Icy Saturn Moon May Be Covering a Salty Sea

Saturn's icy moon Enceladus conceals a salty ocean beneath its frozen surface, scientists now suspect.

Using NASA's Cassini spacecraft orbiting Saturn, scientists have discovered that the water geysers erupting from Enceladus contain a significant amount of salt — enough to suggest the presence of a subterranean sea.

The finding might have implications for the possibility of life on Enceladus, researchers said.

A team of scientists led by Frank Postberg of the University of Heidelberg used Cassini's Cosmic Dust Analyzer to directly examine the plumes during three flybys by the Cassini spacecraft. Individual particles were analyzed as they hit a metal target, and the ones closer to the moon's surface were found to have a high salt content. [Photos: The Rings and Moons of Saturn]

"The salt-rich ice grains are, on average, heavier than the salt-poor ice grains," Postberg told SPACE.com in an email. "Only a relatively small fraction of the salty particles escape into the E ring." The E ring is the outermost of Saturn's seven ring groupings, and it is made up of particles ejected by Enceladus' geyser plumes.

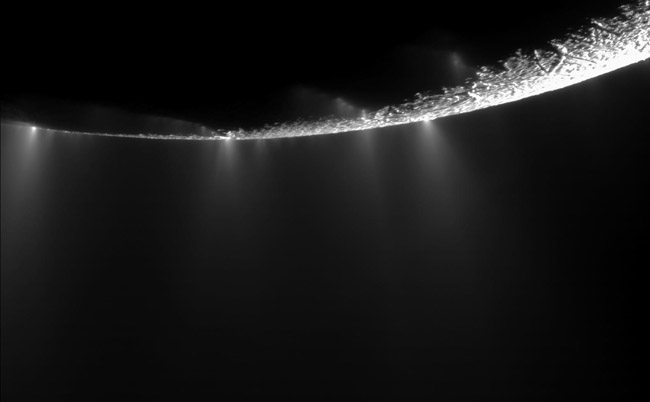

Geysers from Saturn moon

The idea of a salty sea beneath the icy crust of Saturn's sixth largest moon has been entertained since sodium was first detected in the planet's E ring. [Video:Enceladus: Saturn's Refreshing Secret]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But only about 6 percent of the ring particles were salty, suggesting that they were formed by ice that immediately evaporated into water vapor without forming a liquid, a process known as sublimation, researchers said.

Cassini discovered plumes of water vapor shooting from the southern hemisphere of Enceladus in 2005. The geysers erupt from four parallel trenches known as the "tiger stripes."

While previous studies found a relatively low amount of salt in the Enceladus geyser particles that make up Saturn's outer ring, the percentage is different when studying the geysers themselves.

"The lower you get to the surface, the more salt-rich grains you see," Postberg said.

In fact, more than 99 percent of the ice around the geysers is salt-rich.

"This makes a much stronger case for liquid water," Postberg said.

Earth's oceans get their salt from the rocks that enclose them. The same is true of any other body with an ocean. On Enceladus, pressure would push bubbles of ocean spray into space, where they would quickly freeze before they could break apart. These bubbles would become samples of the ocean they escaped.

The geysers of Enceladus are fed by at least one reservoir of water a few hundred feet below the surface. Whether it is a single large lake or several smaller pools is unknown, but in order for the spray to form, a total water-surface area of several hundred square miles must exist.

Geysers from all four tiger stripes are heavy in salt, so the reservoirs must at least be large enough to cover the area under these fissures.

Based on the scientists' study, these reservoirs connect to a larger ocean about 50 miles (80 km) underground. Calculations limit it to the southern hemisphere, but how wide it extends is unknown.

Theoretically, the geysers could be fed directly by a shallow ocean, but geophysicists consider that unlikely because an enormous amount of heat would be needed to keep such a large body from freezing.

The research is detailed in the online June 22 edition of the journal Nature.

Probing for life

Scientists searching for extraterrestrial life have long considered liquid water a primary requirement for its existence, so an ocean under Enceladus' surface provides another potential target.

Postberg pointed out that, unlike other unseen oceans in the solar system, the water on Enceladus is fairly easy to reach. Jupiter's moon Europa, for instance, could have an ocean under a layer of ice, but retrieving it would require significant effort. By contrast, the geysers on Enceladus pull material — and potentially life, should it exist there — from its ocean and shoot it into space.

"The water samples are thrown in front of your spacecraft by the plumes," he said. "You don't have to drill deep to analyze ocean material."

Similarly, as astronomers pinpoint bodies outside the solar system where life might thrive, they tend to focus on planets close to stars, where temperatures are warm enough for liquid water to form at the surface.

But Enceladus, orbiting a planet about 891 million miles (1.4 billion km) from the sun, is cold and frigid on its surface.

"The fact that water is on such a remote and unlikely place surely has implications for the general likelihood of life in the universe," Postberg said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children.