the canines and molars. The specimen they first investigated "appeared so odd that initially none of the team could work out exactly what it was," researcher Rick Arena, a paleontologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia, told LiveScience. "The teeth were unlike any we had ever seen before in a mammal, so we were scratching our heads."

The researchers think these unusual teeth might have been used like ball-peen hammers to crack open hard objects. Although no known mammals possess such teeth, remarkably similar dentition is seen in the pink-tongued skink, Cyclodomorphus gerrardii, a 16-inch (40-centimeter) lizard that lives in rain forests and wet forests on the Australian east coast, which uses its powerful teeth to crush snail shells.

The level of similarity between these unusual teeth is the most striking example seen yet between a mammal and a lizard, researchers said. The degree to which they match also suggests they likely vied against each other over snails if they lived in the same area.

"We are not sure exactly why the hammer-toothed, snail-eating marsupials became extinct," Arena said. "However, they seem to have died out some time after 10 million years ago, when the Australian continent began to respond to rapid climate change. During this time, once expansive regions of forest retracted toward the coast while more arid habitats expanded. It is possible these conditions began to favor lizards over mammals and the mammals lost out."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

@font-face { font-family: "Arial"; }@font-face { font-family: "Arial Unicode MS"; }p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Arial Unicode MS"; }a:link, span.MsoHyperlink { color: blue; text-decoration: underline; }a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed { color: purple; text-decoration: underline; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

These fossils come from Riversleigh in northern Australia, an area that has produced a huge number of fossils that span the last 25 million years, including the ancestors of the modern Australian creatures such as kangaroos, koalas, wombats and many others, as well as some previously unknown animals, such as this hammer-toothed snail-eating marsupial.

"The fossils improve our understanding of the origins and evolution of the Australian fauna, as well as documenting how ecosystems have been affected by changes in climate and the environment during the last 25 million years," Arena said. "Despite the vast numbers of fossils uncovered so far at Riversleigh, only a very small number of specimens of Malleodectes have ever been found. We will keep searching for more fossils of these fascinating creatures in order to find out more about them."

The scientists detailed their findings online April 20 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Crop circles surround Iraq's multicolored 'Sea of Salt' after years of drought — Earth from space

Watch humanlike robot with bionic muscles dangle as it twitches, shrugs and clenches its fists in creepy video

'The parasite was in the driver's seat': The zombie ants that die gruesome deaths fit for a horror movie