A NASA spacecraft circling Mercury is returning spectacular photos of the planet — and delivering some tantalizing surprises about the tiny, scorched world.

On March 17, NASA's Messenger probe became the first spacecraft ever to orbit Mercury. Since then, Messenger has already snapped more than 20,000 pictures and made observations that could help unlock long-standing mysteries of the solar system's innermost planet, researchers announced at a press conference today (June 16).

"We had many ideas about Mercury that were incomplete, ill-formed," said Messenger principal investigator Sean Solomon of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. "Many of those ideas are now having to be cast aside as we see orbital data for the first time." [Latest Messenger Photos of Mercury]

Mercury has 'personality'

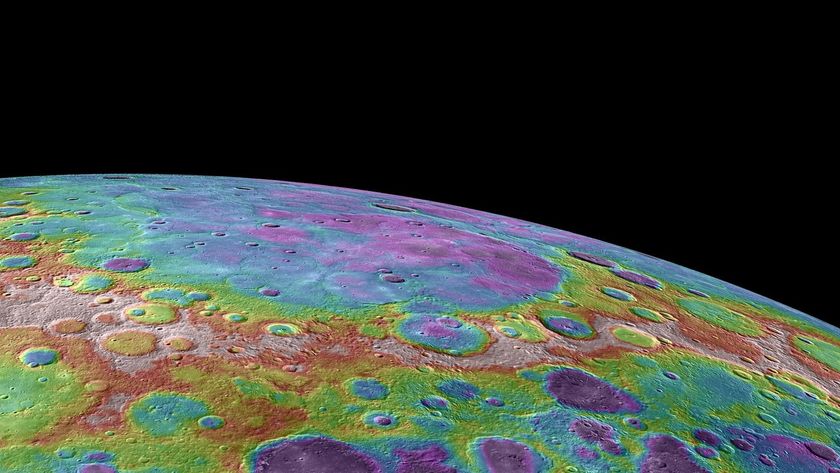

Messenger is photographing every inch of Mercury's surface from orbit, and some of its early pictures have revealed huge expanses of volcanic deposits near the planet's north pole. These features were detected by Messenger and NASA's Mariner 10 probe on previous Mercury flybys, but the new observations map them out in greater detail. [Infographic: The Messenger Mission]

"Now we're seeing their full extent for the first time," said Messenger scientist Brett Denevi of Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). And that extent is impressive; the northern volcanic plains cover 1.54 million square miles (4 million square kilometers) — nearly half the size of the continental United States.

These new observations help confirm that volcanism has substantially shaped Mercury's crust and surface for much of its history, researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Messenger has been scrutinizing Mercury with more than just its camera gear. The probe's X-ray spectrometer, for example, has already discovered that the planet's surface is made of different stuff than the moon, which is dominated by feldspar-rich rock.

The spectrometer has also detected surprisingly high levels of sulfur at the planet's surface, which could help scientists understand the nature of Mercury's origin and volcanism, researchers said.

So far, the spacecraft's observations are putting the lie to the notion that Mercury is similar to the moon. In fact, the early returns indicate that it's also very different than the other terrestrial planets, in ways that are only just beginning to come clear.

"Mercury really is a world in and of its own," said Messenger project scientist Ralph McNutt of APL. "Just like the Earth, it's got its own personality."

Water ice on Mercury?

Messenger is using another one of its seven instruments, a laser altimeter, to map out Mercury's topography. The spacecraft has already taken more than 2 million laser-ranging readings, revealing the planet's geological features in great detail.

"We're seeing the broad shape of the planet for the first time," Solomon said.

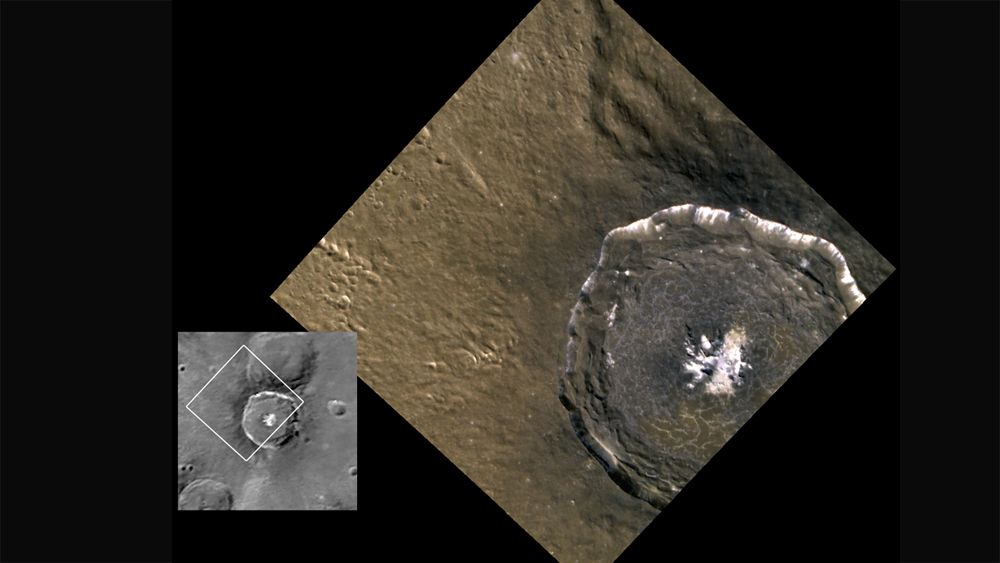

One of the many questions Messenger hopes to answer is whether or not Mercury harbors water ice on its surface. That might not seem very likely, since average surface temperatures on the planet can top 842 degrees Fahrenheit (450 degrees Celsius). However, Earth-based radar observations from 20 years ago suggest large amounts of ice may lurk in permanently shadowed craters at its poles.

And the early results from Messenger, which is mapping those craters with its altimeter, support this idea. Thus far, the probe's data indicate that some polar craters may be so deep that their floors are in permanent shadow. Whether they actually contain ice will have to be confirmed by different instruments, researchers said.

"Stay tuned," Solomon said. "The very first scientific test of that hypothesis using Messenger data from orbit has passed with flying colors."

Magnetic fields and more

Messenger has also been investigating the nature of Mercury's global magnetic field, which is of interest partly because Mercury is the only rocky planet in the solar system to possess one, other than Earth.

Mercury's magnetic field was thought to be more or less a miniature version of Earth's, researchers said. But Messenger's readings are showing that's not the case.

For starters, Mercury's magnetic field is asymmetrical, with its magnetic equator lying significantly north of the planet's geographic equator. This surprising geometry suggests that Mercury's south polar region is much more exposed than the north to bombardment by charged particles from the sun.

Scientists don't fully understand the import of many of Messenger's early findings. The probe is just 25 percent of the way through its planned one-year science mission around Mercury, after all.

"There's a lot more to come," McNutt said. "All I can say is to keep following us — the best is yet to be."

A long trip to Mercury

The $446 million Messenger mission — whose name is short for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging — launched in August 2004. It is designed to map Mercury fully for the first time and help answer several key questions about the planet. [The Greatest Mysteries of Mercury]

Mission scientists hope to learn, for example, why Mercury is so much denser than the other rocky planets. And they want to gain insights into how the planet's core is structured, the nature of its global magnetic field and other aspects of Mercury's composition and history.

Scientists hope all of this information will lead to an increased understanding of how our solar system — and solar systems in general — formed and evolved, researchers have said.

The spacecraft is now in an extremely oblong, or elliptical, orbit that brings it within 124 miles (200 kilometers) of Mercury at the closest point and retreats to more than 9,300 miles (15,000 km) away at the farthest point. Its orbital science mission is designed to last for 12 months.

While Messenger is the first mission ever to orbit Mercury, it is not the first spacecraft to visit the planet. NASA's Mariner 10 spacecraft flew by the planet three times in the mid-1970s. Messenger itself also made three flybys of the planet on its long, circuitous space journey, snapping photos all the while.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.