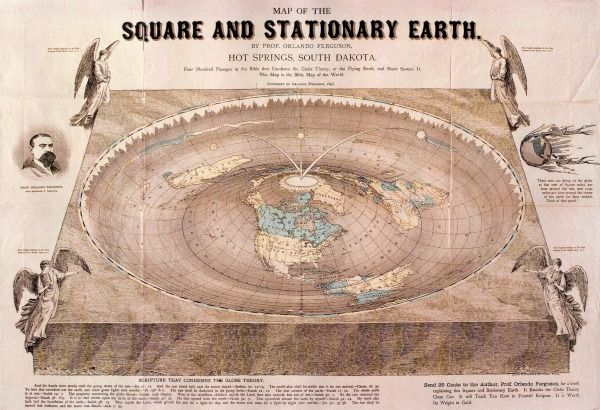

Ingenious 'Flat Earth' Theory Revealed In Old Map

In 1893, Orlando Ferguson, a real estate developer based in South Dakota, drew a map of the Earth that combined biblical and scientific knowledge in a unique way. The map accompanied a 92-page lecture that Ferguson — referring to himself as a "professor" — delivered in town after town, traveling far and wide to share his theory of geography, highlighted by his belief that the Earth was flat.

Ferguson's map represents the Earth as a giant, rectangular slab with a dimpled upper surface. Don Homuth of Salem, Ore., just donated one of two intact copies of the map to the Library of Congress. [See the map]

"It's very fragile. It's printed on tissue paper and hand-colored with watercolors," Homuth said. He got the map from his eighth grade history teacher in Fargo, N.D., who got it from his grandfather, who lived in Hot Springs, S.D. — Ferguson's hometown.

"Now, I'm 67. I don't want it to fall into the hands of relatives, for God's sake! And I don't particularly want to sell it. So we thought we'd send it to the Library of Congress," Homuth told Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience.

The only other copy is housed in the Pioneer Historical Museum in Hot Springs. James Bingham, chairman of the museum's board of directors, told us what he knows about it.

"Ferguson was trying to make an updated version of the flat Earth theory to fit the biblical description of the Earth with known facts," Bingham said. Typical of flat Earths, Ferguson's Earth is a rectangular slab, the four corners of which are each guarded by an angel. "What makes his flat Earth different from other theories is his theory holds that the Earth is imprinted with an 'inverse toroid.'" If you were to take a donut and press it into wet cement and then remove the donut, Bingham explained, the rounded impression it left in the cement would be what is known in mathematics as an inverse toroid.

"It's pretty clever because it explains the Columbus phenomenon, where you see ships coming in over the horizon and gradually the mast gets taller and taller until you can see the ship," Bingham said. "By 1893, most people knew about horizons so he had to come up with some way to explain that."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The map also has a picture of a man holding onto the Earth for dear life, with an inscription that reads: "These men are flying on the globe at a rate of 65,000 miles per hour around the sun, and 1,042 miles per hour around the center of the earth (in their minds). Think of the speed!" Yeah right, Ferguson seems to have been implying. [Read: What's at the Center of the Milky Way?]

"These people truly believed that the Earth is not a globe!" Homuth said. "A lot of stuff like this got ignored and swept into history's wastebasket. But at the time people actually believed this stuff!"

Incredibly, some people still do. The Flat Earth Society is an active organization currently led by a Virginian man named Daniel Shenton. Though Shenton believes in evolution and global warming, he and his hundreds, if not thousands, of followers worldwide also believe that the Earth is a disc that you can fall off of.

"I haven't taken this position just to be difficult," Shenton told The Guardian last year. "To look around, the world does appear to be flat, so I think it is incumbent on others to prove decisively that it isn't. And I don't think that burden of proof has been met yet."

To Mr. Shenton, we offer this NASA/NOAA GOES-13 satellite image of our planet as it looked on March 2, 2010.

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Most Popular