6 Weird Facts About Gravity

Gravity: You don't know what you've got 'til it's gone

Here on Earth, we take gravity so for granted that it took an apple falling from a tree to trigger Isaac Newton's theory of gravitation. But gravity, which draws objects together in proportion to their mass, is about much more than fallen fruit. Read on for some of the strangest facts about this universal force.

It's all in your head

Gravity may be pretty consistent on Earth, but our perception of it isn't. According to research published in April 2011 in the journal PLoS ONE, people are better at judging how objects fall when they're sitting upright versus lying on their sides.

The finding means that our perception of gravity may be less based on visual cues of gravity's real direction and more rooted in the orientation of the body. The findings may lead to new strategies to help astronauts deal with microgravity in space.

Coming down to Earth is tough

Speaking of astronauts, their experience has shown that a switch to weightlessness and back can be tough on the body. In the absence of gravity, muscles atrophy and bones likewise lose bone mass. According to NASA, astronauts can lose 1 percent of their bone mass per month in space.

When astronauts come back to Earth, their bodies and minds need time to recover. Blood pressure, which has equalized throughout the body in space, has to return to an Earthly pattern in which the heart must work hard to keep the brain nourished with blood. Occasionally, astronauts struggle with that adjustment. In 2006, astronaut Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper collapsed at a welcome-home ceremony the day after returning from a Space Shuttle mission to the International Space Station.

The mental readjustment can be just as tricky. In 1973, Skylab 2 astronaut Jack Lousma told Time magazine that he'd accidentally smashed a bottle of aftershave in his first days back from a month-long sojourn in space. He'd let go of the bottle in mid-air, forgetting that it would crash to the ground rather than just float there.

For weight loss, try Pluto

Pluto may no longer be a planet, but it's still a good bet for lightening up. A 150-pound (68 kilogram) person would weigh no more than 10 pounds (4.5 kg) on the dwarf planet. The planet with the most crushing gravity, on the other hand, is Jupiter, where the same person would weigh more than 354 pounds (160.5 kg).

The planet humans are most likely to visit, Mars, would also leave explorers feeling light-footed. Mars' gravitational pull is only 38 percent that of Earth's, meaning a 150-pound person would feel like they weigh about 57 pounds (26 kg).

Gravity is lumpy

Even on Earth, gravity isn't entirely even. Because the globe isn't a perfect sphere, its mass is distributed unevenly. And uneven mass means slightly uneven gravity.

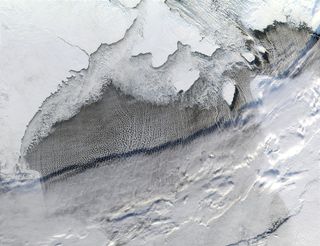

One mysterious gravitational anomaly is in the Hudson Bay of Canada (shown above). This area has lower gravity than other regions, and a 2007 study finds that now-melted glaciers are to blame.

The ice that once cloaked the area during the last ice age has long since melted, but the Earth hasn't entirely snapped back from the burden. Since gravity over an area is proportional to the mass atop that region, and the glacier's imprint pushed aside some of the Earth's mass, gravity is a bit less strong in the ice sheet's imprint. The slight deformation of the crust explains 25 percent to 45 percent of the unusually low gravity; the rest may be explained by a downward drag caused the motion of magma in Earth's mantle (the layer just beneath the crust), researchers reported in the journal Science.

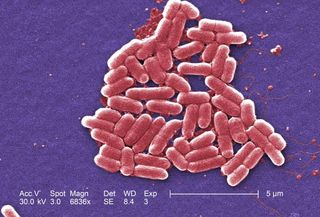

Without gravity, some bugs get tougher

Bad news for space cadets: Some bacteria become nastier in space. A 2007 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that salmonella, the bacteria that commonly causes food poisoning, becomes three times more virulent in microgravity. Something about the lack of gravity changed the activity of at least 167 salmonella genes and 73 of its proteins. Mice fed the gravity-free salmonella got sick faster after consuming less of the bacteria.

In other words, Michael Crichton's "The Andromeda Strain" had it wrong: The danger of infection in space may not come from space bugs. It's more likely our own bugs grown stronger would strike us.

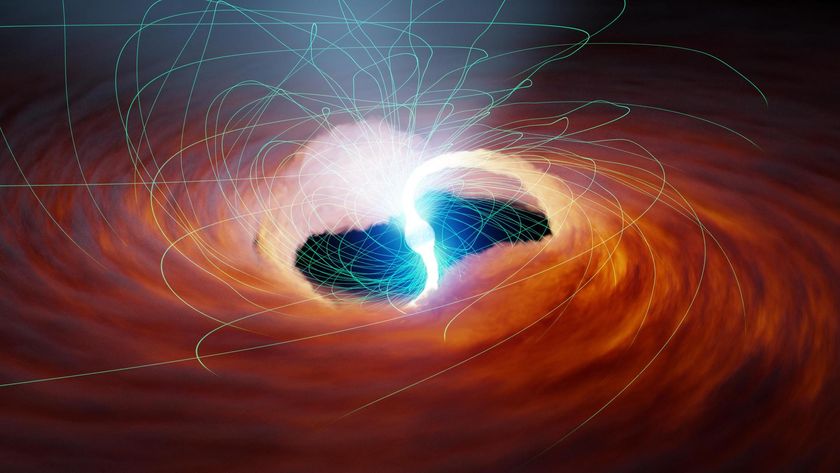

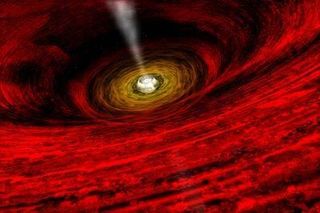

Black holes at the center of galaxies

Named because nothing, not even light, can escape their gravitational clutches, black holes are some of the most destructive objects in the universe. At the center of our galaxy is a massive black hole with the mass of 3 million suns. Scarier thought? It might be "just resting," according Kyoto University scientist Tatsuya Inui.

The black hole isn't really a danger to us Earthlings -- it's both far away and it's remarkably calm. But sometimes it does put on a show: Inui and colleagues reported in 2008 that the black hole sent out a flare of energy 300 years ago. Another study, released in 2007, found that several thousand years ago, a galactic hiccup sent a small amount of matter the size of Mercury falling into the black hole, leading to another outburst.

The black hole, named Sagittarius A*, is dim compared with other black holes.

"This faintness implies that stars and gas rarely get close enough to the black hole to be in any danger," Frederick Baganoff, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was involved with the 2007 study, told LiveScience's sister site SPACE.com. "The huge appetite is there, but it's not being satisfied."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.