NASA Gravity Probe Confirms Two Einstein Theories

A NASA probe orbiting Earth has confirmed two key predictions of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, which describes how gravity causes masses to warp space-time around them.

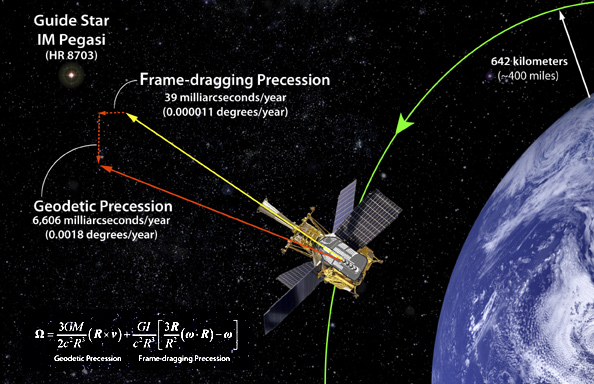

The Gravity Probe B (GP-B) mission was launched in 2004 to study two aspects of Einstein's theory about gravity: the geodetic effect, or the warping of space and time around a gravitational body, and frame-dragging, which describes the amount of space and time a spinning objects pulls with it as it rotates.

"Imagine the Earth as if it were immersed in honey," Francis Everitt, GP-B principal investigator at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif., said in a statement. "As the planet rotates, the honey around it would swirl, and it's the same with space and time. GP-B confirmed two of the most profound predictions of Einstein's universe, having far-reaching implications across astrophysics research." [6 Weird Facts About Gravity]

Gravity Probe B used four ultra-precise gyroscopes to measure the two gravitational hypotheses. The probe confirmed both effects with unprecedented precision by pointing its instruments at a single star called IM Pegasi.

If gravity did not affect space and time, GP-B's gyroscopes would always point in the same direction while the probe was in polar orbit around Earth. However, the gyroscopes experienced small but measurable changes in the direction of their spin while Earth's gravity pulled at them, thereby confirming Einstein's theories. [Video: Flying Space-time's Warps and Twists]

"The mission results will have a long-term impact on the work of theoretical physicists," said Bill Danchi, senior astrophysicist and program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. "Every future challenge to Einstein's theories of general relativity will have to seek more precise measurements than the remarkable work GP-B accomplished." [Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

A long time coming

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These results conclude one of the longest-running projects in NASA history. The space agency became involved in the development of a relativity gyroscope experiment in 1963.

Decades of research and testing led to groundbreaking technologies to control environmental disturbances that could affect the spacecraft, such as aerodynamic drag, magnetic fields and thermal variations. Furthermore, the mission's star tracker and gyroscopes were the most precise ever designed and produced.

The GP-B project has led to advancements in GPS technologies that help guide airplanes to landings. Additional innovations were applied to NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer mission, which accurately determined the universe's background radiation left over from shortly after the Big Bang.

The drag-free satellite concept pioneered by GP-B made a number of Earth-observing satellites possible, including NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment. These satellites provide the most precise measurements of the shape of the Earth, which are critical for navigation on land and sea, and understanding the relationship between ocean circulation and climate patterns.

Gravity Probe B's wide reach

The GP-B mission also acted as a training ground for students across the United States, from candidates for doctorates and master's degrees to undergraduates and high school students. In fact, one undergraduate who worked on GP-B went on to become the first female astronaut in space, Sally Ride.

"GP-B adds to the knowledge base on relativity in important ways and its positive impact will be felt in the careers of students whose educations were enriched by the project," said Ed Weiler, associate administrator for the science mission directorate at NASA headquarters.

GP-B completed its data collection operations and was decommissioned in December 2010. The probe's findings were published online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.