Kicking Up Cosmic Dust: Asteroid Brightening Caused By Collision

The strange metamorphosis astronomers observed in an asteroid late last year was likely caused by a collision with another space rock, according to two new studies.

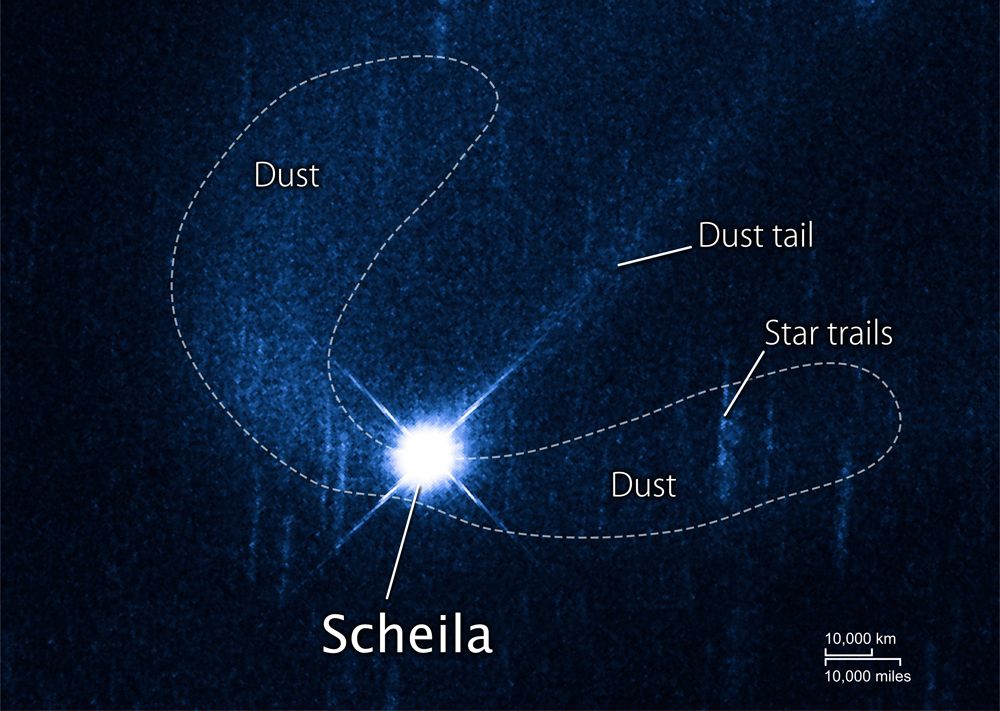

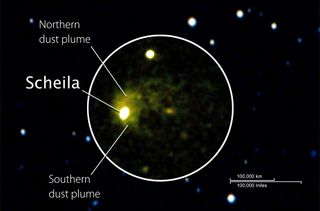

In December 2010, astronomers noticed that an asteroid named (596) Scheila had brightened unexpectedly. Not only that, the space rock was sporting some new and short-lived dust plumes. These changes were probably brought on by a smashup with a smaller asteroid, according to the studies, which were based on observations made by NASA's Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes.

"Collisions between asteroids create rock fragments, from fine dust to huge boulders, that impact planets and their moons," said Dennis Bodewits of the University of Maryland, lead author of the Spitzer study. "Yet this is the first time we've been able to catch one just weeks after the smashup, long before the evidence fades away."

Keeping an eye on Scheila

Asteroids are rocky fragments thought to be debris from the formation and evolution of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. Millions of them orbit the sun between Mars and Jupiter in the main asteroid belt. [Photos of Asteroids in Deep Space]

Scheila is approximately 70 miles (113 kilometers) wide and orbits the sun every five years. Its most recent lap, apparently, has not gone smoothly.

On Dec. 11, 2010, images from the University of Arizona's Catalina Sky Survey revealed Scheila to be twice as bright as expected, and immersed in a faint cometlike glow. Looking through the survey's archived images, astronomers determined that Scheila's outburst began between Nov. 11 and Dec. 3.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers soon trained the eyes of Spitzer and Hubble on Scheila to see what was going on. A collision with another asteroid, after all, wasn't the only possibility.

Researchers recently learned that some objects categorized as asteroids aren't always inert hunks of rock. Rather, they're "dormant comets" that can come back to life in some parts of their orbit and start shedding water vapor.

Some researchers initially thought this might be the case with Scheila. But in mid-December, Swift captured multiple images and a spectrum of the asteroid, which showed that the fuzz around Scheila was dust and not gas. So, Scheila wasn't just going through a cometlike outgassing phase.

Hubble observations from late December and early January confirmed and further refined this view.

"The Hubble data are most simply explained by the impact, at 11,000 mph (17,703 kph), of a previously unknown asteroid about 100 feet (30 meters) in diameter," said Hubble team leader David Jewitt at the University of California in Los Angeles. [Video: Crashing Boulders to Mimic Asteroid Collisions]

Scheila's dual dust plumes -- a bright one in the north and a fainter one in the south -- were formed when small particles ejected by the crash were pushed away from the asteroid by sunlight, researchers said. Hubble did not see any discrete collision fragments, unlike its 2009 observations of P/2010 A2, the first identified asteroid collision.

The studies will appear in the May 20 edition of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A massive dust cloud

The two teams worked out some likely details of the crash. A small asteroid likely smashed into Scheila at an angle of less than 30 degrees, leaving a crater 1,000 feet (305 m) across. Lab experiments showed that a more direct strike probably wouldn't have produced two distinct dust plumes, researchers said.

The scientists estimate the crash ejected more than 660,000 tons of dust -- equivalent to nearly twice the mass of the Empire State Building in New York City.

"The dust cloud around Scheila could be 10,000 times as massive as the one ejected from comet 9P/Tempel 1 during NASA's UMD-led Deep Impact mission," said Michael Kelley, also of the University of Maryland. "Collisions allow us to peek inside comets and asteroids. Ejecta kicked up by Deep Impact contained lots of ice, and the absence of ice in Scheila's interior shows that it's entirely unlike comets."

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.