Running and Learning Use Same Brain Waves

What do learning and running have in common? They seem to use the same brain waves.

The pattern of brain waves, called the gamma rhythm, "is known to be controlled by attention and learning, but we find it is also governed by how fast you are running," said Mayank Mehta of the University of California, Los Angeles, a researcher in a new study involving mice. "This research provides an interesting link between the world of learning and the world of speed."

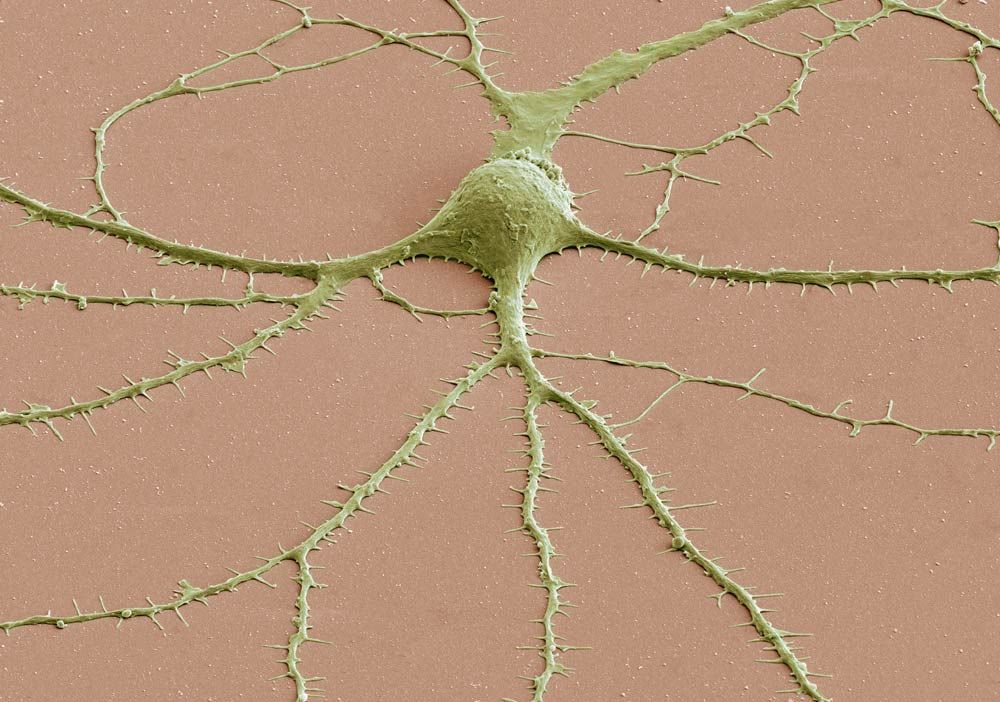

The gamma rhythm comes from the hippocampus, the part of the brain associated with memory during concentration and learning. The hippocampus records facts and events as they happen, holding them until they can be formed into long-term memories during sleep. (Injuries to the hippocampus result in damaged ability to form new memories.)

The researchers studied the brain waves of mice as they ran in the lab. Specific spikes in the brain's electrical activity — one way the brain cells communicate — seemed to show an increase in the gamma rhythm as the mice moved faster.

The researchers don't know how this might influence the learning process in the hippocampus.

"Deciphering the language of the brain is one of the biggest challenges that human beings face," Mehta said.

Learning about how the brain works can help researchers understand how the signals go awry, Mehta said. "If we can learn to interpret these brain oscillations, it may be possible to successfully intervene in cases ranging from learning disorders to post-traumatic stress, or even to mitigate the effects of cognitive decline with aging."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study was published June 24 in PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.