Will Newly Discovered Comet Dazzle or Disappoint in 2013?

A newfound comet discovered by astronomers using a telescope in Hawaii will swing through the inner solar system in 2013, with some astronomers and skywatchers hoping for a cosmic spectacle when it arrives.

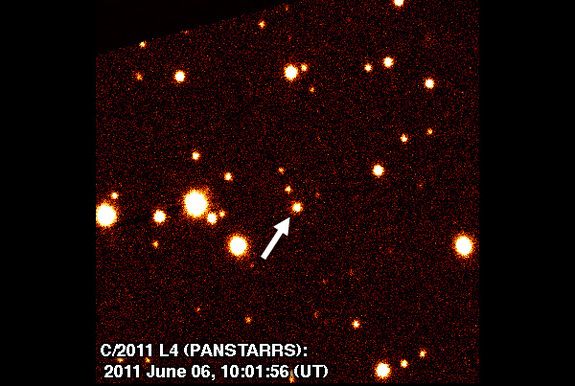

The comet is C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS), an object named after the asteroid-hunting Pan-STARRS 1 telescope that detected the icy wanderer during the overnight hours of June 5 and 6.

Since the comet's discovery, hopes have risen that this "dirty snowball" presently heading sunward from the depths of the solar system could evolve into a memorable sight. Indeed, some forecasters have already suggested that comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) could become the celestial sight of the decade.

But right now, it's just too soon to know if that's the case.

Still a long way off

When it was discovered in the constellation Libra, comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) was a 19th-magnitude object — so faint that only telescopes with sensitive electronic detectors could pick it up — some 759 million miles (1.2 billion kilometers) from the sun. Astronomers measure the brightness of objects in space on a reverse scale; the higher an object's magnitude, the dimmer it appears to observers. [Best Close Encounters of the Comet Kind]

The comet's closest approach to the sun, called its perihelion, will occur on April 17, 2013. At that time, the distance between comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) and the sun will have shrunk to 33.8 million miles (54.3 million km).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such an enormous change in solar distance would cause a typical comet to increase its intrinsic luminosity by about 14 magnitudes. Put another way, it could become about 300,000 times brighter. [Comet Dive-Bombs Sun During Solar Eruption]

Furthermore, the comet's distance from Earth, which was 666 million miles (1.1 billion km) at its discovery, will shrink to 118 million miles (190 million km) at perihelion, meaning it could appear an additional four magnitudes brighter. That would make PANSTARRS a first-magnitude object when it passes closest to the sun some 22 months from now.

But while not wanting to sound like a Gloomy Gus, I think I should point out that a spectacular PANSTARRS show is no guarantee, for three main reasons.

What's the orbit?

At the moment, astronomers are not exactly sure about the details of PANSTARRS' orbit. That's because it is so far out in space and moving very slowly.

Astronomers generally need at least three good positions to determine an orbit, but to get a really good orbit nailed down, they need a lot more than that.

Further, if a comet is very far from Earth — like PANSTARRS — its position relative to the background stars doesn't change very much, and the computed orbit is going to end up being very uncertain.

Initially, orbital computations using just a handful of observations suggested that perihelion for PANSTARRS might come in early February 2013. Since then, nearly two dozen observations have been logged, with the latest orbital calculations pushing the time of perihelion into mid-April. It may yet change again, so stay tuned.

First-timer or old-timer?

So far, all of the orbital data for PANSTARRS point to it being a "new" comet, moving in a parabolic orbit. In other words, it may never have passed near the sun before.

That's bad news, because we believe that such comets might be covered with very volatile materials such as frozen nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. These ices vaporize far from the sun, giving a distant comet a short-lived surge in brightness that can raise very unrealistic expectations.

Those of a certain age may recall comet Cunningham in 1940, comet Kohoutek in 1973 and comet Austin in 1990.

Because it was due around Christmas time, anticipation ran high that Cunningham would resemble the fabled Star of Bethlehem.

For its part, Kohoutek was ballyhooed as potentially the "comet of the century," while one popular astronomy journal promoted Austin's approach with a banner proclaiming "Monster Comet Coming!" on its cover.

All three were huge busts.

I remember as a teenager watching "The Tonight Show," when Johnny Carson joked that astronomers should have known that Kohoutek was going to be a bomb because it was the only comet that ever came with a fuse attached to it.

If, on the other hand, PANSTARRS is making a return loop around the sun, its highly volatile materials have already been shed, and what we’ll see in the months to come is the true underlying level of its activity.

In fairness, I should note that not all new comets evolve into duds. In April 1957, for instance, first-time comet Arend-Roland put on a wonderful show, so there are exceptions.

As I've noted, the precise orbit for PANSTARRS is yet to be determined, so all we can do in the meantime is wait and hope.

Celestial showpiece?

If, for the moment, we take the latest computed orbit for PANSTARRS at face value, then don't expect to see the comet until after it rounds the sun. Prior to that, the comet will be too far south to be visible for most places north of the equator.

And even after perihelion it will still take a couple more weeks to free itself from the glare of the sun. Finally, during the first week of May 2013, the comet should begin to become evident around the break of dawn, rising low above the northeast horizon.

Unfortunately, by then it will likely have faded considerably to third or maybe even fourth magnitude — just a dim naked-eye object that is better seen through binoculars. And if the comet develops any kind of tail at all, it will likely appear greatly foreshortened since it will be pointing almost directly away from the earth. [Astrophotography Telescopes for Beginners]

For all of these reasons, then, I think it would be reckless to declare PANSTARRS as the "celestial spectacle of the decade" this early in its apparition. With the passage of time, along with patience, we’ll eventually get a better handle as to how the comet will truly perform.

If this story has a moral, it may come in the words of the legendary comet expert Fred L. Whipple: "If you must bet, bet on a horse, not a comet!"

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.