Surprise Finding: Why Japan's Earthquake Was So Strong

The first two hours of Japan's massive magnitude 9.0 earthquake has revealed surprising information about how such huge earthquakes rupture.

The earthquake ruptured several areas of a fault that in the past have ruptured alone, contrary to what many scientists would have predicted. If the earthquake had recruited still more nearby segments where massive aftershocks struck, the quake could have been even bigger, said Eric Kiser, a graduate student at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., who presented data on the first few hours of the rupture at the Seismological Society of America meeting held last week in Memphis, Tenn.

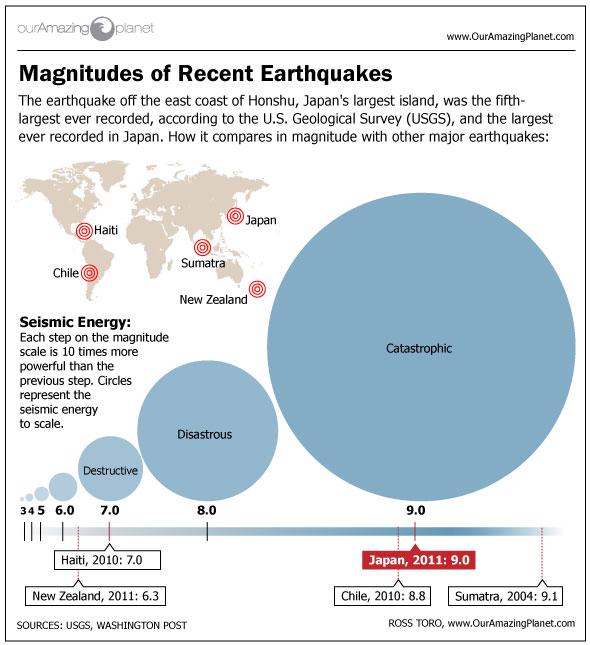

The March 11 earthquake is now the fourth largest ever recorded in the world. The quake struck off the coast of the Tohoku region of Japan, triggering a deadly tsunami that may have killed nearly 30,000 people. The rumbling didn't end with this massive rupture, and it hasn't stopped today. More than 60 aftershocks of magnitude 6.0 or greater have struck the region. [Related: Listen to Japan's Huge Earthquake]

The main rupture lasted more than 3.5 minutes, although most of the energy was released in the first 2 minutes, Kiser told OurAmazingPlanet. The rupture associated with the main shock was about 155 miles (250 kilometers) long and 109 miles (175 km) wide, Kiser said.

Then came the aftershocks.

Over the first few hours after the initial temblor, several aftershocks hit, many with a magnitude of 6.4 or greater. The largest aftershock to date was a magnitude 7.9 that struck less than an hour after the main shock.

All told, the quake ruptured five areas within the region that have previously ruptured as separate earthquakes, according to preliminary data. The fact that these areas linked together during the March 11 quake is probably why it was unexpectedly large, Kiser said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The way the quake ruptured is contrary to the previously held idea of segmentation — that the fault is segmented into areas that are more likely to rupture individually, said Morgan Page, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who has been studying the Japan quake.

"That's why the Japanese seismic hazard maps did not assume that an earthquake this large could hit this region — because in previous cases that area did not all rupture together in one big quake," Page told OurAmazingPlanet.

- Japan's Tsunami: How It Happened

- Photos: Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in Pictures

- Japan's Biggest Earthquakes

Email OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Brett Israel at bisrael@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @btisrael.