Saturn's Moon Titan May Have Been Planetary Punching Bag

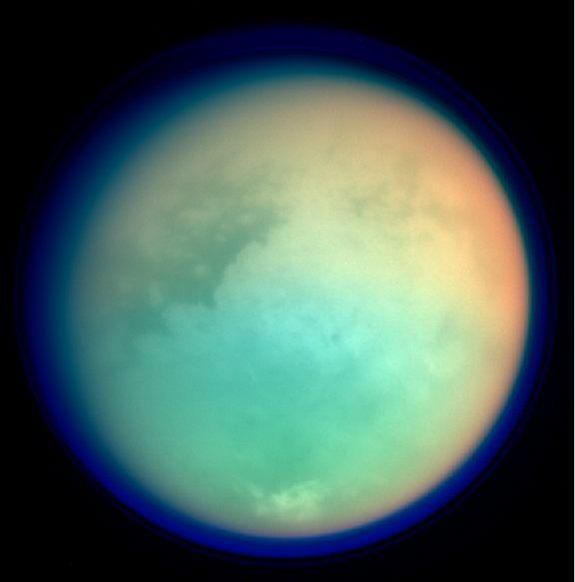

An untold number of cosmic impacts could have created the mysteriously thick atmosphere of Saturn's largest moon Titan, suggest experiments with laser guns.

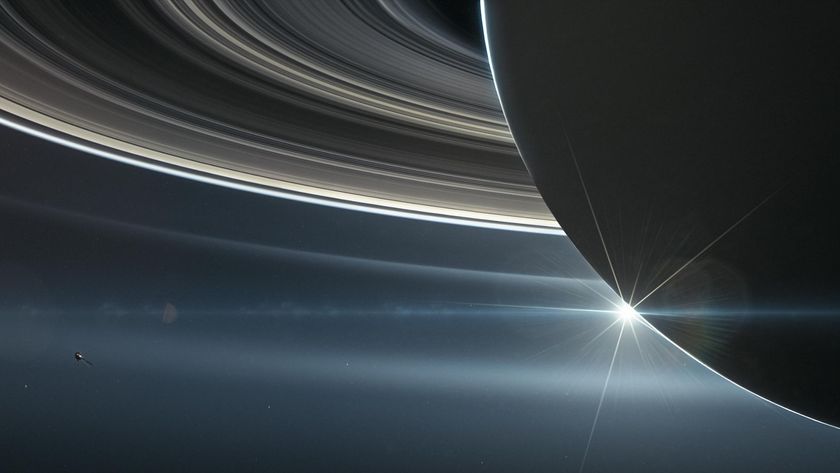

Titan has always stood out as the only moon in the solar system with a substantial atmosphere. In fact, the surface pressure on Titan is 50 percent greater than the pressure on Earth. [Photos: The Rings and Moons of Saturn]

The main ingredient of Titan's atmosphere is nitrogen, just as it is on Earth. Where this nitrogen came from has long been debated. For instance, it could be primordial, accumulating as Titan formed, or it could have originated later.

Weighing the options

In 2005, the Huygens probe carried by NASA's Cassini spacecraft to Saturn ruled out a primordial origin for this nitrogen. Titan's atmosphere apparently has extremely low levels of the isotope argon-36, while high amounts are expected in an atmosphere rich in primordial nitrogen.

There are a number of other explanations for how this atmospheric nitrogen might have formed after Titan's birth. For instance, sunlight in Titan's atmosphere might have broken apart ammonia, a molecule made of nitrogen and hydrogen.

However, nearly all these suggestions require that Titan formed at relatively high temperatures, which would have led the moon to differentiate into a rocky core and an icy mantle layer, and Cassini's radar scans suggested that Titan is not fully differentiated. Comets loaded with nitrogen might have delivered it to Titan, but that would have also led to higher levels of argon-36 than currently seen.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

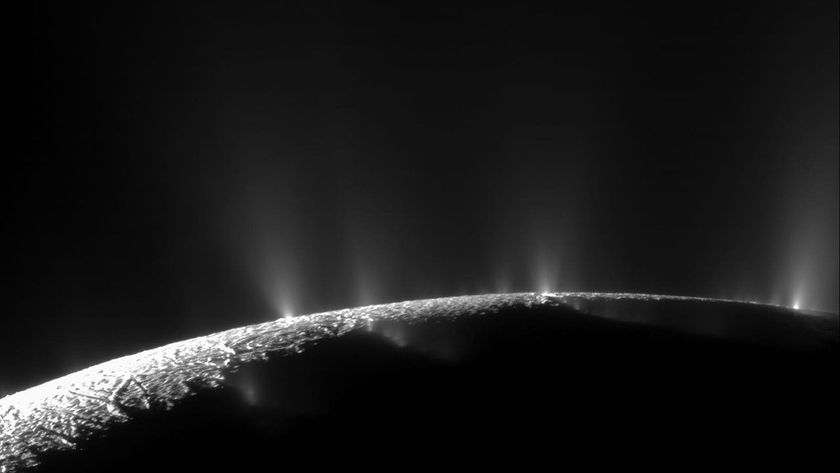

Now scientists in Japan suggest that countless numbers of asteroids and comets slamming into ammonia ice on Titan could have converted it to nitrogen gas several hundred million years after the moon's formation.

"Our results suggest that hypervelocity impacts have played a key role," researcher Yasuhito Sekine, a planetary scientist at the University of Tokyo, told SPACE.com.

Solar system dodgeball

During an era known as the Late Heavy Bombardment about four billion years ago, the solar system was very much like a shooting gallery, with cosmic impacts regularly blasting planets and moons. To see if such impacts would deliver enough energy to convert ammonia ice to nitrogen, researchers used laser guns and "bullets" made of gold, platinum or copper foil. The beams vaporized the back of these bullets, propelling them at high speeds at targets made of ammonia and water ice.

The researchers found "ammonia is very easily converted to nitrogen molecule by impacts," Sekine said.

They calculated that 330 million billion tons (300 million billion metric tons) worth of impactors could have produced the current amount of nitrogen seen on Titan, "a plausible mass of impactors during the Late Heavy Bombardment," noted planetary scientist Catherine Neish at Johns Hopkins University, who did not take part in this research.

"It's an interesting new hypothesis," Neish told SPACE.com. "Differentiating between the different hypotheses will require a more detailed understanding of Titan's internal structure, and the composition of comets and-or other Saturnian satellites." She suggested that a future mission to a comet would very likely provide key evidence to help confirm or refute the idea.

One question would be where all the craters from such impacts might be. Titan has only about 50 recognized craters, Neish said. "Does this imply that Titan's surface is very young?" she asked, suggesting a young surface could have covered up most of the craters on Titan.

The scientists detailed their findings online May 8 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.