Alien Solar Systems Are Much Different Than Our Own

Alien solar systems with multiple planets appear to be common in our galaxy, but most of them are quite different than our own, a new study finds.

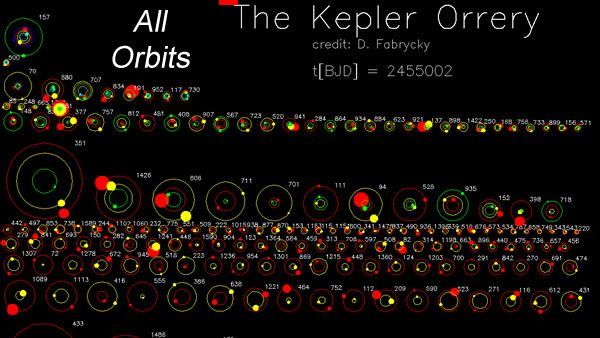

NASA's Kepler Space Telescope detected 1,235 alien planet candidates in its first four months of operation. Of those, 408 reside in multiple-planet systems, suggesting that our own configuration of multiple worlds orbiting a single star isn't so special.

What may be special, however, is the orientation of our solar system's planets. Some of them are tilted significantly off the solar system's plane, while most of the Kepler systems are nearly as flat as a tabletop, researchers said. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

Watching for transiting planets

The Kepler spacecraft launched in March 2009, tasked with searching for Earth-size alien planets in their stars' habitable zones — that just-right range of distances that can support liquid water.

Kepler finds these distant worlds by searching for tiny, telltale dips in a star's brightness that occur when a planet transits — or crosses in front of — it from Earth's perspective. The 1,235 candidate planets detected so far still need to be confirmed by follow-up studies, though researchers estimate at least 80 percent of them will pan out.

Nearly one-third of the Kepler candidates are part of multiple-planet solar systems, which came as a surprise to researchers. [Infographic: Stacking Up Alien Solar Systems]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We didn't anticipate that we would find so many multiple-transit systems," said astronomer David Latham, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in a statement. "We thought we might see two or three. Instead, we found more than 100."

Latham presented the findings today (May 23) at the 218th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Boston.

Strangely flat orbits

In our solar system, some planet orbits are tilted by up to 7 degrees, meaning that an alien astronomer looking for transits wouldn’t be able to detect all eight planets. In particular, they would miss Mercury and Venus, researchers said.

The planetary systems spotted by Kepler have orbits tilted less than 1 degree, they added.

These multiplanet systems are probably so flat because they lack Jupiter-size giant planets, whose gravitational influence can disrupt planetary systems, tilting the orbits of neighboring worlds, researchers said. [Video: Mapping Alien Worlds: How-To Guide]

"Jupiters are the 800-pound gorillas stirring things up during the early history of these systems," Latham said. "Other studies have found plenty of systems with big planets, but they’re not flat."

Finding multiple-planet systems is exciting for reasons beyond their superficial similarity to our own cosmic neighborhood. They could help astronomers confirm the densities of small, rocky, Earthlike alien worlds, which can be tough to pin down using the tried-and-true radial velocity method (which measures the wobble a large planet's gravity induces in its parent star).

In systems with more than one transiting planet, astronomers can use a technique called transit timing variations. They can measure how the time between successive transits changes from orbit to orbit due to gravitational interactions between planets. The size of the effect depends on the planets' masses.

"These planets are pulling and pushing on each other, and we can measure that," said Harvard-Smithsonian astronomer Matthew Holman. "Dozens of the systems Kepler found show signs of transit timing variations."

As Kepler continues to gather data, it will be able to spot planets with wider orbits, including some in the habitable zones of their stars. Transit timing variations may play a key role in confirming the first rocky planets in their stars' habitable zones, researchers said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.