Archaeology's Tech Revolution Since Indiana Jones

Let′s face it, Indiana Jones was a pretty lousy archaeologist. He destroyed his sites, used a bullwhip instead of a trowel and was more likely to kill his peers than co-author a paper with them. Regardless, "Raiders of the Lost Ark," which celebrates its 30th anniversary on June 12, did make studying the past cool for an entire generation of scientists. Those modern archaeologists whom "Raiders" inspired luckily learned from the mistakes of Dr. Jones, and use advanced technology such as satellite imaging, airborne laser mapping, robots and full-body medical scanners instead of a scientifically useless whip.

Such innovations have allowed archaeologists to spot buried pyramids from space, create 3-D maps of ancient Mayan ruins from the air, explore the sunken wrecks of Roman ships and find evidence of heart disease in 3,000-year-old mummies. Most of the new toolkit comes from fields such as biology, chemistry, physics or engineering, as well as commercial gadgets that include GPS, laptops and smartphones.

"If we dig part of a site, we destroy it," said David Hurst Thomas, a curator in anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. "Technology lets us find out a lot more about it before we go in, like surgeons who use CT and MRI scans."

Archaeologists have harnessed such tools to find ancient sites of interest more easily than ever before. They can dig with greater confidence and less collateral damage, apply the latest lab techniques to ancient human artifacts or remains, and better pinpoint when people or objects existed in time.

Satellites mark the spot

One of the current revolutions in archaeology relies upon satellites floating in orbit above the Earth. Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, and an international team recently used infrared satellite imaging to peer as far down as 33 feet (10 meters) below the Egyptian desert. They found 17 undiscovered pyramids and more than 1,000 tombs.

The images also revealed buried city streets and houses at the ancient Egyptian city of Tanis, a well-known archaeological site that was featured in "Raiders of the Lost Ark" three decades ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Obviously, we're not zooming in with satellite imaging to find the Ark of the Covenant and the Well of Lost Souls," Parcak said.

[Read More: 10 Modern Tools for Indiana Jones]

Even ordinary satellite images used by Google Earth have helped. Many of the old Egyptian sites have buried mud brick architecture that crumbles over time and mixes with the sand or silt above them. When it rains, soils with mud brick hold moisture longer and appear discolored in satellite photos.

"In the old days, I'd jump into the Land Rover and go look at a possible site," said Tony Pollard, director of the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. "Now, before that, I go to Google Earth."

Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has led a satellite imaging study to find buried pyramids, tombs and settlements in Egypt. Credit: University of Alabama at Birmingham

Digging with less damage

Tools such as ground-penetrating radar can also help archaeologists avoid destroying precious data when they excavate ancient sites, Thomas said.

"Many Native American tribes are very interested in remote sensing that is noninvasive and nondestructive, because many don't like the idea of disturbing the dead or buried remains," Thomas explained.

Magnetometers can distinguish between buried metals, rocks and other materials based on differences in the Earth's magnetic field. Soil resistivity surveys detect objects based on changes in electrical current speed.

Dusting off old bones

Once objects or bones have surfaced, archaeologists can return them to the lab for forensic analysis that would impress any CSI agent. Computed tomography (CT) scanners commonly used in medicine have revealed blocked arteries in an ancient Egyptian princess who ended up mummified 3,500 years ago.

Looking at the ratios of different forms of elements, called isotopes, in the bones of ancient people may reveal what they ate. The dietary details can include whether they favored foods such as corn or potatoes, or if they were strictly hunters.

A similar chemical signature based on the isotope ratio of different geographical locations can reveal where humans originally grew up. Archaeologists used it to identify the origins of dozens of soldiers found in a 375-year-old mass grave in Germany.

"Once they excavated them, they did analysis on bones and identified in most cases where individual soldiers came from," Pollard said. "Some came from Finland, some came from Scotland."

Back to the future

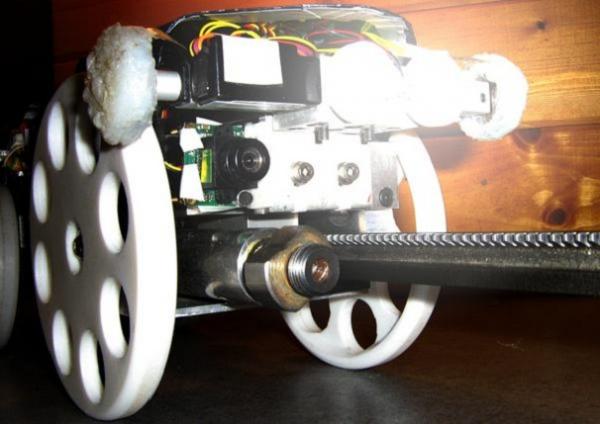

Archaeologists have many other new tools in the toolkit. The laser mapping technique used on the Mayan ruins, called LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging), has become a norm for archaeology in just a few years. Robots have begun exploring pyramids and caves as well as underwater shipwrecks.

"When I was a bad boy and went into archaeology instead of med school, my mother thought I'd spent all my time in the past," Thomas said. "It couldn't be further from the truth; we do all we can to keep up technologically."

Technology won't eliminate the need to dig anytime soon, archaeologists say. But if that day comes, "archaeology will get a lot more boring," Pollard said. He wasn't alone with that sentiment.

"It's all very well to use satellite imaging, but until you get out into the field, you're stuck in your lab," Parcak said. "It's a constant in archaeology; you've got to dig and explore."

You can follow InnovationNewsDaily senior writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.