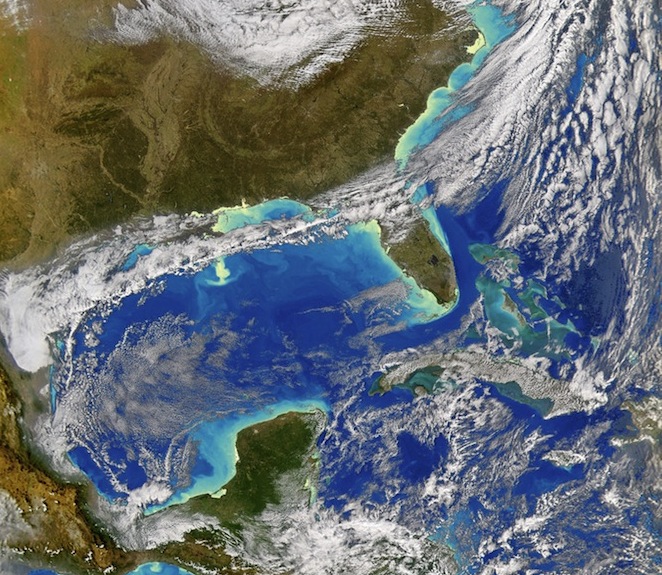

Mississippi Floods May Cause Record-Breaking Dead Zone in Gulf

The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is likely to be larger than average this year — possibly rivaling the state of New Hampshire in size — due to this spring's massive Mississippi River floods.

Scientists at Louisiana State University, the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and the University of Michigan predict that the low-oxygen dead zone could measure between 8,500 and 9,421 square miles. The largest Gulf dead zone on record was in 2002, encompassing more than 8,400 square miles.

Dead zones happen when excessive nutrients (usually nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer and other farming run-off) cause marine algae blooms. These blooms and their subsequent die-offs deplete the oxygen in the water column, leading to hypoxic, or low-oxygen, zones where life can't thrive.

Every summer, a hypoxic zone forms off the coast of Louisiana and Texas, threatening the commercial and recreational fisheries on the Gulf Coast. This year, the United States Geological Survey estimates, 164,000 metric tons of nitrogen were transported into the Gulf by the swollen Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers. In May alone, the nitrogen flow was 35 percent higher than the average rate measured in May in the last 35 years. That adds up to more nutrients in the Gulf and a greater likelihood of a giant dead zone. [Top 5 Mightiest Floods of the Mississippi River]

There is some uncertainty regarding how large this year's dead zone will grow, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) administrator Jane Lubchenco said in a statement. Nonetheless, she said, "the forecast models are in overall agreement that hypoxia will be larger than we have typically seen in recent years."

The spring floods may also lead to a surge in the giant invasive fish called the Asian carp in new areas of the Mississippi and Missouri river basins, scientists are now warning.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.