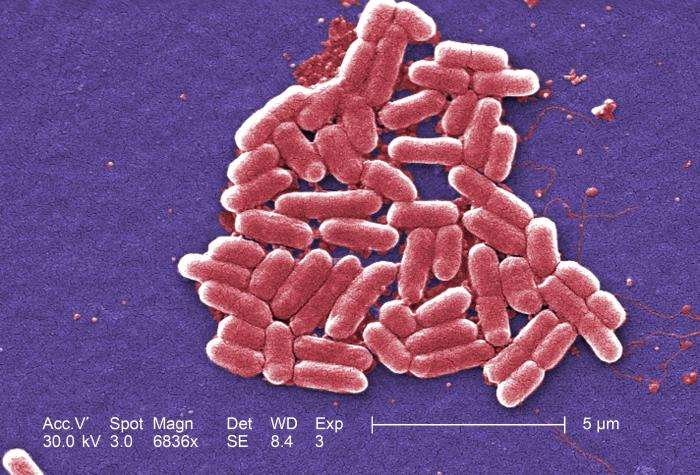

Can Copper Reduce E. Coli Outbreaks?

While the source of the deadly E. coli outbreak in Germany remains uncertain, the use of surfaces made of copper to handle food could reduce the risk of such outbreaks in the future, researchers say.

Furnishing workstations in meat processing factories with copper surfaces rather than stainless steel ones could reduce bacteria on these surfaces, researchers say.

A copper surface can rapidly kill bacteria and viruses upon contact. While copper surfaces can't completely stem outbreaks such as the current one, they could be an extra weapon against food-borne illness.

"There is no substitute for good hygiene," and hand washing and surface cleaning will still be necessary, said Bill Keevil, a microbiologist at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

"What we're saying is, adding a copper alloy surface is an extra defense barrier…an extra arrow in the quiver to control these pathogens," said Keevil , whose work is funded by the copper industry.

In a 2006 study, Keevil and his colleagues placed 10 million cells of E. coli O157, an infamous food-borne bacteria strain, on a copper surface. All the bacteria died in about an hour. More recently, the researchers found a copper surface can kill other strains of E. coli bacteria in about 10 minutes.

While the researchers did not test the strain of E. coli responsible for the Germany outbreak, Keevil predicted that copper would kill that strain as well.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Copper kills germs

Copper is a proven antimicrobial material. In 2008, the Environmental Protection Agency said copper alloy products containing more than 60 percent copper could claim to be antimicrobial.

Copper is already being used in hospitals — on door handles, bed rails and light switches — to combat the spread of infections. Recent studies have shown installing copper surfaces in hospital wards leads to a 90 percent reduction in the number of microorganisms on surfaces, Keevil said.

Is it toxic?

The metal kills bacteria in part by releasing ions that destroy DNA and punch holes in the bacteria cell membrane, Keevil said.

But while it's toxic to microorganisms, it poses little health threat to people, Keevil said. Copper is an essential nutrient for people, and if we take in too much, the body has mechanisms of getting rid of it, he said.

You should still avoid taking in too much of any metal, said Christopher Rensing, an associate professor in the department of soil, water, and environmental science at the University of Arizona. But while people who work with copper might want to be careful about over-exposure, as a surface material, it's unlikely to be toxic to humans, Rensing said.

Studies have also shown raw meat takes up very little copper, Keevil said.

Other researchers are looking to combat contamination by dipping food directly into solutions containing copper. Salam Ibrahim, a research professor of food sciences at North Carolina A & T State University, and his colleagues conducted a study last year that found very low concentrations of copper can be combined with lactic acid to kill E. coli O157 on the surface of lettuces and tomatoes. Low concentrations are favorable because at higher concentrations, it might affect the taste of the food, Ibrahim said. Without the lactic acid, low concentrations of copper had little effect on the bacteria, he said. Ibrahim and colleagues hope to make their solution into a product available for commercial use in the food industry.

Pass it on: Copper is an antimicrobial material. If used on food surfaces or the food itself, it may reduce the risk of outbreaks of food-borne illness.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.