Moon Microbe Mystery Finally Solved

There has been a long-lived bit of Apollo moon landing folklore that now appears to be a dead-end affair: microbes on the moon.

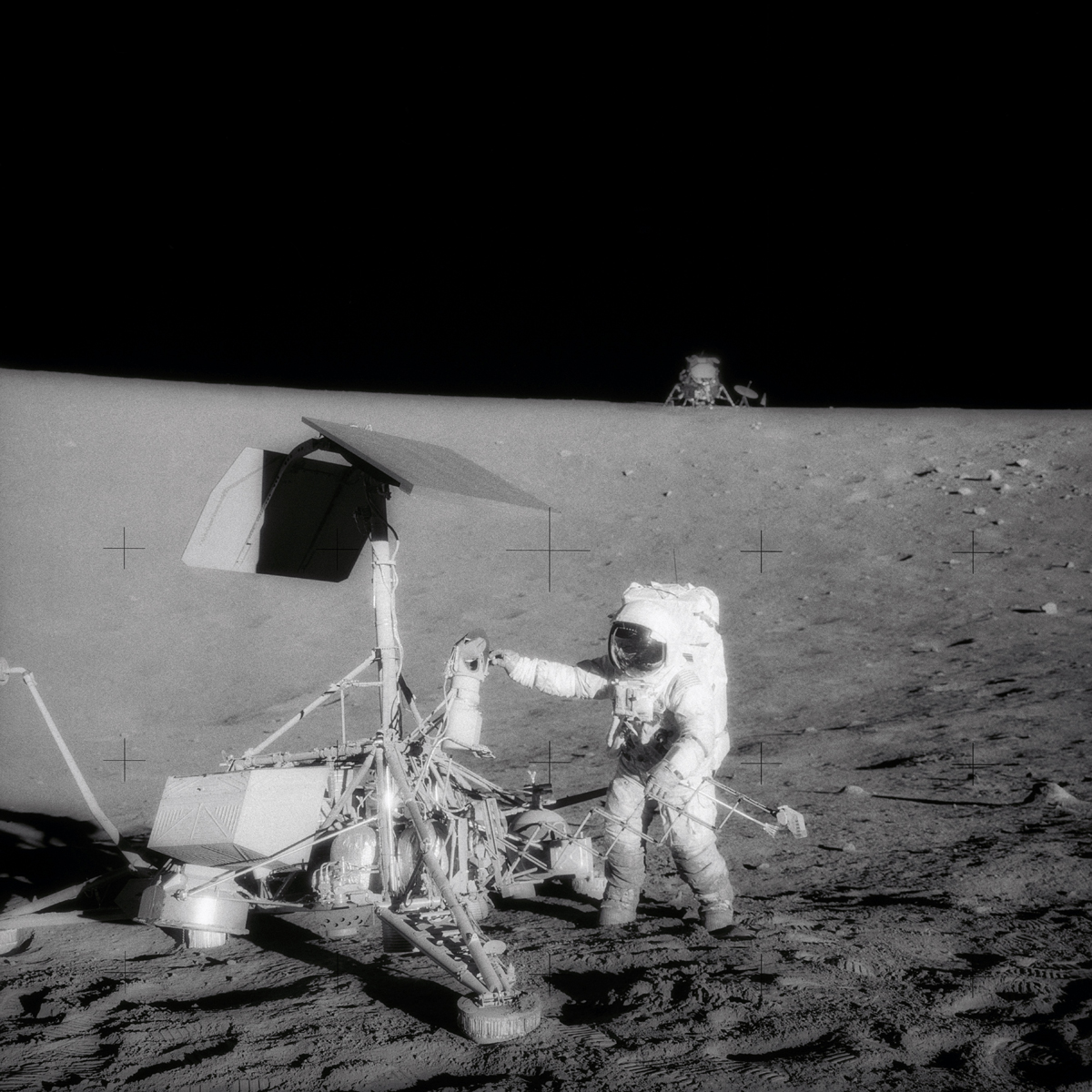

The lunar mystery swirls around the Apollo 12 moon landing and the return to Earth by moonwalkers of a camera that was part of an early NASA robotic lander – the Surveyor 3 probe.

On Nov. 19, 1969, Apollo 12 astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean made a precision landing on the lunar surface in Oceanus Procellarum, Latin for the Ocean of Storms. Their touchdown point was a mere 535 feet (163 meters) from the Surveyor 3 lander -- and an easy stroll to the hardware that had soft-landed on the lunar terrain years before, on April 20, 1967. [Video: Apollo 12 Visits Surveyor 3 Probe]

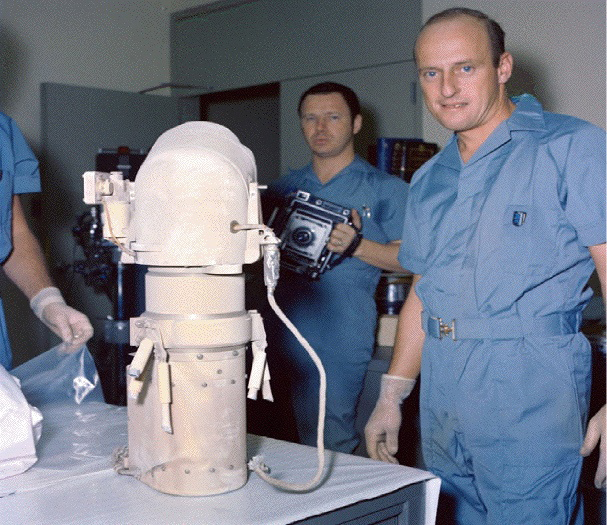

The Surveyor 3 camera was easy pickings and brought back to Earth under sterile conditions by the Apollo 12 crew. When scientists analyzed the parts in a clean room, they found evidence of microorganisms inside the camera.

In short, a small colony of common bacteria -- Streptococcus Mitis -- had stowed away on the device.

The astrobiological upshot as deduced from the unplanned experiment was that 50 to 100 of the microbes appeared to have survived launch, the harsh vacuum of space, three years of exposure to the moon's radiation environment, the lunar deep-freeze at an average temperature of minus 253 degrees Celsius, not to mention no access to nutrients, water or an energy source. [Photos: Our Changing Moon]

Now, fast forward to today.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

NASA's dirty little secret?

A diligent team of researchers is now digging back into historical documents -- and even located and reviewed NASA's archived Apollo-era 16 millimeter film -- to come clean on the story.

As it turns out, there's a dirty little secret that has come to light about clean room etiquette at the time the Surveyor 3 camera was scrutinized.

"The claim that a microbe survived 2.5 years on the moon was flimsy, at best, even by the standards of the time," said John Rummel, chairman of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) Panel on Planetary Protection. "The claim never passed peer review, yet has persisted in the press -- and on the Internet -- ever since." [Coolest New Moon Discoveries]

The Surveyor 3 camera-team thought they had detected a microbe that had lived on the moon for all those years, "but they only detected their own contamination," Rummel told SPACE.com.

A former NASA planetary protection officer, Rummel is now with the Institute for Coastal Science & Policy at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C.

Rummel, along with colleaguesJudith Allton of NASA’s Johnson Space Center and Don Morrison, a former space agency lunar receiving laboratory scientist, recently presented their co-authored paper: "A Microbe on the Moon? Surveyor III and Lessons Learned for Future Sample Return Missions."

Poor space probe hygiene

Their verdict was given at a meeting on "The Importance of Solar System Sample Return Missions to the Future of Planetary Science," in March at The Woodlands,Texas, sponsored by the NASA Planetary Science Division and Lunar and Planetary Institute.

"If 'American Idol' judged microbiology, those guys would have been out in an early round," the research team writes of the way the Surveyor 3 camera team studied the equipment here on Earth. Or put more delicately, "The general scene does not lend a lot of confidence in the proposition that contamination did not occur," co-author Morrison said.

For example, participants studying the camera were found to be wearing short-sleeve scrubs, thus arms were exposed. Also, the scrub shirt tails were higher than the flow bench level … and would act as a bellows for particulates from inside the shirt, reports co-author Allton.

Other contamination control issues were flagged by the researchers.

In simple microbiology 101 speak, "a close personal relationship with the subject ... is not necessarily a good thing," the research team explains.

All in all, the likelihood that contamination occurred during sampling of the Surveyor 3 camera was shown to be very real.

A cautionary tale

On one hand, Rummel emphasized that today’s methods for handling return samples are much more effective at detecting microbes.

However, the Surveyor 3 incident back then raises a cautionary flag for the future.

"We need to be orders of magnitude more careful about contamination control than was the Surveyor 3 camera-team. If we aren't, samples from Mars could be drowned in Earth life upon return, and in all of that 'noise' we might never have the ability to detect Mars life we may have brought back, too," Rummel said. "We can, and we must, do a better job with a Mars sample return mission."

Winner of this year's National Space Club Press Award, Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines and has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years.