Ancient Sea Monsters Were No Shrimps

Bizarre shrimp-like monsters that were the world's largest predators for millions of years grew even larger and survived much longer than thought, scientists find.

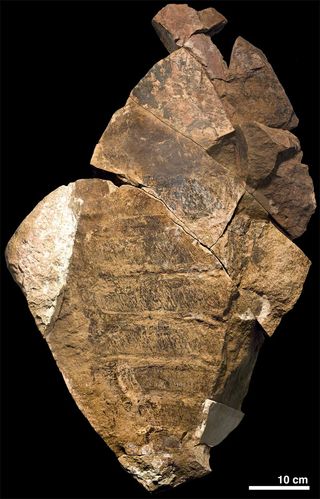

The creatures, known as anomalocaridids, were giant predators (ranging from 2 to possibly 6 feet in length) with soft-jointed bodies and toothy maws with spiny limbs in front to snag worms and other prey. [Image of the ancient sea monster]

"They were really at the top of the food chain," said researcher Peter Van Roy, a paleobiologist at Ghent University in Belgium, and formerly at Yale. "The uncontested top predators of their time."

Past research showed they dominated the seas during the early and middle Cambrian period 542 million to 501 million years ago, a span of time known for the "Cambrian Explosion" that saw the appearance of all the major animal groups and the establishment of complex ecosystems.

"The anomalocaridids are one of the most iconic groups of Cambrian animals," said researcher Derek Briggs, director of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. "These giant invertebrate predators and scavengers have come to symbolize the unfamiliar morphologies displayed by organisms that branched off early from lineages leading to modern marine animals and then went extinct.

Bigger and better

Fossils suggested these ancient marine predators grew to about 2 feet (0.6 meters) long. Prior studies also suggested they died out at the end of the Cambrian.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now, extraordinarily well-preserved fossils unearthed in the rocky desert in southeastern Morocco by local collector Mohammed Ben Moula reveal giant anomalocaridids that measured more than 3 feet (1 m) in length.

"The Moroccan specimens are the largest anomalocaridids known to date — they are about double the size of their Cambrian counterparts," Van Roy told LiveScience. "There have been suggestions of Cambrian anomalocaridids of over 6 feet (2 meters) in length, but these estimates are extrapolations from very fragmentary material, and hence not too reliable."

Moreover, these newly examined creatures date back to the period that followed the Cambrian, the early Ordovician, 488 million to 472 million years ago, meaning these predators lived for 30 million years longer than previously known.

"Now we know that they died out much more recently than we thought," Briggs said.

Beastly details

The fossils of the creatures revealed a series of more than 100 flexible blade-like structures in each segment across their backs. The researchers believe these filaments might have served as gills.

The animals lived on the muddy seafloor at least 330 feet (100 meters) below the surface. "The seafloor near which the animals lived would have been teeming with bottom life," Van Roy said. There would have been forests of fan-shaped colonies of creatures known as graptolites nearby, dense populations of various sponges, and lots of different creatures scurrying about them, such as starfish, mollusks and crustacean-like animals. [In Photos: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

These discoveries are just part of a new collection of fossils that includes thousands of specimens of soft-bodied marine animals. Soft tissues fossilize much less readily than hard bones and shells, leading to incomplete and biased views of the marine life that existed during the Ordovician period before the recent find in Morocco. The animals in this cache of fossils lived in fairly deep water, and were trapped by sediment clouds that buried and preserved them.

Many of the animals appeared oversized. "The large size of the Moroccan animals may be due to abundant food supplies," Van Roy said. "Also, at the time, the area where the animals lived was almost right at the South Pole, and organisms in high polar latitudes often tend to grow to larger sizes — this is something that can also be witnessed in current-day faunas."

Successful predators

These findings call into question the classical idea that animals of the Cambrian were quickly replaced during the Ordovician by more advanced creatures, the so-called Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event.

"The Cambrian faunas persisted for much longer, and replacement was a much more gradual and protracted affair, than the incomplete shell-biased fossil record would suggest," Van Roy said. "The fact that anomalocaridids persisted for so long shows that they remained well-adapted and highly successful predators long after the Middle Cambrian."

The reasons why anomalocaridids disappeared are not entirely clear yet. However, the Ordovician witnessed the rise of two other large predators, equal to or surpassing anomalocaridids in size — eurypterids, or sea scorpions, and nautiloids, which resembled squid with conical shells.

"It seems likely that anomalocaridids were outcompeted by these more advanced and better adapted predators," Van Roy said. "While anomalocaridids in essence are soft-bodied, eurypterids had a strong exoskeleton, and nautiloids had a sturdy shell and a powerful beak. It seems likely that, when anomalocaridids had to compete over food with these more advanced animals, they would likely lose out."

The scientists detailed their findings in the May 26 issue of the journal Nature.

Most Popular